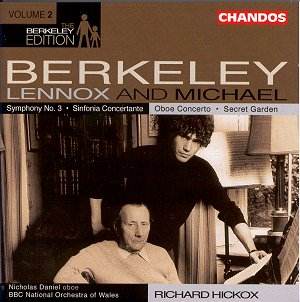

Despite the gap of a generation, only four years separate

Lennox Berkeley’s Sinfonia Concertante from his eldest son’s

Concerto for Oboe and String Orchestra. The Sinfonia Concertante

also features a prominent part for solo oboe and both works were written

for Janet Craxton, a performer whose mantle has perhaps been handed

over to the fine soloist here, Nicholas Daniel. This however is where

the comparisons end for in the case of Berkeley senior his later works

were notable for their economy of expression and melodic astringency.

Michael on the other hand, at the time of his Oboe Concerto in

1977, was still trying to find his own voice, a challenge that must

have been daunting given the myriad of influences that he heard around

him through his father’s wide circle of composer friends. As a result

the early tonal, unashamedly melodic, even lush style demonstrated in

his Concerto, was later to be dispensed with in favour of a considerably

more adventurous approach, rather going against the grain for a younger

composer whose contemporaries were, in a number of cases, moving in

the opposite harmonic direction and abandoning atonality in a move towards

the "post-modernist" ethic.

Lennox Berkeley’s later economy is best demonstrated

here by the Symphony No. 3, a tautly constructed, even terse work in

one fourteen minute movement, albeit falling into three readily identifiable

sections and conveniently tracked as such on this disc. Berkeley makes

use of a somewhat diluted approach to twelve tone technique, much of

the material stemming from the opening motif which contains part of

the chromatic germ from which the rest of the symphony is to grow, giving

the work its characteristic sound-world. The result is impressively

argued and aurally coherent if veering slightly towards the cerebral,

a point that is emphasised and made all the more obvious by the stylistic

changes that his music had undergone by this point.

Interestingly the premiere of the Sinfonia Concertante

was given at the same Prom as the London premiere of the Third Symphony,

a concert that commemorated Berkeley’s seventieth birthday. What a great

pity it is that a number of other important British composers who have

celebrated similar milestones since were not afforded such an honour!

Although written four years later than the Symphony the Sinfonia

Concertante turns out to be the more expansively melodic of the

two works, no doubt due to the composer’s specific intentions in writing

for Janet Craxton and his desire to demonstrate the "oboe’s aptitude

for melodic expression and expansion" rather than as a "vehicle

for the display of virtuosity"; not that the work is lacking in

technical fireworks as the second movement Allegro vivace shows.

However, contrast this with the sunny fourth movement Canzonetta

and one can clearly see what the composer was wishing to achieve.

The work is beautifully and idiomatically written for the solo instrument

and Berkeley’s scoring for his scaled-down orchestra, coupled with a

touch of added colour from the piano is exquisitely done. Of the two

works it is the impressive concision and cohesion of the Symphony that

creates the more striking impression.

I clearly recall hearing Michael Berkeley’s early Symphony

in One Movement: Uprising, for the first time and being astonished

by its, at times, almost literal debt to Stravinsky, in particular the

Symphony in Three Movements. In point of fact the Symphony

appeared in 1980, three years after the Oboe Concerto, although

in the concerto it is the composers who surrounded Berkeley during his

youth, close friends of his father, that seem to exert the strongest

influence on the young composer. The year Berkeley began work on the

concerto saw the death of his godfather, Benjamin Britten, and as a

result the work became a memorial to his father’s great friend. Indeed,

the final movement carries the title, Elegy: In memoriam Benjamin

Britten, although echoes of Britten also seem to hover in the opening

movement. The central Scherzo: Allegro vivace is closer to his

father’s music and perhaps not a long way from the language of Kenneth

Leighton. Stylistic concerns aside however it is the young Berkeley’s

ability to carry a sustained melodic line that makes the concerto worthwhile.

Nicholas Daniel takes full advantage in a performance packed with atmosphere

and gloriously singing solo playing.

Secret Garden serves as a good example of what

Michael Berkeley’s music has become. It is not devoid of melody but

is set against a more adventurous backdrop of harmonic freedom creating

a harsher soundworld in which dissonance plays an integral, if controlled,

part. The piece takes the listener on a journey through the recesses

of the mind, following paths that are sometimes quickly aborted or can

lead to further discoveries. The orchestration is exciting, the overall

invention possibly less so, but the blazing closing paragraphs are undeniably

impressive and had me reaching for the remote for a repeat hearing.

Chandos’s recording is finely captured in the spacious

acoustics of Swansea’s excellent Brangwyn Hall. The strings in the Concerto

have both warmth, natural depth of tone and admirable rhythmic clarity

whilst the dynamics of the orchestra in full flight are truly thrilling

(try the aforementioned closing bars of Secret Garden). Ultimately

though it is Nicholas Daniel that steals the show. His playing demonstrates

a musicianship that ranks him amongst our very finest instrumentalists

and his contribution to this release cannot be underestimated.

Christopher Thomas