If, like me, your knowledge of the music of Vierne

is limited to his organ works and, perhaps, his fine Messe Solennelle,

this CD may be something of a revelation. His six organ symphonies,

composed between 1898 and 1934, are fairly well represented in the UK

catalogue, as are some of his other organ works. There are also at least

two recordings of the aforementioned Mass, which dates from 1899. However,

so far as I know these two chamber works have not previously been available

in the UK (though these are not claimed as premiere recordings, I see.)

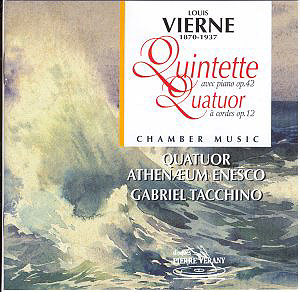

The String Quartet, which is placed second on the disc,

dates from about 1894 and is dedicated to Widor, with whom Vierne had

been studying since Franck’s death in 1890. By the time the work was

completed Vierne had been installed both as Widor’s assistant at the

Paris Conservatoire and as his deputy at the organ of the church of

St. Sulpice in Paris. In the informative liner notes we learn that Vierne’s

pupil, Bernard Gavoty regarded the piece as "an application of

the teachings of Widor." Apparently, Vierne came to feel that this

early work was not especially important in his oeuvre. Nonetheless,

the opportunity to hear it is most welcome.

It is cast in four movements. The first is a fairly

genial affair with arching melodic lines which are frequently supported

by syncopated rhythmic figurations. The scherzo-like Intermezzo is very

brief, lasting less than three minutes. The emotional core of the work

is the slow third movement which bears the tempo marking, ‘Andante,

quasi adagio.’ In fact, the pace alternates between these two speeds.

The opening material is a genuine adagio after which the second subject

is more agitated and the tempo picks up to andante before returning

to the reflective mood with which the movement began. The movement ends

in tranquillity. The busy finale begins as a moto perpetuo, the progress

of which is twice interrupted by a more lyrical subject. Towards the

end Vierne introduces a fugue, rather unconvincingly, before a brief

final reprise of the moto perpetuo. The Quartet is played with spirit

and finesse by the Athenaeum Enesco Quartet, who are Roumanian but have

been based in Paris since 1979.

They are joined by pianist, Gabriel Tacchino for the

Piano Quintet. This is a work of much greater substance than its earlier

companion. Partly, no doubt, this is because in the intervening period

between the two compositions, Vierne had developed his compositional

skills significantly. However, the circumstances which led to its composition

undoubtedly account for its power. Written between 1917 and 1918, it

was prompted by the death in action of Vierne’s son, Jacques, who was

aged just 17. Vierne confided to a friend that he was "…building

a votive offering, a Quintet of vast proportions, to convey the inspiration

born of my tenderness and my child’s tragic death."

The work has three substantial movements, the first

of which opens with a short introduction, which is dark and brooding

and which is largely for the piano alone. The first subject of the movement

proper is restless and dramatic. By contrast, the second subject is

a noble, easeful melody which appears first on the cello. The whole

movement is arresting and powerful and receives a performance which

is worthy of it, culminating in a rapt account of the sublime coda (8’

58" onwards).

The mood with which the first movement ended is carried

over into its successor which begins with a ruminative viola solo. Although

this movement s predominantly reflective in tone there are several passionate

outbursts and even when the music seems to relax "tension lies

lurking beneath its apparent calm", as the author of the notes

observes. After a sustained and powerful climax this movement also ends

in tranquillity.

The finale opens with striking piano chords which sound

like a call to arms. This is the start of a pregnant introduction after

which the turbulent music of the main allegro is driven relentlessly

forward like some dreadful cavalry charge until an awestruck piano solo

(5’18") ushers in a few moments of tense, ghostly calm. Then "the

charge" resumes and the music hurtles to a dramatic end.

This Vierne Quintet is a significant discovery. It

is imposingly played and the recorded sound is good. The piano tends

to loom large at climaxes but this, I suspect, is principally due to

Vierne’s writing rather than to any injudicious balancing by either

Tacchino or the engineers. With informative notes, albeit sometimes

awkwardly translated from the original French, this interesting release

is warmly recommended to any lovers of French music or of chamber music

who wish to explore something a little off the beaten track.

John Quinn