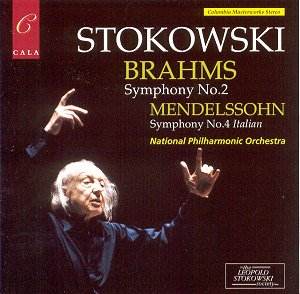

Recorded in 1977 shortly before Stokowski’s death these

performances have a linear cogency and articulacy of expression that

are little short of remarkable and would be so in any conductor, of

any age, at any time, much less one of ninety five. It’s tempting to

conjure up the alchemical or the visionary to try to explain Stokowski’s

unerring rightness but that is to ignore the obvious evidence of sheer

hard work, adroit musical understanding, advanced ear for orchestral

sonorities and a lifetime’s experience.

In fact, oddly, Mendelssohn was not a composer who

much features in Stokowski’s recorded legacy nor, it has to be said,

in his concert programmes. His first conducted the Italian in

1914 in Philadelphia, again in 1917, and this seems to have been the

last performance until this 1977 studio recording, a really rather remarkable

lacuna. His effortless launching of the Allegro Vivace at a tempo

guisto (if you know Cantelli’s live broadcast performance you’ll think

it’s a different work) is supremely effective. The string and woodwind

choirs are adroitly balanced and for all that this is big band Mendelssohn

it is flexible, responsive and superbly mobile music making. The final

passages of the first movement are marked by clarity and precision and

the control of dynamics in the development section earlier is entirely

admirable. Precise articulation and a strongly lyrical impulse inform

the slow movement; the balancing is well nigh perfect. The Minuet and

trio - the Moderato – features nicely judged layered string writing,

and not too much heft in the basses. The Saltarello is invigoratingly

alive, a minor key dance of life to which Stokowski responds with tremendous

brio.

The Brahms Second Symphony is obviously more a staple

of his repertoire. His was, after all, the first American-recorded set

of the complete Brahms Symphonies. First performed by Stokowski in Cincinnati

in 1912 he’d recorded it in Philadelphia in 1929. As his later Brahms

often reveals, clarity and architectural cogency allied to a strong

sense of momentum had become hallmarks of Stokowski’s approach. There

is a palpable sense of linearity supported by entirely appropriate instrumental

weight throughout. The clarinet counterpoint to the string theme in

the first movement or the beautifully accomplished entwining melody

at 6.30 or the well judged trumpet balancing at 8.40 – never forced,

never over bright, never submerged textually – are small, telling and

revealing incidents of magisterial control. Listen to the exemplary

pizzicatos in the second movement or to its melodic unravelling, the

non troppo marking properly observed or indeed to the sensitivity

of the National Philharmonic Orchestra, an ad hoc London group of stellar

accomplishment. This is a truly remarkable document of an ever-questing

musician - first movement exposition repeats taken in both works by

the way – whose final recordings are as noble, as understanding and

as true as one could ever wish to hear.

Jonathan Woolf