SERGE PROKOFIEV

by

Paul ShoemakerIntroduction

Beginnings

Youthful Personality

Early Education

Conservatory

Years of Travel

The Return Home

Epilogue

Summing Up

Afterthought

Recommended Recordings

Acknowledgements

Web Links

ChronologyFifty years after his death in 1953 the music of Prokofiev is more popular than ever. His large catalogue includes 133 completed numbered works with many pieces of juvenilia also known. Because of his excellent technical education received at the St. Petersburg Conservatory from Rimsky-Korsakov and others, his scores present no problems of interpretation in spite of his very personal, even exotic, musical style. His intentions are clear, however difficult they may be to execute.

He showed excellence, innovation and a high degree of individuality in every musical form. Much of the time one can easily identify his music from hearing only a few bars. Yet his catalogue contains many surprises and the range of his expression is wide and deep, reflecting the extraordinary extent of his genius.

Like many composers, he expressed great humanitarian spirit through his music. In person he was rude, irascible, infantile, capable of devastating insults. Those who could accept love on his terms remained his friends, or, at least, allies; but he made many enemies. Then during his very last years he suddenly became a "nice guy," kind, courteous, considerate, supportive. He had always loved playing for children and was said to have a special ability to communicate with them.

Prokofiev left Russia in 1918 and returned in 1936; he viewed the eighteen years he spent living outside Russia as an isolated episode. He considered himself a true Russian composer. This is in contrast to Stravinsky, Glazunov and Rachmaninoff who left Russia at about the same time and for some of the same reasons, but returned only on brief visits. Having travelled more than most composers and having gone completely around the world, he eventually went home and stayed there for the last 17 years of his life.

Sergey Sergeyevich Prokofiev was born at 5.00 in the afternoon in Sontsovka (now Krasnoje), Ukraine, on April 23, 1891 (New Style; the date in the Ďold styleí [Julian] calendar then in effect was April 11). Sontsovka/Krasnoje with a population of 1000 (1950) is too small to show on most maps and is about 130 km north of Zdanov, a port city on the Black Sea. The nearest train station is at Krasnoarmeyski a 25 km carriage ride away. The largest building in town is and was the church. The village has put up a statue and several plaques in honour of its most famous native son. The land is flat, barely rolling, with few trees but many colourful flowers in the Spring. As a result the sky, its clouds and mysteries loomed very large, its lights very bright during the dark nights.

His fatherís family were small property owners, his motherís family were originally serfs. Sergey Alekseyevich Prokofiev was an agricultural scientist employed by the local landowner, Sontsov, to improve the productivity of his estate. Maria Grigoryevna Prokofieva (née Zhitkova) was a skilled amateur pianist and particularly enjoyed playing the early Beethoven piano sonatas, the works of Chopin and of Anton Rubinstein whom she considered to be a much better composer than Tchaikovsky. "Mozart effect" or no, the infant Prokofiev went to sleep many nights hearing his motherís piano playing. He had his first piano lessons at age four, and was writing music by age five; all of these pieces were written down and saved in a decorative notebook. He had absolute pitch and could name any note he heard played, or play any note he heard.

His two sisters had died very young and Prokofiev was therefore an only child. His father taught him mathematics and science; his mother taught him arts and letters, being careful to allow his natural curiosity to set the pace of the lessons. She included Bible lessons because such knowledge was then still considered the basis of a liberal arts education. Governesses taught him French and German. Although his father was an Atheist, he believed religion was good for the people and attended church on important religious holidays with his family as part of his community responsibilities. By the age of 10 Prokofiev was already quite a good chess player and he maintained his enthusiasm for chess throughout his life. His parents were politically progressive but not radical; they put a great deal of time and effort into improving the education available to the agricultural workers in Sontsovka.

We can have no exact way of knowing what this shy, quiet child was thinking. A clue to his mental state comes from the only fairy tale he composed himself, Peter and the Wolf. He put some of his finest and most personal music into this composition, and was deeply gratified by the favourable reaction of his public. Like Prokofiev, Peter is a bright boy who lives in the country. He has no friends, no brothers or sisters, and no parents! But we know that Prokofiev had a responsible father and devoted, doting mother who encouraged his musical studies. But it is possible under these circumstances to still feel utterly alone in the world. In Peterís world, his only family is his grandfather who has no function beyond warning him not to go beyond the bounds of conventionality, something Peter and Prokofiev did at once without a secondís hesitation.

Peter is not completely alone; he has imaginary friends: animals that talk. Nature is beautiful and musical. Then, Evil comes into his world, from Nature, or from nowhere in particular. Peter and his imaginary friends just barely manage to save the situation when they are rescued ó not by family or friends, certainly not by Jesus, but by a force of good that comes from nowhere in particular, some hunters wandering by. And, with everything settled, Peter is then free to go on with his adventures with his imaginary friends. (I agree with the Disney artists that the final joyful instrumental flourish depicts the duck escaping alive from the wolfís stomach; otherwise it would not be so happy an ending.)

Prokofiev also set other, more traditional, fairy tales in music. In Romeo and Juliet we have more people who defy convention and go beyond it and are very happy about that. Then Romeo makes the mistake of doing the conventional thing, avenging a slain kinsman, and everything falls apart. Prokofiev also set The Ugly Duckling and Cinderella, favourite stories of lonely children, where family and friends do nothing but cause pain, and rescue and eventually glory comes from powerful forces outside. Some versions of Ugly Duckling are quite mild. Russian fairy tales are often very bloody; Prokofiev set the Western version of Cinderella. But in Prokofievís Ugly Duckling, written when he was 23, the duckling nearly freezes to death in the Winter after being driven away by the duck family. In the Spring when he sees the swans coming toward him he expects them to kill him. If this reflects Prokofievís personal childhood anxieties, they were very deep indeed.

