The Eroica wasn’t as problematical a recording as

the Pastoral. Beecham and the RPO went into the recording studios

on 20th and 21st December 1951 returning in August

1952 to cover some edits of the first and third movements. He conducted

the Eroica at least forty times during his career and it was, in fact,

the last Beethoven Symphony he was to conduct, in Chicago in 1960. It

goes without saying that the RPO is on splendid form with particularly

notable contributions from Jackson, McDonagh, Brymer and Brooke and

there is a pervasive sense of alluring tonal beauty throughout, though

not a preening one.

There is a real sense of articulated clarity in the

opening movement, especially in the strings. Tuttis are never saturated,

the orchestral weight never becomes heavy, with the basses subsumed

into the string patina – this is certainly not a Germanic "bass-up"

performance; sonorities are equable, accents are often adroitly cushioned,

second violin entries always audible and full of character. It’s certainly

not the quickest of first movements and doesn’t quite possess the blistering

concentration of symphonic weight that some of his contemporaries would

generate from the score. It is nevertheless full of incident and imagination.

The Marcia funebre is proportionately sized; it possesses weight

and seriousness but not Brucknerian depth. Beecham’s performance perhaps

amplifies something that Neville Cardus wrote when he noted that Beecham

had "rid the music of nineteenth century weightiness and tonal

gestures supposedly earth-and –heaven shattering."

His rhythmic acuity and impetus is the means by which,

instead, he conveys thematic causal connections, how he generates motion

through almost imperceptible rubati. There is a generous fluidity to

his music making here but not one that aspires to the unshakeably monumental.

This applies especially to the Scherzo – though this is rather more

Allegro than the modified Allegro vivace as marked. The finale is ruminative,

measured and whilst rhythmically supple occasionally fitful. Oboist

Terence McDonagh shines here especially but all the principals are superb.

No overwrought sonorities impose themselves in Beecham’s conception,

which is serious and understated and never superficial. Coriolan is

full of elegance and dynamic gradients, vigorous orchestral exegesis

and drama, and admirable. Notes are once more by Graham Melville-Mason.

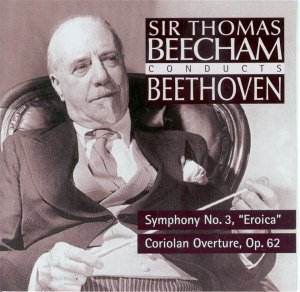

I like the photographs of a Beecham variously avuncular, amused, thoughtful

and pensive; it complements his Beethoven enshrined within.

Jonathan Woolf