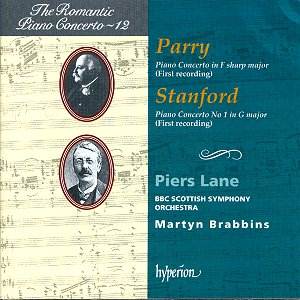

These two works are rarely

heard in the concert hall as is the hallmark of works included in Hyperion’s

Romantic Piano Concerto series.

Although both composers

were of similar age and grew up together their backgrounds were as different

as their compositions.

Parry came from

a family of distinction, was educated at Eton and went up to Oxford

where he made use of the musical opportunities there. His university

studies were Law and History and not music as one might have expected.

In London, Parry acquired a friend in the pianist, Edward Dannreuther

who advised him in his compositions for the piano.

Stanford came from

a Dublin lawyer’s family, and won a Cambridge organ scholarship (Queen's

College) followed by a classical scholarship. He was elected assistant

conductor of the University Musical Society in 1871 and two years later

he became its principal conductor, a post he was to hold for 20 years.

Stanford was appointed organist at Trinity College, Cambridge in 1874

(a post he held until his resignation in 1892). A period of study took

place at Leipzig (under Reinecke and Berlin) but I find this does not

appear to have had any lasting influence on his compositions. As a teacher,

he was an influential figure who taught a whole generation of students

which included Arthur Benjamin, Frank Bridge, Butterworth, Howells and

Vaughan Williams. His music is generally Irish scented.

Parry’s Concerto

opens with a movement containing an unorthodox mix of tonalities. A

ponderous through-composed second movement is languid, and not particularly

memorable. (It has a mechanical ring to part of its structure that tends

to labour an idea, giving little opportunity for piano virtuosity.)

The work wakes up in the third movement with its jaunty main theme and

strong focus on the piano. One can detect elements of Beethoven in the

orchestral scoring. Saint-Saëns (in the third movement) may have

provided a model for some of the pianist-led passages.

Stanford’s Concerto,

by contrast, is lighter and more melodious, holding one’s attention

from the outset with a lively rhythmic flow. There is more colour and

the key is brighter than the Parry (G major). His thematic development

carries one’s interest along with it and there are good virtuoso elements

for the soloist to show off his skills. From the evidence here I would

suspect that Stanford was as much at home with the piano as he was with

the organ.

Piers Lane does not disappoint

with his fine performance, nor Martyn Brabbins in his reading of the

scores. For my liking, perhaps the Allegro maestoso and Maestoso

movements of the Parry are taken a touch too slowly, but both pieces

provide an enjoyable listening experience.

The notes focus more on the soloists who created

the roles rather than the composers’ backgrounds. The recording is warm

(without exaggerated reverberation) and adequately delivers the nuances

in orchestration.

Raymond Walker

Chris Howell has also listened to this release

Try to think, before putting this on, what you might

expect a piano concerto by Parry to sound like. I am willing to bet

that whatever you came up with was very different from the disarmingly

inconsequential opening you will then hear. You are also unlikely to

have imagined that a concerto in F sharp major, at the end of its opening

statement in the home key, will veer suddenly into G major and for much

of its first movement behave like a concerto in G (with a recapitulation

beginning in D). Perhaps you will also not have expected the reflective

second subject, with its melancholy descending phrases and certain sequential

writing later, as well as the dialogue with lush strings, to sound so

much like Rachmaninov (who was eight years old when it was completed).

On the other hand, you may have imagined a piece which sounds like Parry

and I cannot truly say it does.

However, this is an early work, preceding any of the

symphonies (Parry wrote it between the ages of 30 and 32 but he was

a slow developer) and the large canvas is sometimes filled with more

work-a-day passages which detract from this often impressive movement.

And I must say that the opening of the second movement with its organist’s

orchestration and undistinguished material matches only too well some

people’s expectations of Parry. Several grandiose gestures from the

piano cannot really obscure the fact that this movement is a non-starter.

And the finale, in spite of rushing around very busily (and perhaps

containing a few phrases, particularly in the orchestra, which actually

sound like Parry) reaches little beyond its own tail, is far too long

(13’ 45") and contains some really threadbare moments along the

way.

