In the beginning God created the heaven and the

earth. And the earth was without form and void; and darkness was upon

the face of the deep.

Thus the earliest steps in the creation of the world,

as reported in the book of Genesis, and it can be confidently asserted

that there has been no civil engineering project to rival it since.

Just assembling the materials must have been a challenge, and it’s perfectly

logical that once in place, and before he started trying to inject any

order into it all, God decided to create light so that he could see

what he was doing. And what he saw, unsurprisingly given the scale of

the job, was absolute chaos.

God had set himself a mighty task, and in 1796, Joseph

Haydn, a mere mortal, set himself the – for him – equally mighty task

of expressing it in music. His oratorio opens with a celebrated sound

painting of the chaos God saw once he spread his materials before him.

A lesser composer might have produced something full of loud discord

and rapid, aimless melody, but Haydn is far more subtle than that. In

his representation of chaos things move slowly, the different elements

of the earth abutting each other in no particular order; darkness is

there, certainly, and little is resolved. And yet the immense calm of

the mind of God as he contemplates the task he has set himself is also

uncannily present, as is a quite extraordinary sense of anticipation

of what is to come. And what follows is the separation of light from

darkness, represented by Haydn, as anyone who has ever heard The

Creation knows and will never forget, as an astonishing burst of

light on a C major chord from the choir and the orchestra. The rest

of the work follows the development of the project, recounted by three

angels, Gabriel, Uriel and Raphael. God took six days over the job –

with no penalty, as far as we know - for late completion. On the second

day he separated off some of his materials and made heaven, and on the

third day he organised things so that all the water flowed together

into a few places leaving dry areas which he called ‘land’ and where

he created plant life. He knew nothing about photosynthesis, which explains

why it was only on the fourth day that he created the sun, moon and

stars. (And we are bound to wonder where the light came from on that

first day.) On the fifth day he created all the creatures that live

in the sea and those which fly above the earth, and gave them the means

to renew their own species. On the sixth day he created all the creatures

that walk on the earth, including one that he called ‘man’. To these

creatures too he gave the means to multiply, and to man the specific

instruction to dominate and subdue all the rest, perhaps the only mistake

he made in the whole job. On the seventh day he rested, and so should

we.

Haydn began his Creation in 1796 and took significantly

longer than six days over it. He had been in London during 1794 and

1795, his second journey there and a huge personal triumph for him.

He was enormously impressed during his stay by the oratorios of Handel,

and returned home with the text, in English, of The Creation.

We don’t know who wrote this, but we do know that it was later translated

into German and to some extent adapted by Gottfried van Swieten. In

the text, as set by Haydn, the story of the creation is recounted mostly

in recitative with reflection and comment provided in the form of arias

and choruses. It’s quite a long work – around a hundred minutes in the

performance under review – and in three parts, of which the first two

deal with the creation proper – Part 2 ends at the close of the sixth

day of God’s labours – and Part 3 paints an idyllic picture of Adam

and Eve in the Garden of Eden. As a subject it was almost bound to appeal

to Haydn: there is nothing of the tragic here, and the only darkness

is at the outset where God and Haydn work together to create light.

And the story gives ample opportunity to the composer to exploit his

characteristic simplicity of utterance. By its very nature everything

about the earth and the creatures that lived upon it at this time was

innocent, unsullied by experience. We hesitate over the word ‘naïve’,

but it’s not a bad word to use, even if ‘simple’ and ‘childlike’ get

closer, perhaps, to the essential nature of the work. If the opening

of the oratorio, the representation of chaos, is musical sophistication

to the highest degree, the word ‘naïve’ certainly reflects well

the composer’s way in representing other things. The moment of the creation

of light is a wonderful coup de théâtre, and as

early as Raphael’s first recitative (Disc 1, track 4) we hear the composer’s

wonderfully childlike way with the thunder and lightning storms that

plague the earth on this second day, followed by the cooling rain, even

hail, and lastly, the light flaky snow. Similar techniques are applied

to parading before us the different creatures God creates, from the

bounding lion to the slithering worm, and the double bassoon has a short

and hilarious moment of glory in Raphael aria Nun scheint in vollem

Glanze (Disc 1, track 22) when we are told of the heavy beasts which

now tread the earth.

Killjoys over the years, Tovey amongst them, have pointed

out that the music of Part 3 is less inspired than the rest. Some have

even intimated that Haydn would have done better to rest, like God,

after the sixth day. Karajan and others have been led to cut passages

or even whole numbers from Part 3. Revisiting this wonderful work after

a long period of abstinence I’m disappointed that I now find this criticism

to be correct to some extent, though how much it matters is another

question. Parts 1 and 2 are made up of music of absolutely incandescent

genius, whereas Part 3 is slightly less so. Who are we to complain?

