When Sir Georg Solti and Mother Theresa died at almost

the same moment in August 1997, their deaths were almost totally overshadowed

by the car accident in Paris that claimed the life of the Princess of

Wales and two other people in the car with her. Soltiís obituaries duly

appeared, but the newspapers were so taken up by the other event that

the loss of one of the centuryís leading conductors seemed largely to

go by the board. When other articles did start to appear I remember

being struck by the critical tone of many of them, almost as if the

music press had been waiting for Solti to die so that they could say

what they liked about him. Solti was a pioneer of the gramophone, a

prolific recording artist, and, of course, at the head of the famous

Decca Ring, one of the most celebrated projects of all time.

Yet many commentators took the opportunity of his death to list his

shortcomings, often at the expense of his manifest qualities. The nervous

energy present in most of his work was cited as a weakness; his interpretations

suffered from a certain driven quality, a lack of grace, even of finesse

and subtlety. Well, maybe. But listen to that Ring and see if

you agree. Or the Mahler symphonies, or anything by Bartók. Listen

to Solti in Elgar. With these composers, as with many others, Sir Georg

demonstrated what he was capable of. Not, I rather fear, in Berlioz.

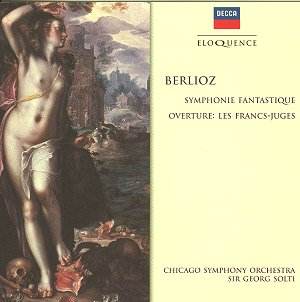

This recording, first issued in 1972, is brilliantly

played by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, but sadly the reasons for

buying it end there. Even the recorded sound is too much of a good thing,

brightly lit to the point of harshness. As for the interpretation, well,

there is little passion or yearning in the slow introduction to the

first movement, still less wistfulness or regret where we might hope

to hear it. And once the main body of the movement is underway the real

character of the interpretation begins to come out even more clearly.

The music is exceptionally hard-driven, with precious little charm or

grace. Accents are exaggerated, and no opportunity to place accents

is missed. Dynamic contrasts are underlined, usually at the expense

of the gentler passages. I donít think Iíve ever heard the second movement

waltz with less lilt, less dancing quality to it, though characteristically

perhaps, the final dash at the end of the movement is well managed.

The Scène aux Champs is so totally lacking in atmosphere

that you wonder how the players achieved it. We may expect the final

two movements to be more successful in that fewer of those qualities

of which the conductor seems short on this occasion are required. And

so it is, even if the Marche au supplice seems rushed, lacking

just the fatal relentlessness that other conductors have been able to

bring to it, and the final witches Sabbath has precious little diabolic

quality to it. The moment when the strings play with the wood of the

bow Ė one of the most hair-raising pieces of orchestration ever, in

my view Ė passes for almost nothing.

Les Francs-juges goes a little better, though

the same qualities, those present and those lacking, are to be noted,

and in any case, even at this price, nobody is going to buy this issue

for the overture.

There are so many outstanding versions of this symphony,

even at bargain price, that this disc, one of the few disappointments

in the excellent Eloquence collection, need not detain us. Try to find

Martinon with the French National Radio Orchestra on EMI for an authentic

French accent, but otherwise any one of Sir Colin Davisís three recordings

(two on Philips, the most recent on LSO Live) demonstrates infinitely

better how subversive and inspired, how varied and sheerly beautiful

a work the Symphonie Fantastique really is.

William Hedley