So in the end this proves to be no more than a decent

local product, even if the opening did seem to promise more. Jeremy

Dibble’s notes are rich in information and dedicate more than double

the space to Parry’s concerto than they do to the Stanford. Furthermore

a note by John Farmer, Trustee of Lloyd’s Music Foundation gives a history

of the preparation by Dr. Dibble of the performing edition of the Parry,

telling us that requests for the use of the score have come from America

and Moscow and anticipating "that the work will now find its place

in the international concerto repertoire". So far (seven years

on) this has not come about and I cannot really think it will. Attempts

to export Parry abroad have never had much success, whether in his lifetime

or since and in many ways he is a classic case of a local master.

Stanford, on the other hand, once walked the European

stage and may do so again, even if it is only in his songs that he consistently

matches the finest of his contemporaries. The opening to this concerto,

with a charming theme on the wind heard against arpeggios on the piano,

is entrancing and the first movement contains much elegant and attractive

invention. Unfortunately it also contains some more strenuous passages

which, if Stanford were challenged to say why he wrote them, I don’t

see what he could have replied except "to get from A to B",

thereby diluting the effect. The piano writing itself is effective in

the delicate moments but, as is inclined to happen with a composer who

plays the piano decently but is not a virtuoso, at climaxes he can think

of nothing better to do than storm around in double octaves. I suspect

it is ultimately rather unsatisfying to play, alternating light and

poetic moments with others that don’t deliver all they are meant to.

The slow movement has more substance, a strong and

dignified opening leading to much craggy and passionate development.

The rewriting of the opening theme towards the end is a minor stroke

of genius, reminding us that it is the simplest ideas which affect us

most. The finale opens well but the secondary material is less distinguished,

more like a transition to something more important (which doesn’t emerge)

than a theme in itself. A poetic coda, just before the final pay-off,

does much to redress the balance.

The Stanford concerto which really is a revelation

(at least among those so far recorded) is the First Violin Concerto

(Hyperion CDA67208) while the Clarinet Concerto (Helios CDH55101) has

proved durable and rewarding. The First Piano Concerto is not quite

on this level but it contains much of value, and its eclipse by the

Second Concerto was not wholly just, for the present work perhaps has

a finer slow movement.

It also raises a rather fascinating question. A few

years back I published an article in British Music Society News (no.

75 of September 1997, p. 79 for those readers who have back numbers)

entitled "Stanford and Musical Quotation". I return now to

the subject in so far as it regards this concerto.

In 1889 Stanford had conducted a programme of his music

with the Berlin Philharmonic, including the Fourth Symphony which was

written for the occasion. Brahms, who was present, must surely have

smiled when the first movement’s second subject material contained a

reference to the first of his own Liebesliederwalzer. The First

Piano Concerto was not specifically written for Berlin (it was premiered

in London on 27th May 1895) but Stanford conducted it in

a concert of British music in Berlin on 30th December 1895

and presumably that concert was already planned when he composed the

piece, for the second subject of the first movement of this work

also alludes to the Liebesliederwalzer. It is also fleetingly

quoted towards the end of the finale. Furthermore, the finale of the

Fourth Symphony had a theme which was basically a rising scale. Now,

without the other quotation, I would not make much of the fact that

the second subject of the finale of the First Piano Concerto is also

based on a rising scale, since music is built on scales and it is phrased

and barred so differently as to have a completely different effect.

However, in the context, and bearing in mind that it is at one point

juxtaposed with the Liebesliederwalzer theme, I have little doubt

that this is a further intentional cross-reference.

Just what we are to make of this is not clear. Obviously,

the single works can be perfectly well enjoyed without knowledge of

the quotations. At one level, Stanford was apparently amusing himself

by cross-referencing his music in a way that only he himself and a few

close friends would notice. On the other hand, these references do sometimes

lend point to the music when one has ferreted them out. Somehow this

concerto took on a slightly different meaning for me when I had recognised

the quotations. And this raises the question that Stanford’s work –

of which we after all still know only the tip of the iceberg – maybe

be cross-referenced to an extent we cannot imagine.

The performances seem excellent and the recording good,

if more mellow than brilliant and at a slightly low level.

Christopher Howell

See the Hyperion

Romantic Piano Concerto Series