Living in a flat country with little vegetation, as Prokofiev did, he knew as I know that the horizon is false. It is no boundary, but rather a perpetual lure, a constant reminder that there is another space just beyond. Prokofiev in observing nature was well aware of another fact of living in a very cold dry climate: for a number of months of the year, hydrogen oxide is a mineral. Snow is like sand; it doesnít melt although it can evaporate. Ice is like glass, and it is beautiful in its many sparkling forms. Russian music has always been full of sparkle, depicting ice crystals as well as the stars. Ice is beautiful, but it is deadly; it is hard and sharp and can cut you, it is cold and can suck the life out of you. Prokofiev himself described the sometimes cruel brilliance in his music as "steel" but it could just as well have been ice. But ice or steel there was a hardness under the soft surface in all of Prokofievís music. It might be a clocklike andante rhythm (from Haydn?), a pulsing bass drum, a bitter chord, or the hard glitter of percussion. In Romeo and Juliet at the peak moment of passion when the loversí warm bodies are pressed together for the last time, Prokofiev introduces the military snare drum (and the bass drum) into the orchestral texture. Is this just a reminder that Romeo and Juliet is at heart an anti-war story, or does it represent the cruel inexorability of fate? Or is this also the brittleness that Prokofiev finds inseparable from beauty?

Throughout his career, Prokofiev never wrote a single note of religious music, this in sharp contrast to his teacher Rimsky-Korsakov who was a composer of the Tsarís royal chapel, and Stravinsky, his older colleague, who remained a professing Catholic throughout his life. During his conservatory studies, an attempt was made by his family in St. Petersburg to get him to go to church, but with no success.

He was eight years old when his mother felt the time had come to take him by carriage and train to Moscow. His first experience in the theatre was a performance of Gounodís Faust and it moved him profoundly. This was followed by Borodinís Prince Igor, and by Tchaikovskyís Sleeping Beauty ballet at the Bolshoi. He had been writing piano pieces since he was five, but upon his return from the first trip to Moscow he immediately wrote an opera "The Giant" the score of which was bound elaborately and kept on the piano. The following year he was taken to Moscow again and then to St. Petersburg for more opera and ballet. His mother obtained an audition with Sergey Taneyev, pupil and friend of Tchaikovsky and Director of the Moscow Conservatory. Taneyev agreed that advanced lessons should begin at once and arranged to have the 28 year old Reinhold GliŤre spend Summers at Sontsovka giving private lessons in composition to ĎSeryozha.í Taneyev remained an interested friend and wanted to receive regular reports on Prokofievís progress.

GliŤre was an excellent teacher and became a family friend. In the evenings Prokofiev would accompany him on the piano while Glière played the violin in Mozart violin and piano sonatas. Prokofievís mother who taught piano in Sontsovka learned much about music instruction from GliŤre. She never tried to interfere in his lessons for which he was grateful. But even though GliŤre taught Prokofiev in detail how to construct each kind of sonata movement, how to lay out large works, even elementary orchestration, we donít hear GliŤreís music in Prokofievís music, other than the love of large forms and large orchestras. Prokofiev always knew what he wanted to say and was impatient to get to saying it. He was grateful for knowledge of how, but needed no teaching of what.

During these years Prokofiev was "at school" virtually every waking moment. He had lessons from his mother, lessons from his father, lessons from GliŤre, either in person or as exercises through the mail. If he had any spare time he played Ď21í with the chamber maid ó in French or German. While he occasionally referred to his piano pieces as "little dogs", he also had two real puppies, Shango (Named after the Nigerian God of Fire and Thunder) and Bobrik (Ukrainian for castor, originally an odorous medicinal substance extracted from the glands of beavers. Puppy Bobrik must have had a bad smell!); Shango had chronic ear infections and required medication and treatment. Prokofiev was cranky much of the time, complaining that what he really wanted to do was write operas and symphonies, whereas he was constantly being admonished to do his exercises first. He wanted to explore music, so he would play as many piano pieces as possible without learning any one of them well, and was scolded for that, too.

Eventually the question of Prokofievís education reached a new level. There were no adequate high schools locally; Moscow and St. Petersburg were each a two-day journey away. Eventually, after much argument and many tears, it was agreed that Prokofiev and his mother would move to St. Petersburg, at least for the Winter, and Father would join them there whenever he could. Sonstov generously agreed to allow him to absent himself from his duties frequently. Everybody would be together in Sontsovka in the Summer. After many trips back and forth and lessons of varying degrees of success, it was agreed that Prokofiev would enter the Conservatory and take his high school classes there. But this quickly proved unworkable because of the time required for music courses. It was decided that all non-music classes at the Conservatory were to be cancelled and Prokofiev went back to being home schooled by his parents in the evenings and on weekends. Prokofievís father asked Prokofiev to approach one of the students in the academic curriculum and ask him to make a list of the subjects being discussed, for which he was to be rewarded by regular gifts of boxes of chocolate. That way Prokofievís education could be kept up with his contemporaries.

For the first time in his life he met boys his own age with similar interests, and quickly established lifelong friendship with Miaskovsky. Some other friends were judged "unsuitable" and it was demanded of him that he stop seeing them, and he obeyed. But Prokofiev had no social skills; he was rude, presuming, naive, disrespectful, and tended to blow up if things did not go his way. He retained this personality of the spoiled bright child for many years to come, and it was to cause him much grief and many setbacks and to make attaining his true recognition much more difficult.

