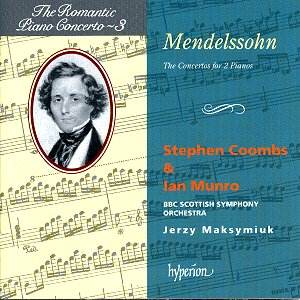

A glance at the dates shows that these were teenage

works. A glance at the disc’s overall timing also shows that they are

both very substantial pieces, which is not surprising, given that the

teenage Mendelssohn was possibly the greatest child prodigy in music

history. As Julian Haylock’s typically informative note tells us, Mendelssohn’s

piano style was "derived not so much from the orchestral texturing

of Beethoven and Schubert, as from the filigree intricacies of the German

virtuoso piano school, represented principally by Weber and Hummel".

He was not so much out to push forward the boundaries of the contemporary

instrument as to exploit its best qualities – brilliant treble clarity

and the ability to sustain a flowing, cantabile line. The two

concertos on this disc exemplify these qualities admirably.

Both concertos had been dropped from the repertoire

and were entirely forgotten until, in 1950, the original manuscripts

were ‘rediscovered’ in the archive of the Berlin State Library. It seems

certain that the E major was written for the composer to play

with his sister, Fanny, who was also a gifted pianist. The A flat

could have been inspired by his first encounter with another astonishing

young piano virtuoso, Moscheles, though whether they ever played the

piece is not known. The main criticism of these Double Concertos has

been Mendelssohn’s tendency to overstretch flimsy melodic material,

an unusual amount of repetition having to take place in order for the

two soloists to have an equal share. This is true to an extent, and

virtually predictable in one so young, though his astonishing mastery

of form and structure was not too many years away. Once one accepts

the blissfully naïve, untroubled nature of the music, there is

a great deal to enjoy. Indeed, given such refreshingly direct, unmannered

and scintillating performances as here, the works emerge with astonishing

creativity and flair, clearly showing a composer on the verge of artistic

maturity. Sample the delectable 6/8 Adagio of the E major,

which anticipates Mendelssohn’s Lieder ohne Worte style, the

melody spun with seemingly unending elegance and grace. The semiquaver

pyrotechnics of the finale show the Hummel influence, but this is never

mere note-spinning – one is always aware of continuity of line and direction

of development. The first movement of the A flat, one of the

composer’s longest concerto movements (17.16), displays true internal

balance and an emerging awareness of structural proportion. The delicate,

wistful Andante foreshadows the later G minor Piano Concerto’s

slow movement, and Coombs and Munro clearly enjoy themselves enormously

in the Allegro vivace finale, where the mixture of boyish naivety

and Weber-ish high spirits is truly infectious.

Recording quality is good, with balance between the

two pianos and orchestra well realised. Support from Maksymiuk and the

BBC Scottish is excellent, with sympathetic strings and delightful wind

playing. It is good to occasionally indulge oneself in music that has

no intention of plumbing the depths, and the charm and sheer ‘likeability’

of these two pieces make them very hard to resist.

Tony Haywood