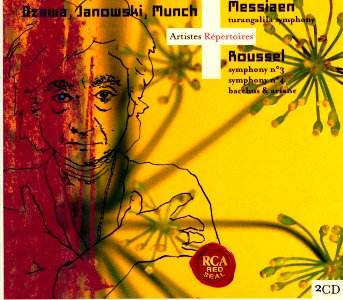

This issue brings together four brilliant recordings by three different

orchestras and conductors. They also cover a wide time-span; the Munch

Bacchus et Ariane from 1952, the Ozawa Turangalila from

1967 and Janowski’s Roussel symphonies from 1994. All three represent,

in their own ways, the best standards of their eras, and it’s a heady

experience listening to them. Bear in mind that RCA has always had a

characteristic way with recorded sound, basically aiming to knock you

out of your seat with sheer ‘pizzazz’. This is not to everyone’s taste;

while you feel right inside the orchestra, there is a flat, ‘front-lit’

quality to the sound that is sometimes tiring.

However, there is no denying the brilliance of the sound, the orchestra

and the conductor in Messiaen’s huge Turangalila Symphiony, which

accounts for the whole 77 minutes of the first CD of the pair. When

the LP of the Messiaen first appeared, it created a terrific stir, and

was in its way an epoch-making recording, especially as this work was

not then the ‘pop’ it has since become. For a long time the recording

has been ‘nla’, but it’s great to see and hear it back again, though

the modern competition in this particular piece is unusually intense.

Chailly’s account is of the same tendency as Ozawa’s, i.e. no-holds-barred,

while Previn’s performance, though it’s been around a bit, is still

up there with the very best. The piece itself is so famously OTT that

there is no sense in a conductor doing anything other than go for it

totally, and that’s what Ozawa and the superb Toronto Symphony do, egged

on by the RCA engineers. I have to say I’m not ultimately a fan of the

piece – don’t care for Messiaen’s music greatly anyway – but if anyone

can sell it to me, Ozawa can. After thirty-four years, that’s some achievement.

Mind you, CD transfers do have their dangers, e.g. the very noisy traffic

in the distance behind the ending of Jardin du Sommeil d’Amour’!

On CD2, we have a very different composer. Albert Roussel was a contemporary

of Nielsen and Sibelius, among others, and like them was committed to

symphonic composition. We have here two of his best known works, the

3rd Symphony and the second suite of music from his ballet

Bacchus et Ariane, as well as the lesser known 4th

Symphony. The striking thing about both the 3rd Symphony

and the 4th, which follows it on the disc, is their brevity.

The 3rd comes in at less than 25 minutes, while the 4th

is barely 20, yet they both feel like large-scale works. Janowski and

the French Radio Philharmonic give outstanding performances, energetic,

stylish and intense, revelling in the bright colours and strong thematic

material. The 3rd Symphony would make an ideal introduction

to Roussel for anyone unfamiliar with his music. The first movement

is full of driving rhythms, while the second is the emotional heart

of the work, rising to a massive, impassioned climax. The contrast with

this and the third movement, which could easily come from the sound-track

for a ‘Carry On’ film (and that is not intended as an insult!),

is particularly marked. The finale satisfyingly completes this great

20th century masterpiece. The 4th Symphony is

perhaps not quite so immediately striking, though it possesses the same

qualities and is just as enjoyable.

CD2 is completed by Charles Munch’s fine account of Roussel’s Bacchus

et Ariane music. The recording is quite exceptional for its age,

and few adjustments (aurally or mechanically) are necessary after hearing

the two more recent recordings. The Boston SO is of course a world-renowned

body, in large part because of Munch’s work with them, and they give

this gorgeous music everything they’ve got. The only strange thing is

that the important string solo passages sound less than convincing;

nothing horrendous, just not terribly good, and certainly not poor enough

to take the edge of desirability off this outstanding compilation.

Gwyn Parry-Jones