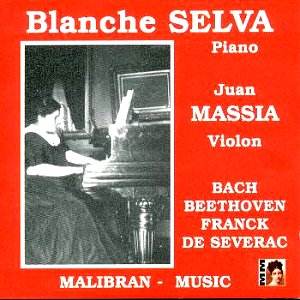

Blanche Selva, one of the most revered of French pianists

of her generation, made pitifully few recordings and even those were

compressed into a two-year period. Her discography in fact amounts to

no more than a mere eleven works, three of them in collaboration with

the Catalan violinist Joan Massia (two of which Malibran present here).

Six of the eleven were of works by Déodat de Séverac –

who still retains a tentative toe in current discographic waters – two

were by Bach, two by Franck and one by Beethoven. This is a small return

for so important a figure but, accustomed to resurrecting leading figures

of French inter-war life, Malibran has come to her rescue (and incidentally

to Massia’s as well – there wasn’t room here for their Columbia set

of the Franck Violin Sonata so maybe Malibran will include that in a

forthcoming issue).

Trained at the Schola Cantorum, Selva was appointed

by d’Indy himself as teacher at the early age of eighteen. In all she

taught there for twenty years and was adventurous enough to add her

own twist to the usual continental drift westwards of Czech musicians

– Selva herself moving to Prague to teach (at around the time Martinů

and so many others were off to Paris) and encountering Suk and Novák

along the way. She was a front rank exponent of Albeniz, d’Indy himself

(Malibran’s notes say that Selva “detached herself” from the Schola

Cantorum in the early 1920s but I was under the impression that

she and d’Indy fell out), Roussel and many others. She gave the complete

Bach keyboard works as a cycle (beginning in Paris in 1904 and a number

of times after) as she subsequently gave the complete "32"

of Beethoven on several occasions. She settled in Catalonia in the mid-twenties

but suffered a stroke shortly after making some of the discs to be heard

here and from then her concert-giving days were over. She left Barcelona

– where she had taught – after the Civil War and died pretty much forgotten

in France in 1942.

Her Bach Partita is a precious souvenir of her playing.

The Prelude is limpidity itself and the clarity and pointing of the

stylish and apt Allemande truly impressive. Her chordal weighting in

the Courante and her rather cool undemonstrative musicality all point

to a major Bach player of the most august French school. The dynamics

of the concluding Fugue are splendidly controlled and her throwaway

ending insouciant in the extreme. If anything the Franck is even better

and stands alongside the almost contemporaneous Cortot recording as

twin poles of French School Franck interpretation. She plays the Prelude

with exceptional understanding of line and depth of weight, a tremendous

sense of clarity and a control that never precludes metrical freedom.

The rolled chords of the Choral disclose a movement that is short neither

on detail nor on affection; nothing however is unduly romanticised and

everything is subordinated to acid architectural considerations. Hers

is a deeply serious and affecting musicality – the finger slip at 4.35

unquestionably let through in the interests of heightened expressivity.

The purposeful warmth of the Fugue is not compromised by unnecessary

lingering; reminiscences of the second movement are all the more moving

for their sheer unvarnished candour. Wonderful playing.

She was long a proponent of the music of the Languedoc-Provencal

composer Déodat de Séverac and even wrote a biography

of him. She revels in his fresh air impressionism – how elliptically

she points the end of Baigneuses au soleil and how charmingly

she vests Vers le mas en fête with such drama and such

colour. To the mild exoticisms of Les muletiers devant le Christ

de Llivia can be added Selva’s own virtuosity and flair for colouristic

potential – and she somehow ties the work to its Franckian antecedents

with the simplest of inflexions. She joins with Massia for the Bach

movement from the third Violin Sonata. He has a rather thin tone, unwarmed

by much vibrato, and his shifts sound surprisingly awkward. His trill

is also inclined to be a bit rough and his whole musicality is profoundly

old fashioned in the context of the day. Selva is quite a way back in

the balance unfortunately. In the Spring Sonata one’s initial

impressions of Massia are reinforced. He is inclined to be heavy going

in the opening Allegro, slow and with unvaried and limited vibrato,

prominent portamenti. Selva is once again somewhat occluded in the balance

but we can still hear and admire her animated rhythm and her subtle

bass pointing. The slow movement is reasonable but some of the jokey

rhythms of the Scherzo are rather smoothed over and the finale is short

on humour and elation – its soft grained nature co-exists with fine

co-ordination between the two and Massia does essay some lightly textured

bowing that is interesting to hear. On this showing however Massia was

No. rival to the much more forward-looking tonalist and compatriot Manuel

Quiroga – whose glinting, glittering morceaux discs rather put the antiquated

Massia in the shade.

This is a prized disc. Selva’s small body of recordings

is conspicuously important and we have a sizeable chunk here. For all

my strictures Massia is an engaging and by no means unimportant figure

in Catalan music making; his Franck Sonata with Selva conforms to the

qualities and limitations expressed earlier but Malibran would do a

great service in publishing it. I’d also never seen a picture of the

obscure fiddler and courtesy of the booklet I’ve now seen two. To those

whose prerequisites in French pianism of the 1920s are Cortot, Cortot

and more Cortot (maybe with Lortat thrown in as a sop) I recommend this

without reservation.

Jonathan Woolf