The 1905 uprising caused disruption in daily life and some fears, but things quickly went back to "normal," except that Rimsky-Korsakov had been expelled from the Conservatory for siding with the activists. But next year he was readmitted and everything seemed fine for the time being. It seems unbelievable to us today that the events to come cast no more shadow before them. Middle class life in Russia was orderly and prosperous and even progressive people seemed to feel that serious problems could be avoided.

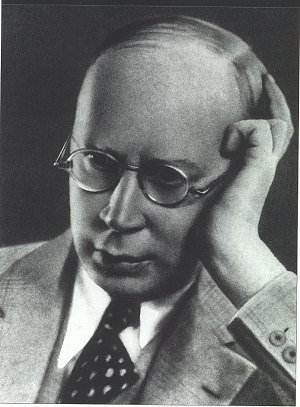

Prokofiev had an unusual physical appearance, with a long face, eyes set close, with very prominent lips and forward chin and mouth, this from his motherís side of the family. (He was occasionally referred to as a ĎWhite Africaní) Pianistic success was facilitated by his enormously long fingers. Because of his shyness he did not smile much in public, but when he did, as in his wedding picture, his face was transformed with an embarrassed broad grin. During his early years his face was immobile in an expression of bright curiosity which many chose to interpret as conceit or contempt, and reacted accordingly. He was condescending towards inferiors and refused to show deference to notables. He took a special delight in watching quarrels in the street, even peeking through windows, which has been excused as being a natural expression of his theatrical instincts. By his late 30s his brow had taken on a permanent furrow and his habitual expression from then on always held a trace of a frown. At this time also he took to wearing small wire frame glasses, similar to his fatherís. His whole life long he was accused of being spoilt and accustomed to privilege.

Rimsky-Korsakov was concerned that Russia did not need any more talented musical amateurs like Mussorgsky, Russia needed musical technocrats. Thus Prokofiev received a rigorous musical education at the St. Petersburg conservatory and his early works are perfectly constructed. Like Wagner, and unlike Beethoven, Prokofiev simply wrote out his music, and that was that. Only one major work was ever subjected to serious revision (the Fourth Symphony), and that very late in his life. On the other hand, he was not unwilling to make changes in his music to suite the intended purpose. He would write his film music so it could easily be edited to fit the filmed action, and was hence a valued collaborator. He added a cheerful coda to the Seventh Symphony in response to criticism that the work ended on too depressing a note.

His teachers were Liadov (composition, harmony, counterpoint), Tcherepnin (conducting), and Alexander Winkler (piano). Orchestration was taught by Rimsky-Korsakov, who was also Administrator of the Conservatory, and Prokofiev openly, tactlessly, criticised his methods. Prokofiev also alienated Glazunov, who was later to be Shostakovichís teacher, such that Glazunov opposed him at times and had to be pushed out on stage to announce Prokofievís winning of the Rubinstein Prize in piano.

For all his at times exotic orchestral sound, his scores look surprisingly ordinary and easy to read, for he achieved his brilliant effects using very simple, direct, and ingenious means. At times he would write his works Ďoní C major, that is without key signature, and just add the accidentals as necessary without bothering to notate elaborate changes of key.

The question of the influence of Russian folk music on his compositions is complex. Prokofiev was certainly no man of the people. He was the son of an employee of the local landowner; the peasant boys he played rough and tumble with were required to address him in the formal second person while he addressed them in the familiar second person form. His idol Tchaikovsky, his teachers GliŤre and Rimsky-Korsakov and his elder colleague Stravinsky all made very extensive use of folk-tunes and quotations in their music, whereas only Prokofievís second string quartet can be shown to make direct use of such material. His music sounds nothing like that of his closest associates, Miaskovsky and GliŤre, nor like that of his composition teacher Liadov. However it is claimed that, like Bartók, Prokofiev was fascinated by certain harmonic and rhythmic aspects of the very oldest folk materials. Examples can currently be found in Bulgarian womenís ensembles today but at the time of Prokofievís birth were probably to be heard in his home town. These musical qualities could have formed a basis for his austere, astringent harmonic and rhythmic style. A Russian friend says she can hear the "Russianness" in all of Prokofievís music, but none of it in, say, late Stravinsky.

Also in this regard there is a story in Prokofievís diary that deserves to be quoted: In 1902 Prokofiev visited Taneyev and they played on the piano Prokofievís newly finished student symphony. Ď... Taneyev said, "Bravo! Bravo! But the harmonic treatment is a bit simple. Mostly just ... heh, heh ... I, IV, and V progressions." That little "heh, heh" played a very great role in my musical development. It went deep, stung me, and put down roots. When I got home I broke into tears and began to rack my brains trying to think up harmonic complexities .... An eleven-year old boy had visited a professor; he had remembered some of his comments and paid no heed to others ... Only four years later my harmonic inventions were attracting attention. ... eight years later [when] I played one of my most recent compositions for Taneyev, he muttered, "It seems to have a lot of false notes. ..." At this I reminded him of his "heh, heh." He put both hands to his head and exclaimed not without humour, "So I was the one to nudge you onto such a slippery path!"...í [tr. Guy Daniels]

When Prokofiev set off across Siberia to fulfil a concert engagement in New York he expected to be back in Russia within the year. Even though his train was stopped several times due to military engagements he, along with many others, seriously underestimated the extent of the civil war then in progress. In New York he was greeted warmly by the émigré community and his concerts went very well. He met Carolina (Lina to her friends) Ivanovna Llubera Codina; it had taken her some time to get up the nerve to approach him, but as soon as he saw her he knew he wanted to see her again. She had been born in Spain, but her mother was Polish and Alsatian. Lina spoke several languages including a little Russian, dressed very stylishly, and had friends in many countries. She was very beautiful and just beginning her career as a singer. Over the next years he would see her more and more frequently in the US and in Europe as their friendship slowly ripened into love.

