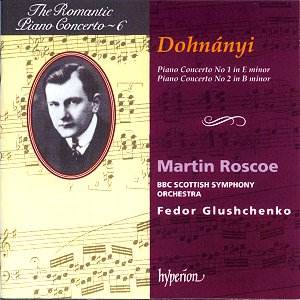

The Hungarian composer Ernst (Ernö) von Dohnányi

is well known in his homeland but less celebrated internationally. Over

the years his most famous composition has been another piano concerto,

the Variations on a Nursery Song, but in truth he was prolific,

and was admired by fellow musicians from the time of Brahms (whom he

knew) through to his final years in the United States.

As a young man Dohnányi was a virtuoso pianist,

and it shows in his Piano Concerto No. 1, which he composed in

1897-98. It is nothing if not substantial in scale, lasting for a full

45 minutes, and cast in the conventional three-movement design with

the slow movement at the centre. The style is very much of its time,

with a full awareness of Liszt and Brahms, but without the challenging

qualities of the harmonic language of Bartók.

There is an heroic, almost epic quality about the outer

movements, both of which approach 20 minutes in duration. This puts

a strong demand upon the soloist, of course, and in this sense Martin

Roscoe does not disappoint. For he is a splendid pianist, who sounds

very much inside the music and thoroughly in command of the technique

required. If there is a criticism of the performance it is probably

more to do with the balancing of piano and orchestra, since the solo

piano does sometimes sound swamped by the massive orchestral sound,

and details of articulation can disappear. Of course Dohnányi's

skilful orchestration does not always place this consideration uppermost

on the agenda, and in a movement of the size and scale of the opening

Allegro maestoso there are many turns of direction and manner.

In the First Concerto the slow movement is perhaps

the best. A brave and imaginative touch in the orchestration is that

the strings play pizzicato for most of the time, while the melodic shaping

is derived in large part from a subtle transformation of first movement

material. It is all particularly well judged, and Roscoe plays with

care and taste in every bar.

The finale returns to the heroic epic scale, and becomes

more compelling as it reaches its final stages. Here Roscoe and the

orchestra sweep the music on to a particularly exciting conclusion,

just what the romantic piano concerto is all about.

There are fifty years between these two concertos,

though the listener would not know it from the music. The Piano Concerto

No. 2 was completed in 1947. It remains romantic in style (thus

justifying its position in Hyperion's series), but the construction

seems tighter than that of its earlier companion, and it is none the

worse for that. This is reflected in the length, which comes out at

around the 30 minute mark.

Again there are three movements in the traditional

sequence, but the large first movement dominates the work, forming a

half of its duration. Dohnányi opens with a theme which he develops

obsessively, in the style of a motto, but there is also room for more

indulgent lyric romantic gestures. The artists manage these contrasts

well, maintaining the flow and convincing the listener of the structural

purpose.

In his useful insert notes, the distinguished musicologist

Otto Karolyi refers to the slow movement as occupying 'a stylised Hungarian

gypsy style'. But it is not an indulgence, for in the final two movements

the unity of the conception is a real priority, as the motto returns

and the lively finale emerges as the only possible conclusion for the

whole work. Again Roscoe is a convincing interpreter. Of the two concertos,

the more carefully constructed Second is probably the more compelling,

but the experience both works offer is thoroughly satisfying, and wholly

justifies Hyperion's foray into this little known territory.

Terry Barfoot

Complete

Hyperion Romantic Piano Concert series