And besides, if we didn’t have this Eden scene we would have to do without

Adam and Eve, so innocent and sweet-natured – Eve had as yet to develop

an interest in fruit – like two youngsters, breathless, tentative, not

knowing if they want to be in love or are happy just being best friends

like before.

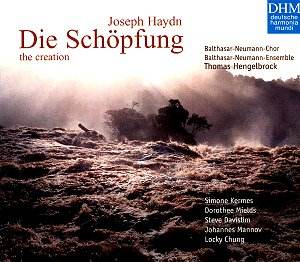

Almost anyone who has sung in amateur choirs for any

length of time will have sung The Creation at least once, and

given the wonderful music its popularity as a choral society standby

is only surprising in that there is not an enormous amount of choral

work in it. There is enough, however, and it is striking enough, to

provide contrast and points of drama where needed. There are twenty-eight

names on the chorus list accompanying this recording, though only eighteen

of them get onto the photograph. It’s a predominantly young person’s

choir, founded by the conductor in 1991, and they have all the sensitivity,

subtlety and virtuosity required for the work. The only thing they lack,

at certain moments, and that inevitably, is sheer weight. The orchestra

plays exceptionally well on period instruments, and if one draws attention

in particular to some lovely flute and clarinet playing this is not

to detract from the superb quality of the rest. A fortepiano is used

for the recitatives. The soloists are all outstandingly good, with particular

mention for Simone Kermes who sings the part of Gabriel. There is real

wonder in her voice as she tells us how all in heaven behold the marvellous

work that God has done (Disc 1, track 5). Her aria at the beginning

of Part 2 (Disc 1) beautifully expresses the different birds which begin

to colonise the earth, though I found her trills, as the dove coos to

his mate, slightly overdone. If Dorothee Mields and Locky Chung seem

marginally less vivid than the others this is probably more to do with

the limited range of expression demanded by the music than anything

else, and their evocation of Adam and Eve in the Garden is deeply moving

all the same. (A curiosity: Haydn does not ask for a solo alto in The

Creation, except for four bars in the final chorus. The singer is

not named here, which is a pity as she would be in excellent company

– on Karajan’s first DG recording these four bars are credited to Christa

Ludwig!)

Thomas Hengelbrock directs a clear and unfussy reading.

He has an excellent grasp of each of the different elements of the score,

which he communicates extremely well to his forces and thence to the

listener. His view of the work overall is integrated and forward moving.

He is an outstanding accompanist, most notably in Gabriel’s Part 2 aria

already mentioned, where he allows his soloist considerable freedom,

following her exceptionally well when she lingers yet at no time allowing

things to drag. He demonstrates, at times, a certain excitability however,

which is rather at odds with the essentially smiling nature of the music.

There are a few changes of tempo within individual pieces which seem

at least questionable, and the bliss expressed in the first part of

Adam and Eve’s duet (Disc 2, track 4) would have been more convincing

had the accompaniment been more affectionate, less staccato and accentuated.

One or two tempi seem over-rapid, too, especially in the choruses. The

great chorus which ends Part 1 (Disc 1, track 14) and which all amateur

singers know as The Heavens are Telling sets off at a tremendous

lick and at the point where the composer asks for an increase in tempo

the conductor doesn’t do much. At two subsequent points, however, he

does push the tempo on with the result that the reading of this chorus

has much brilliance but not very much joy. But the reading as a whole

is affectionate and convincing, and he totally avoids the kind of personal

accretions which disfigure Harnoncourt’s reading, a conductor with whom

Hengelbrock has frequently worked.

This is a thoroughly recommendable recording of Haydn’s

astonishing masterpiece overall, with much of its freshness of character

coming, I think, from the fact that so many young people are involved

in it. The conductor might have encouraged a slightly more carefree

manner from time to time, but that is the only criticism I can make,

and many may not even share it. Parts 1 and 2 are presented complete

on the first disc, Part 3 on the second. The booklet provides the sung

text and interesting contemporary translations into English, French

and Italian. The introductory essay is also interesting but the translation

is rather garbled.

There have been many excellent recordings of The

Creation and some of them approach, even if they do not attain,

the ideal. Sir John Eliot Gardiner’s reading is brilliant and technically

assured, but Haydn’s smile and childlike simplicity seem sadly absent,

and if period performance is important to you Hengelbrock’s performance

is to be preferred. Leonard Bernstein’s second reading, for DG, is constantly

smiling, and is notable also for the prominence he gives to the trombones

in the closing passage of The Heavens are Telling, a thrilling

moment. This performance has its overblown moments however, and though

I enjoy it very much not everybody will be so forgiving or indulgent.

For them, I recommend Münchinger on Decca, with Elly Ameling and

Tom Krause among the excellent soloists, and especially Igor Markevitch,

recorded in mono and published in 1958, with the incomparable Irmgard

Seefried deeply moving as both Gabriel and Eve.

William Hedley