Prokofiev had always been generally very healthy, but in New York in 1919 he fell ill with scarlet fever, which developed into diptheria. He recovered quickly and continued with his very busy schedule.

Over the next years he travelled frequently back and forth to Europe frequently arranging concerts and premiering new works. He encountered Lina frequently as she pursued her operatic career. People continued to leave Russia for France, including many of his friends who brought his manuscripts with them. His mother had endured serious hardships during her escape from Russia via Constantinople and eventually arrived in Paris, never to regain her robust health. About this time it was discovered that Lina was pregnant, so Prokofiev and Lina were married. They had settled with Prokofievís mother in Paris by the time their first son Sviatoslav was born in February of 1924. Mother approved of his marriage to Lina and enjoyed living in their Paris household with her grandson briefly before her death in December of 1924 at the age of 68. Even though Prokofiev and his fiancée did not marry until after she became pregnant, he clearly wanted children, and was a devoted father committed to giving his children the best he could. He spent much time playing with them even though the responsibilities of being head of the household required many concert engagements to earn enough money.

He reportedly carried with him two notebooks in which he wrote down musical ideas as they occurred to him. When someone would approach him to offer a commission, during the fee negotiations, Prokofiev would teasingly say, "Shall I write from the red notebook, or from the blue notebook?" Clearly, if offered a little more money, he could try a little harder. For all of his naive personal manner, he was shrewd and determined in fee negotiation.

After his initial successful concerts, the USA offered Prokofiev good money, but also argument and unpleasantness; he thought American audiences boorish and unsophisticated. European audiences and impresarios were better able to cope with his autocratic personality. Diaghilev knew how to manipulate his two "sons" (Stravinsky and Prokofiev) and was able to coax excellent works from them and maintain a good working relationship, resulting in success all around.

The death of Diaghilev and Prokofievís legendary quarrel with Diaghilevís successor Balanchine over the Prodigal Son ballet cut him off from the ballet world. Balanchine called him a "bastard" and Prokofiev called Balanchine Ď... nothing but a lousy ballet master ...í and dismissed him contemptuously. The quarrel ran deep and strong. In severing him from the ballet world it also severed him from what had a good source of income. Then his mother died. Koussevitzky and many others moved to the USA. He declined to join them. Prokofievís roots in the Paris seemed to be being cut off one by one.

During Prokofievís composition training the model works used by his teachers as the basis for musical analysis had mostly been Beethoven, to a lesser extent Mozart and Haydn. His early successes in Paris had been with colourful music more or less intended to startle and shock, and the audiences seemed to love it. In his 2nd symphony he attempted a complex development of his style, a theme and variations movement based on the model of Beethovenís Hammerklavier Sonata. In this he thought to move toward a more mature and sophisticated architectural style. But audiences and critics alike failed to appreciate the work.

The failure of this work shook him very deeply; he took it as a warning not to move further in this direction. Even more significant to him was the workís more sympathetic reception following a performance in Russia. Thereafter Prokofiev tended to interpret every success in the West as proof of his skill as a composer, every disappointment as proof that the Western audiences did not understand him. Every bit of good news from Russia pleased him profoundly, whereas bad news from Russia he tended to dismiss. Inexorably, everything that happened became one more step toward returning to Russia.

Gradually American audiences came to appreciate his music and European music in general. Many other European musicians were to move to the USA in the following years and establish émigré colonies in New York and Hollywood. But Prokofiev was unaffected by this trend, and continued to feel himself drawn back to Russia.

Written just before the final move to Russia, the Romeo and Juliet ballet is probably his greatest single work, one which clearly shows his "new" romantic, lyrical style. A number of dances in the work could easily have been constructed by Haydn or Beethoven; but the great melody at the tomb scene can have come from no other source than the keening wail of peasants of the steppes. In the Cinderella ballet Prokofiev showed a greater debt to Tchaikovsky; but here the "clock scene" makes clear a debt to Haydnís "Clock" Symphony.

Prokofiev was so sure of his genius that he did not take seriously suggestions that in Russia he would have difficulties with censorship and official disapproval, even though he was clearly warned. During his visits there he had had arguments with officials, and with his usual lack of tact insulted them, steadily making enemies, yet he dismissed advice from friends that he was setting the stage for trouble. Since Shostakovich had not yet become so well known in the West, it has been suggested that Prokofiev may have thought he would be so obviously the very greatest composer living in Russia that everyone would have to admit that and pander to him, as people always had. Circumstances must have shown him the error in this line of thinking, but once established on his path he seemed unable to deviate from the course he had set for himself.

At first he seemed secure in his status in Russia and felt welcome and appreciated. But once his Paris household had been dissolved and he and his family were irrevocably situated in Russia things rapidly went from bad to worse. The 1938 attack on Shostakovich, clearly intended to be a warning to all Soviet composers, began to affect his popularity as well. Some new compositions were bluntly rejected, scheduled performances of established works were cancelled. Some of this was official ideological oppression, some of it was just the anger and resentment of insulted musical bureaucrats who used their power to teach him a lesson and control the loyalties of others. A far more serious and general attack occurred in 1948.

