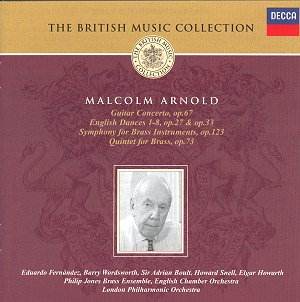

Malcolm Arnold’s two sets of English Dances

are certainly – and deservedly – among his most popular works. Adrian

Boult’s 1954 recording with the London Philharmonic Orchestra (Arnold’s

orchestra) is the earliest one ever available commercially. His was

the first recording of any Arnold work I bought as a teenager and I

still have my literally worn-out copy of that wonderful Ace of Clubs

LP. Boult’s is one of the finest recordings of these beloved pieces

(the finest of all is, I believe, that by Arnold and the LPO on Lyrita),

and its 1954 sound still wears well.

The Guitar Concerto Op.67 (1959), written

for Julian Bream who gave the first performance in Aldeburgh with the

Melos Ensemble (they also recorded it for RCA) is an overt tribute to

jazz and especially to Django Reinhardt. This is particularly evident

in the long slow movement which someone has once described as a script

for a Hitchcock thriller. The most remarkable feature of Arnold’s Guitar

Concerto is that the composer cleverly eschewed all clichés

in his guitar writing, be they Spanish or jazz; and that he approached

his task in his own inimitable way. The scoring for small forces is

a miracle of economy, clarity and efficiency. This is Arnold at his

best and at his most inventive. No wonder that this wonderfully crafted

piece has become a favourite.

The Quintet for Brass Op.73 (1961), actually

Arnold’s first brass quintet (the Brass Quintet No.2 Op.132

was completed in 1987 and is, to the best of my knowledge, still unrecorded

and rarely heard), is also a very popular work that has received many

performances and many fine recordings. Arnold’s unerring flair for brass

instruments is fully displayed in this attractive piece. Has anyone

noticed that the slow movement seems to pay some homage to Holst’s band

piece Hammersmith?

However, the substantial Symphony for Brass Instruments

Op.123 (1978), written for Philip Jones’ fiftieth birthday,

is a quite different piece of music. One might have expected some brilliant

display of brass writing, full of Arnold’s hallmarks; but the Symphony

for Brass is actually a sombre, bleak work and clearly the product

of what has been one of Arnold’s most difficult periods. Though still

superbly written for brass ensemble, the music, while still recognisably

by Arnold, eschews many easy-way-out solutions. It rather evokes a difficult

journey that would reach its ultimate goal in the bleak, unremitting,

uncompromising Ninth Symphony. The Philip Jones Brass Ensemble play

wonderfully as they also do in the Brass Quintet.

In short, this release is most welcome since this recording

of the Symphony for Brass is the only one available so

far. It is good too to have Sir Adrian’s wonderful reading of the English

Dances back in the catalogue.

Hubert Culot