Domenico Scarlatti was the sixth child of the famed

opera composer Alessandro Scarlatti. The Italian member of the "big

three" of baroque composers born in the year 1685 (Bach and Händel

being the other two), the junior Scarlatti studied chiefly in Venice,

where he worked for the exiled queen of Poland. He also spent much time

in Rome, where he met and competed against Händel in a keyboard

contest which turned out to be a draw, it being decided that Scarlatti

excelled at the harpsichord, and Händel at the organ.

For the majority of his professional career, he would

work in the service of the Spanish royal family, and it is from this

employment that his more than six hundred single movement exercises

or "sonatas" came into being. These works were most likely

written for the teaching of his pupil, the Infanta Maria Barbara who

would later become the Queen of Spain. There is a famous, humorous legend

about Scarlatti that says that in later life he had grown so obese that

he was unable to execute the cross-hand keyboard technique that he invented

because he was unable to clear his large girth to make the maneuver.

The Scarlatti sonatas are of infinite variety and color,

and of widely contrasting mood and temperament. Any grouping of a dozen

or so of these gems makes for an interesting recital in and of itself.

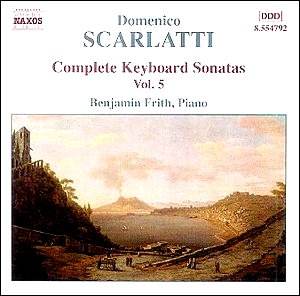

Benjamin Frith dashes off this sampling of sixteen works with tremendous

flair and panache. To the delight of these ears, he does not bog the

music down in displays of "performance practice," nor does

he attempt to make his concert grand sound like anything other than

a modern piano. Yet, he uses pedal sparingly, finds the proper balance

between contrapuntal voices, and brings these brief gems to life with

an infectious grace and elegance.

Frith has ample technique to make the busier passagework

sound easy. More engaging still is the manner in which he handles the

slower, more lyrical works. He knows how to make the piano sing, and

his legato, achieved mostly with the fingers and not the right foot,

is splendid. To sum it up, his playing is effervescent and lyrical,

bringing this music alive in a most enjoyable way.

Keith Anderson provides ample and informative notes,

and the sound quality is superb. A worthy addition to any collection.

Kevin Sutton