Prokofievís error was in assuming that these declarations were true invitations to serious discussion (they explicitly included the phrase "comradely dialogue"), a real trial in which he could defend himself and be vindicated. But it is probably true that they were simply elaborately staged public pageants. The record shows that Prokofiev wrote two lengthy and detailed confessions to the charges, but it is also suggested that these documents were prepared by the authors of the original declarations and that there was in fact nothing for the affected composers to do but watch and listen and hope to survive. For instance, Shostakovich insists he never wrote or said "A Soviet artistís reply to just criticism" in regard to his 5th symphony. Since that was the only acceptable reply, it was made for him to save him from a false step. On other occasions it is reported that typed out speeches of confession were pressed into the hands of the miscreants as they were ordered forward to reply to their denunciations. In one sense there was no ambiguity: music students were being told in the most direct terms possible that they were not to imitate Prokofiev, or death could be the result. Had it become necessary to kill Prokofiev, for instance, to make this lesson clearer, there would have been nothing he could have said, no act he could have performed which would have prevented it. Prokofiev lived because it did not become necessary to kill him, and for no other reason.

Prokofiev had many happy memories of Summer visits to Kislovodsk in the Caucasus Mountains with his mother. In 1939 the strain in Prokofievís marriage must have reached a critical level as Prokofiev summered in Kislovodsk alone while Lina was elsewhere and the boys were in summer camp. In Kislovodsk he met Maria-Cecelia (Mira) Abramovna Mendelson, and quickly began to be friendly with her. She was apparently a distant relation of Stalinís and some have suggested she was planted to spy on him, or to break up deliberately his marriage to the suspected Lina, or that she was able to intercede on his behalf with Stalin. No credible evidence of any of these suggestions has been discovered. But as a Soviet citizen and lifelong resident, Mira was able to counsel and advise Prokofiev on Soviet internal politics and helped him avoid even worse trouble with the authorities. After their return to Moscow, Prokofiev and Mira continued to meet discreetly. In 1941 Prokofiev finally left his family and moved in with Mira at her parentsí house until they could be granted their own apartment. Prokofiev continued to provide financially for Lina and the boys.

In 1944 at a rest home in Ivanovo, Prokofiev adopted a stray dog (possibly a Malamute) whom he named Zmeika ("Little Dragon"). After dinner each evening he would walk among the tables and collect scraps for the dog, who became a loyal friend and followed him everywhere. When the dog was run over, Prokofiev was very depressed.

In January of 1945 Prokofiev had a dizzy spell which was probably a heart attack and fell in his apartment, sustaining a concussion. He was rushed to the hospital where severe hypertension was diagnosed. For the eight years remaining in his life his health would vary in its degree of weakness. He would be in and out of hospitals, occasionally travelling to restful locations in the country. He kept to a light work schedule by his doctors. But his low spirits could only be mediated by work, and he continued to compose as much as he possibly could. Some of his finest works remained to be written.

With Prokofiev ill and dodging brickbats from officialdom, and living with his mistress apart from his wife, Prokofievís enemies saw a chance to do some real damage. One must never underestimate the hatred that ordinary talent has for true genius. Although the opera, movie, and the plays exaggerate (and perhaps falsify) this situation in the case of Mozart and Salieri there are other examples in history. The absurd neglect of the magnificent music of Sir Donald Francis Tovey is clearly due to resentment against him for his genius, for his critical bluntness and rudeness; evidently passed down from teacher to student, the otherwise inexplicable anti-Tovey sentiment is still strong in the UK. Geniuses can make things hard on themselves because often they cannot believe that what is so easy for them is impossible for others; they tend to dismiss the less talented as stupid and/or lazy. Soviet Russia provided many opportunities for the slightly talented to gain power and punish genius, sometimes for their own gain, sometimes for their own entertainment. Tikhon Krennikov and Dmitri Kabalevsky are two modestly talented composers who are known to have intrigued against the Prokofievs.

It was 1948 before Prokofievís first marriage was dissolved and he married Mira. In some ways the two Mrs. Prokofievs could hardly be more unlike. Lina was Spanish, sophisticated, at home anywhere in Europe, always dressed fashionably. Mira was Ukrainian, Jewish, had lived all her life in the USSR and had never known "nice" clothes. Lina was an opera singer with her own independent career, while Mira was not very musical. But in both cases the courtships were very long; friendship developed long before passion. But both women were helpmates and valuable advisors: Prokofiev needed Lina to help him get along in sophisticated European society. He needed Mira to help him function in Soviet society. He could accept this kind of advice from women but not from men.

Lina Prokofieva no doubt assumed that as a Spanish citizen with many friends in the West and at the Western embassies, she was safe from official disapproval, but in fact the opposite was true: she was considered all the more dangerous. On February 20, 1948, Lina was arrested by the State Security Police. There seems little doubt that some evidence against her was falsified and that at least some of the officials involved sincerely believed that she was guilty of spying. Many friends tried to help her with no result, and Prokofiev eventually warned people not to be too open in their support lest they be arrested, too ó lest he be arrested, too. Even though she was convicted of spying and sentenced to 20 years, Lina was treated better than many. Her sons regularly sent her food packages and eventually were allowed to visit her. After the death of Stalin, she was offered release if she would confess, which she refused to do. She was assigned light work duty, eventually released and allowed to leave the USSR, and lived to a reasonable old age, indicating that her health had not been severely compromised. Once outside Russia, she became heir to back royalties on Prokofievís music performed in the West and was financially secure. Prokofiev always believed himself partly responsible for her suffering and the strain on him damaged his health and shortened his life, but Lina never blamed her husband and to the last she was a champion for the furtherance of his art and reputation.

In his later years of poor health he was criticised for writing out his orchestral music (e.g., the 7th symphony) in piano score format with annotations and leaving the preparation of the orchestral score to associates. Naturally nothing was put down that the composer did not approve of, and he was thus able to write more music particularly at times when his health limited his energy. His personal orchestral sound is strongly identifiable, so the charge that others orchestrated his music for him is obviously unfair. Other composers (e.g. Bartók) have done the same thing in varying degrees. In todayís world of commercial music it is frequently the case that composer and orchestrator perform completely separate functions and often they donít meet.

