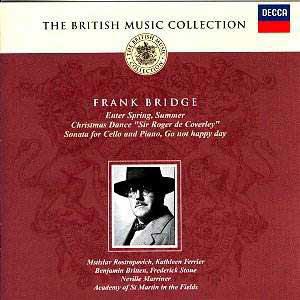

Frank Bridge could so easily (and unfairly) be

seen as the follower of various camps. His early British pastoral impressionist

manner hardened in the furnace of the Great War into something far closer

to the Second Viennese School: more Berg than Webern. On one side of

the divide stand works such as the carefree Summer and romantic-impressionist

suite The Sea. On the other side stand works of uncompromising

spareness. The later works include Phantasm (piano and orchestra),

Oration (cello and orchestra) and the String Quartets 3 and 4.

Enter Spring rather confounds the simplistic

idea of a divide. It is a crucible in which the carefree lush pastoralism

of Summer meets impressionism and the Schoenberg of Pelleas

and Melisande. It is a work that sometimes is evocative of the dewy

forests of Bax's Spring-Fire and at others takes on a unique

quality all Bridge's own. The first stirring of the march of Spring

emerges in birdsong and hesitancy but with growing swinging confidence

(9.30). The tolling swaying march bursts with all the confidence and

newness of Nielsen’s life-force. At 11.06 the sub-motif calls out 'blessed

art thou' then the great swinging bell-figure rolls forward with blessed

remorselessness at 11.55. There are even echoes of La Valse at

13.00. The jagged energising hammer-swung power of this music is staggering.

The force which Bridge taps into or expresses is the same force that

blasts forward Nielsen's Fourth, John Foulds' April-England and

even the latter part of Finzi's Hardy song Regret Not Me. This

is the same 'apple-tree shaker' that promises violent rebirth. At one

level the work matches another much later piece - also march-driven

- William Alwyn's Symphony No. 5 Hydriotaphia though the force

of the Alwyn has more to do with tragic mortality than with rebirth.

Marriner makes a very good job of Enter Spring;

better than his Bax November Woods originally issued on the

same CD with Foulds' April-England. Groves in his classic 1974

EMI recording is even better at imparting symphonic weightiness. I always

'feel' Enter Spring as a compact symphony rather like the Alwyn

5, Rubbra 11, Lambert's Music for Orchestra and, further afield,

like Sibelius 7, Pohjola's Daughter and Harris 7.

Summer is done in lush manner. The work is a

gem of almost tactile scene painting. Gentle zephyrs play rather than

rough winds shaking ‘the darling buds of May’. The ASMIF are augmented

to large symphony orchestra proportions and it shows. Marriner gives

Summer its most expansive and confident outing. The work has

links with Butterworth's Shropshire Lad and Two Idylls. Those

summers were soon to be trodden down by muddy boots, field grey, khaki

and tank tracks.

The clever and far from long-winded Roger de Coverley

was also recorded by Bridge pupil, Benjamin Britten. This is played

with elan and explosive pizzicati as well as with a Scottish snap joyously

capped by Auld Lang Syne (a tune on which Joseph Holbrooke in

1917 wrote a set of symphonic variations) kept as a surprise at the

end.

Classic Bridge interpretation for the Bridge Cello

Sonata. What more could you ask? Britten and Rostropovich dig deep into

the continental passion of this compact Sonata. This is the revolutionary

antithesis of the British stiff upper lip caricature. Rostropovich excavates

fathoms of tone and sustains that tone without tremor - rock solid.

This work is from 1917 and if at times it plays as if a Canute-like

spell against the times it is certainly a touching and passionate piece.

In the second movement the confidence has been corroded and the harmony

has soured.

Kathleen Ferrier is as steady of tone as Rostropovich

in Go Not Happy Day though the recording shows its ago in this

fresh company. She does this little song to perfection. I was especially

impressed by her careful attention to dynamics. The song satisfyingly

rounds out this excellent if comparatively short-playing collection.

The brief notes are adequate. No texts for the song,

I am afraid.

Rob Barnett