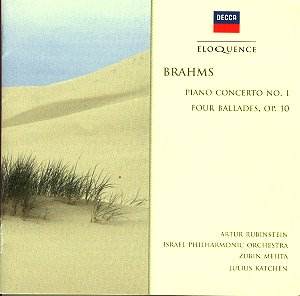

It is quite a feat to undertake a recording of Brahms

One in one's seventies. At eighty the task is Herculean. Rubinstein

was eighty-nine. It was his final concerto recording, in May 1976, and

followed his discs of the same work with Leinsdorf in Boston in 1964

and his earlier and most famous recording of the concerto with Reiner

in Chicago in 1954. Cyrus Meher-Homji’s part of the notes – which deal

with the performance whilst Carl Rosman’s deal with the work - are quite

honest about the technical limitations inevitably to be found in Rubinstein’s

playing. He quotes Mehta on the subject of the first movement’s development

section and its octave passages – these had constantly to be retaken

because Rubinstein’s failing sight meant he couldn’t see the right hand

notes.

This is a predominantly slow reading, still moving,

but not really comparable with the earlier recordings - and especially

that with Reiner – in either vigour or finesse. After a dramatic but

broad opening tutti Rubinstein enters at a much slower tempo, with very

slightly choppy rhythm. Not all his trills are clean and he has obvious

problems – as noted above – in those dramatic octave passages. Yet there

is something quietly and nourishingly compelling about the playing in

the slow movement - for all that the balance characteristically favoured

the soloist to an unnatural degree. The finale is slow but full of clarity

and playfulness. As throughout there are numerous finger slips – some

minor, some not – and listen at 7’01 for a particular example. But be

sure as well to listen at 10’00 to the insouciance and sheer cheekiness

of his playing, with his spicy treble fillips. Even at 89 he was incorrigible,

especially in the light of the immediately succeeding passage – very,

very scrappy.

Julius Katchen’s 1965 Ballades complete the disc –

a rather curious collection of virtues and demerits. There is much introspection

and glitteringly good playing but the Fourth is very fast and the opening

of Eduard never coalesces with the following tempo. Elsewhere

clarity and propulsion are paramount to the semi-exclusion of real and

consistent involvement.

An uneven disc then; it’s probably better to remember

Rubinstein’s Brahms One from his 1954 sessions than to persist with

the imperfections of old age in this moving but flawed last testament.

Jonathan Woolf

AVAILABILTY

www.buywell.com