With Prokofiev demonstrating such extreme stubbornness, one thing becomes clear: those who say his Russian music was dictated by commissars are obviously off the mark. Whatever else happened in Russia, Prokofiev wrote exactly what he wanted to write. His change in style to a more lyrical less astringent style was something he wanted, something that had been in process for some time before his moving to Russia, as witness the Romeo and Juliet ballet and 2nd violin concerto, both written before, or perhaps during, the move. However a question may yet remain regarding a piece such as On Guard for Peace written when Prokofiev was ill and frightened and in need of money; it won him a second class Stalin Prize. The work is almost never played today. But Valery Gergievís recent recording of the opera Semyon Kotko shows that even when he was attempting to please the commissars, Prokofiev was never less than brilliant. There is probably much magnificent music buried behind these unpromising titles, and it is to our benefit to explore it. Is the situation so very different from the pre-Renaissance when the Catholic Church was the only music patron and everything written was either an Ave Maria or a Te Deum or a Mass of some kind? If persons of strong religious preferences refuse to listen to this music on sectarian grounds they are cutting themselves off from much beauty.

On the evening of March 5, 1953, Prokofiev was in his study at home working on revisions to the Stone Flower ballet, then in rehearsal at the Bolshoi. He and Mira had several visitors. At 8 p.m. he had a severe dizzy spell accompanied by head pain, nausea, and fever. The doctor was called, he was medicated; but by 9 p.m. his breath had failed and he was dead. He was just short of 62 years old. Stalin died of the same cause just 50 minutes later.

In respect of Prokofievís Atheism, a completely civil, non-religious funeral service was held. David Oistrakh played the first and last movements of the f minor Violin Sonata, and Samuel Feinberg played Bach. A pine bough was laid on the coffin, as flowers were impossible to find in Moscow due to Stalinís funeral the same day. Prokofiev rests in the Novodovichy cemetery in Moscow. His second wife Mira died in 1968 and rests beside him there. His first wife Lina was released from prison in 1956; in 1974 she was she allowed to leave the USSR, reclaimed her Spanish citizenship, and moved to London. Lina died in London in 1989 and is buried next to Prokofievís mother in Paris. Prokofievís eldest son Sviatoslav became an architect in Moscow, moving to Paris in 1992 with his wife and son, Serge, and his wife and family. Prokofievís second son Oleg became an artist living in London, where he also helped translate and publish his fatherís diaries.

Despite Prokofievís enormous popularity at times during his life, some of his major works were never performed during his lifetime. He had continued composing during times of disappointment and neglect, as working with music was the only drug which could ease his pain. War and Peace in the complete 13 scene version was finally performed only in 1957, The Fiery Angel was first performed in France in 1956. Semyon Kotko was staged successfully in Russia in 1970. The Cantata for the 20th Anniversary of the October Revolution was not performed anywhere until 1966!

His complete works were published in Russia in 1955.

Prokofiev was a musically talented child and received an excellent musical education. He worked hard all his life and was generally appreciated, although his determinedly individual musical style and aloof, even rude and arrogant, personal manner did not contribute to his popularity and led to personal and professional misunderstandings. He was a performing concert pianist for a time and premiered most of his own early works. In later years the cream of Russian artists competed for the privilege of playing his new music in public.

He married twice, fathered 2 sons, had virtually no personal friends, and was not directly influenced by any other living musician; his earliest teachers were startled by his originality.

Prokofiev wrote works in every form, and his major works today are available in recordings by the foremost artists of the age attesting to his rank as one of the very greatest composers of our time. His flute sonata, Op 94 is one of the anchors of the flute repertoire, and his piano sonatas rank among the finest, and also among the most difficult. His great romantic ballets rank with those of Tchaikovsky. He was a true child of the 20th century in that two of his very greatest works were film scores. Widely played as concert suites, these works have dignified the form. His score for the Eisenstein film Alexander Nevsky has contributed to making that film one of the dozen great classic films of all time. His musical fairy tale for children Peter and the Wolf remains enormously popular and was made into a film by Disney. His seven operas have never matched the popularity of his other works. He had great difficult arranging performances, and only recently are they attaining the attention they deserve. During his life Prokofiev despaired of hearing them performed and reused the music in other instrumental works.

Prokofiev did not take composition students, he never held a teaching post, his children did not become musicians. He did not found a "school." His efforts to simplify musical notation did not accomplish anything. Even though he was at times personally abrasive, he is remembered kindly by virtually everyone who knew him. Almost immediately upon his death official opposition to his music dissipated and he was officially greatly honoured in Russia, which attitude has continued to the present day. He has generally been considered less popular than Shostakovich and somewhat more limited in style, but these two names stand at the pinnacle of 20th century Russian music, if we consider, as most do, that Stravinsky and Rachmaninoff ceased to be ĎRussianí composers when they took up residence in the USA.

AFTERTHOUGHT

About 1960 I had a chance to see Tikhon Khrennikov, who helped lead the 1948 attacks, in action up close. An international music festival was held in Los Angeles to which composers from many countries were invited, including Stravinsky and Milhaud, to present their own music. In addition to the concerts a panel discussion was held to discuss the state of classical music in the world today and in the future. Blas Galindo represented Mexico, Lukas Foss and Elinor Remick Warren represented the U.S, and Khrennikov the USSR. Iain Hamilton, the British representative, opened the proceeedings by delivering an eloquent, stinging attack on any and all censorship of the arts, and Khrenikov applauded him. When it was Khrennikovís turn he began, speaking through an interpreter, by flattering the audience for their taste and committment to music. Then he spoke passionately about the lamentable lack of a major broadcasting symphony orchestra in the US, and was applauded enthusiastically. He continued in this vein saying things the audience would agree with and soon had the audience cheering, applauding, and laughing exactly on cue even though they couldnít understand a word he said. By then he could have said anything at all and they would have gone along with him. He showed himself to be a master crowd manipulator and mass hypnotist. Of course by then the audience knew something else; weíd all heard him conduct his first symphony the night before and we knew he was not a musician to compare with Prokofiev.

