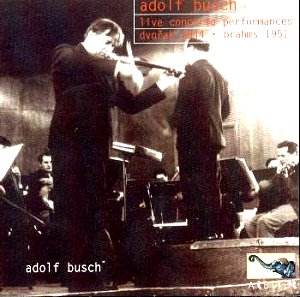

Arbiter’s catalogue boasts a number of performances

by Busch and by his Quartet. This one collates two works closely associated

with him in live performances. The Dvořák

dates from 1944 in New York and the Brahms comes from Basel in 1951,

his last performance – increasingly ill he died the following year.

His Brahms was never recorded commercially but we now have two off-air

survivals; this and a Music and Arts William Steinberg led performance

from 1943. There is also a live Finale from a different performance

that was previously the only known example of his Concerto performances.

Note writer Tully Potter writes with predictable understanding about

Busch but his assertion that he was the Brahms’ Concerto’s "leading

exponent in the years between the Wars" can be taken with a pinch

of salt (Huberman? Kreisler?). A leading exponent, maybe.

I am a great admirer of Busch but this Brahms finds

him, as Potter admits, in decline. The sound quality is generally good,

a little muffled and with some acetate damage (there seems to have been

some little damage at 0.30 in the orchestral introduction but it passes

quickly) but quite sufficient to allow uninterrupted scrutiny of Busch’s

performance which differs markedly from that Finale performance and

from the swagger of the Steinberg 1943 performance. Hans Münch

(cousin of Charles) is a sympathetic accompanist but even he can’t prevent

Busch rushing his passagework in the first movement and the sense of

him jumping his bars. His playing from 10.30 is decidedly sketchy and

his technical frailties probingly apparent. It’s good to hear his own

first movement cadenza. The slow movement enshrines the carapace of

a once fine conception; the oboe solo is good, Busch making a couple

of quick and colourful slides but there is some lack of orchestral clarity

behind him and once or twice there is pitch distortion on the recording.

Busch’s once ebullient way with the Finale now sounds decidedly and

inevitably perhaps far more tired and effortful. He was always animated

and quick here and he’s still less then half a minute slower than the

Steinberg performance but here the tone takes on a slightly smeary and

artificial-sounding emotiveness.

The companion Dvořák

with Leon Barzin dates from the latter stages of the War. He had performed

a lot of Dvořák (but recorded only the Op. 51 Quartet) so it’s

certainly of major importance to hear his Concerto performance and in

such good sound. It’s a strong and forceful traversal but one

that remains unconvincing. His first movement sports some didactic passagework

and a distinct lack of plasticity of phraseology. There is too much

emphatic playing and, as with the Brahms, Busch is guilty of rushing

bars. As a result the opening movement for much of the time sounds rhythmically

jerky and casually eruptive, despite some delightfully emotive moments

from the soloist. As the movement develops one can however feel him

becoming more idiomatic even if the recording fails to flatter the famous

and much mused upon Busch tone. Barzin shapes the opening of the second

movement with real understanding but Busch does make some rather unlovely

sounds – his lower two strings are the main culprits – and his tone

tends to thinness. For all the occasional delight of his playing the

tonal and concomitant technical liabilities are too pronounced here.

The National Orchestral Association sounds bluff rather than inspired

in the opening of the finale and Busch seems to be tiring rapidly (there

is more evidence of technical limitations). Nevertheless the way he

varies his phrasing, keeping the lyric line constantly energised, is

treasurable even if his entry points are really very emphatic indeed.

The result is a fitful, not entirely cohesive performance.

The irony of the German Busch performing Dvořák

in New York in 1944 whilst the Czech Prihoda had slightly earlier recorded

it in Berlin won’t go unnoticed. Whatever ones position regarding the

moral implications involved these should remain independent of ones

judgement of the performances. The Brahms

is a study in decline and the Dvořák a most unusual, not entirely

successful, traversal. I would however strongly urge those interested

in Busch seriously to study the disc; what it discloses, even by default,

is of significance.

Jonathan Woolf