There’s no long orchestral exposition here to give

the soloist time to warm the stool, just a couple of bars of "on

your marks" music then off she goes. Still, it’s all right, because

she’s given beginners’ music to play, just a simple melody in octaves.

Even the reviewer would be able to play the first couple of minutes

of this particular concerto, and what a wonderful time he would have!

All the same, I suspect that it’s actually easier for the soloist to

begin with more demonstrative music – massive chords à la Tchaikovsky

1 or hair-raising semi quavers (after a ravishing orchestral introduction)

as in Prokofiev 3 – than music as simple as this which, at the same

time, represents a major part of the thematic material of the whole

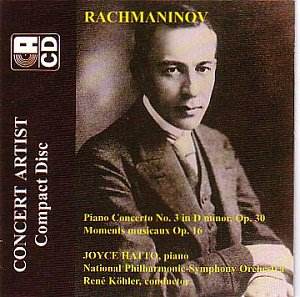

work. Well, Joyce Hatto will be relieved to know that she has nothing

to fear from me. She delivers this opening melody most sensitively,

her playing limpid and poised. At the same time she manages, as is the

way of a great artist, to inject this very simple music with all its

import and meaning, engaging the listener’s attention from the outset.

The arrival of the solo bassoon to play in duet with her after a few

bars demonstrates another feature of this performance: the outstanding

quality of the solo wind playing. Miss Hatto’s feeling for rubato

– around 4.00 in this first movement is a good example – demonstrates

a profound sympathy with the Rachmaninov style, and when this same music

returns in the recapitulation the calm she communicates is quite magical.

She plays the longer, more difficult of the two cadenzas Rachmaninov

provided. This was apparently the one the composer preferred, even if

he played the shorter one when he recorded the concerto himself with

Eugene Ormandy.

The slow movement is more elusive than the other two,

and may even seem inconsequential in comparison. Rachmaninov calls it

an intermezzo, which goes some way to explaining this. I think it is

particularly difficult to bring off, technical issues aside, and in

spite of some beautifully characterful playing from both the soloist

and the orchestra I do find the more withdrawn passages of the movement

a shade less communicative than what has gone before. No such suspicion

can be entertained about the more brilliant central section, however.

There is again some beautiful duet playing, starting around 7.00, first

with the flute then with the horn. The finale, which follows without

a break, is superbly played, very rhythmic and march-like when required

and movingly poetic in the more passionate, yet strangely fragile, second

theme. Joyce Hatto has all the technical means at her disposal, from

rapid pianissimo playing to enormous power when called for. She communicates

her view of the concerto direct to the listener, who is, I submit, totally

convinced. "With a safe pair of hands," the liner notes tell

us, speaking of the end of the work, it "rarely fails to bring

the audience to its feet." Miss Hatto’s are certainly a safe pair

of hands: in this performance the music rises to a superb climax and

the work ends in stupendous fashion with a final kick on the accelerator.

Joyce Hatto receives outstanding support from the National

Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra. It doesn’t matter who they are, their

playing is tight and hot, with all departments equally excellent. They

accompany their soloist in a most exemplary manner, together in more

ways than one during her more fantastic moments. This is of course a

credit to the late René Köhler who conducts the work with

the utmost care and control. Particularly interesting is the way he

brings out certain subsidiary parts, often in the basses, revealing

an unexpected diversity of orchestral invention. Between them these

forces produce a performance of the third concerto as recommendable

in its own way as the two others I know best, by Martha Argerich or

Byron Janis, and praise doesn’t come higher than that.

The Moments Musicaux, are perhaps the first

of Rachmaninov’s solo piano pieces to show signs of his mature style.

They are also very interesting and lovely in their own right. I’d never

heard them before and I’m looking forward to getting to know them better.

Perhaps the 3 against 2 writing in the first piece sounds just a bit

literal in Joyce Hatto’s performance, but everywhere else I found her

playing most convincing, most of all in the dark melancholy – present

here, and so typical of the composer, even in this young man’s music

– of the third piece in B minor.

William Hedley

MusicWeb

can offer the complete Concert

Artist catalogue