Prokofievís catalogue includes 7 Symphonies, 5 Piano concertos, 2 violin concertos, symphonie-concertante for cello, 2 String Quartets, 1 flute sonata, 2 sonatas for violin and 1 for cello, 9 completed piano sonatas, 7 operas, 5 major ballets, 8 film scores, and many miscellaneous works.

A basic library of Prokofievís music should include the following works which will afford much pleasure in repeated listening:

Symphony #1, the "Classical"

Symphony #5

Romeo and Juliet ballet (complete, or as a suite of excerpts)

Suite from the opera "The Love of Three Oranges."

Piano Concerto #3

Violin Concerto #2

Flute Sonata Op 94 (the same music is also played as Violin Sonata #2, Op 94a)

Piano sonata #7

Alexander Nevsky: Cantata based on the film score, Op 78

I recommend that one simply purchase those CDs available easily at a favourable price, or choose versions by oneís favourite artists. For instance, my favourite recordings of Symphonies 1 and 7 are on an EMI Classics for Pleasure issue #CD-CFP 4523 (one critic recently nominated this recording for reissue in the GROTC list), and my favourite Symphony #6 is on Naxos 8.553069. The choice of Heifetz or Perlman on Violin Concerto #2 is entirely a matter of personal preference. Every recording of the Fifth Symphony I have heard seems to fail to reach clear to the heart of the music, which is probably not the fault of the performers; conductors who concentrate on playing the notes and avoid gushing (e.g., Dorati, Szell, Sargent and Reiner) tend to be more successful. Stokowskiís recording of the Fifth Symphony is disappointing, but Stokowskiís recordings of the ballet music excerpts are quite good. Digital sound is especially favourable to Prokofiev due to his extensive use of high and low percussion, sharp dynamic contrasts, and frequent thick orchestral textures.

The following short list of exceptional recordings will not constitute a representative overview of his úuvre:

The first violin sonata in f, Op 80, is recorded with hair-raising intensity by Wanda Wilkomirska and Anne Schein on a Connoisseur Society recording, CD 4079. This recording is currently out of print but I have the personal assurances of the owner that it will be shortly restored to the catalogue. This recording is a must-have for any Prokofiev enthusiast and is worth any difficulty to obtain. It should carry a warning label: do not listen with the lights off.

Bella Davidovich recorded piano arrangements of dances from the Romeo and Juliet ballet on a Philips disk 412-742-2 which also includes the 3rd piano sonata and some Scriabin works. The better you know this music in its orchestral form the more you will be amazed and delighted by Ms. Davidovichís (and Prokofievís) abilities.

Barbara Nissman has very capably recorded the complete piano works on CDs which are remarkable for the completeness of their annotation. Every major section of each movement is indexed greatly facilitating a careful study of the music.

The Peter and the Wolf "Suite" (that is the music without the narration) is recorded by Stokowski on an Everest disk EVC 9048. In this form the music is more readily appreciated by adults who may have grown up with the narrated version but are now naturally put off by its ickiness. The Disney version is available on video as part of "Make Mine Music."

The Romeo and Juliet ballet was filmed out of doors in Russia in 1954 starring Galina Ulanova and Yuri Zhdanov dancing with the Bolshoi Ballet and with Gennadi Rozhdestvensky conducting. This beautiful film is tremendously moving in spite of dated sound and picture quality. Nearly 50 minutes of music is cut from this version, but the core of the drama is intact. Available from several sources on VHS and Laserdisc.

The Prodigal Son ballet starring Mikhail Baryshnikov with the New York City Ballet is available on VHS in Volume 4 of "The Balanchine Library" on Nonesuch 40179-3 (NTSC).

The Japanese music synthesiser artist Tomita produced an interesting electronic pasticcio from a number of pieces of Prokofievís music in his LP album "Bermuda Triangle" not yet released on CD.

Most of the information in this essay has come from Sergei Prokofiev by Harlow Robinson (1987). Prokofievís memoirs, in the form of Prokofiev by Prokofiev, translated by Guy Daniels and edited by David H. Appel (1979), have proven indispensable for the early years. Sergei Prokofiev, Soviet Diary 1927 and Other Writings, translated by Oleg Prokofiev and edited by Christopher Palmer contains family photographs and some of Prokofievís short stories. Also consulted were the article in New Grove by Dorothea Redepenning, Prokofiev by Lawrence and Elisabeth Hanson, Prokofiev, A Soviet Tragedy, by Victor Seroff, several Soviet biographies, and a number of websites, most notably Prokofiev.org.

General information and photographs: http://www.Prokofiev.org

Complete list of works, compiled by Onno van Rijen: http://home.wanadoo.nl/ovar/prokwork.htm

1891

Born Sontsovka (now Krasnoje), Ukraine, April 23.

1896

Piano lessons with mother. First piano compositions.

1899

First trip to Moscow, sees Gounodís Faust and Borodinís Prince Igor at the opera, Tchaikovskyís Sleeping Beauty ballet. Later attends opera and ballet in St. Petersburg as well.

1902/3

At Taneyevís suggestion, private study with GliŤre in Sontsovka during the Summers.

1905

Begins study at St. Petersburg Conservatory. Blunt, irreverent manner offends many. Returns to Sontsovka in the Summers.

1906

Begins lifelong friendship with Miaskovsky.

1909

"Opus 1," Piano Sonata in f, actually his 50th composition.

1910

Performs Opus 1 in Moscow and begins conducting and playing in public.

Father dies; P. and mother sever connections to Sontsovka.

1913

Travels to France, England, Switzerland with mother. Scandal at premiere of 2nd piano concerto in Russia.

1914

Graduates from Conservatory; wins Rubinstein prize playing his own 1st piano concerto. Travels alone to England via Stockholm. Meets Diaghilev. Back in St. Petersburg by August 1. Beginning of war, is exempted from military service.

1915

Travels to Italy via Greece. Meets Stravinsky. Diaghilev rejects Alla and Lolly, contracts P. to write Chout.

1916

Successful premier of Scythian Suite in Russia.

1918

Flees Russian Civil War via Siberia, Tokyo, and San Francisco. Successful New York debut.

Meets future wife Lina in New York.

1920

Settles Mother in Paris. Successful Los Angeles debut.

1921

Scythian Suite and Chout premiered in Paris to great success. Love for Three Oranges and 3rd Piano Concerto premiered in Chicago to local critical success. New York critics retaliate viciously.

1922

Leaves USA to settle in Bavaria with mother. Richard Strauss is a neighbour. Enthusiastic London and Paris debuts of 3rd Piano concerto. More arguments with Stravinsky, friendship with Koussevitzky.

1923

Marries Lina.

1924

Settles in Paris with wife and ailing mother. Son Sviatoslav born February 24. Many concerts to earn money. Mother dies December 13.

1925

Unsuccessful Paris premiere of 2nd Symphony.

1926

Successful American tour organised by Koussevitzky. Italian tour.

1927

Triumphal return to Russia via Riga, Latvia. Richter, Gilels and Oistrakh in the audience at P.ís Odessa concert. Successful Paris premiere of Pas díAcier ballet. Bruno Walter rejects Fiery Angel for Berlin Staatsoper.

1928

Second son Oleg born in Paris, December 14.

1929

Successful premieres of The Gambler, 3rd symphony, and Prodigal Son ballet. Diaghilev dies August 19. Brief return to Russia.

1930

Very successful tour of USA and Canada sponsored by Koussevitzky. Meets Stokowski. Cool reception for premiere of 4th symphony in Boston, USA.

1931

Successful premiere in Washington, D.C. of 1st string quartet. Paul Wittgenstein bluntly rejects 4th piano concerto.

1932

Visit to Russia and publicly stated intention to return. Cool reception to Paris premiere of On the Dnieper ballet.

1933

Fourth visit to Russia. Score to film Lieutenant Kizhe.

1934

International success for Lt. Kizhe Suite. Regular journeys between Moscow and family at home in Paris.

1935

Romeo and Juliet ballet and 2nd violin concerto composed.

1936

Beginning of official crackdown on Shostakovich and other Soviet composers.

Closes Paris apartment and moves with family to Moscow. Peter and the Wolf very successful.

1937

American tour. Cantata for the 20th Anniversary of the October Revolution found unsuitable for performance by Russian authorities.

1938

Last American Tour, with Lina. W.W.II closes off European travel. Alexander Nevsky, 1st cello concerto premiered in Moscow. Romeo and Juliet premiered in Brno, Czechoslovakia.

1939

Summer in Kislovodsk in the Caucasus. Meets Mira. Arrest of Meyerhold.

1940

Successful Romeo and Juliet premiere in Leningrad. Shostakovich praises 6th piano sonata. Semyon Kotko unsuccessful.

1941

Richter plays Russian premiere of 5th Piano Concerto to great success. P. abandons family to live with Mira. Hitler attacks Russia. P. and Mira leave war-threatened Moscow for the Caucasus.

1942

2nd string quartet. Begins composition of War and Peace. Moves to Alma-Ata, Kazakhstan, to begin work on Ivan the Terrible with Eisenstein. Scores three war propaganda films.

1943

Return to Moscow. Richter premiers 7th piano sonata, which receives a 2nd place Stalin prize. P.ís music becomes very popular throughout the world. Back to Alma-Ata, then to Molotov (now Perm). Final return to Moscow.

1944

Oistrakh and Oborin premier violin version of flute sonata Op 94. Gilels premieres 8th piano sonata. Concert performance with pianos of War and Peace. Ivan the Terrible Part I premiered and wins Stalin Prize 1st class for both Eisenstein and P.

1945

Very successful premiere of 5th symphony and Cinderella ballet. Health collapses, enters hospital with severe hypertension; moved to sanatorium in Barkhiva. Well enough to attend well received premiere of War and Peace excerpts with orchestra, in June. On the cover of Time magazine USA.

1946

Jubilant 55th birthday celebrations in Russia. Ivan the Terrible Part II completed, officially denounced; Eisenstein forced to apologise. War and Peace Part I receives very successful first staged performance. Successful premieres for Betrothal in a Monastery and 1st violin sonata. Health worsens.

1947

Premiere of Part II of War and Peace cancelled by censors. Premiere of 6th symphony in Leningrad; at first successful, but later officially denounced.

1948

Marries Mira. Most severe ideological attack on Soviet composers. P. forced to confess and apologize. First wife Lina arrested and sentenced to prison. Eisenstein dies.

1949

Successful premiere by Rostropovich and Richter of cello sonata. Health declines further.

1951

Richter premieres 9th piano sonata. On Guard for Peace wins Stalin Prize second class.

1952

Awarded public pension. Composes Sinfonie-Concertante for Cello and Orchestra. Last public appearance at successful premiere of 7th symphony, October 11.

1953

Dies at home in Moscow, March 5.

© MusicWeb March 2003