You may have read or heard bad reports about Deborah. But tread

carefully, and be warned: if you give this modestly-priced issue a miss,

you’ll be depriving yourself of some truly wonderful music, expertly executed.

Deborah was Handel’s second oratorio, a failure

(Winton Dean famously but misleadingly declares) sandwiched between

two successes, Esther and Athalia. Composed at a critical

turning point in Handel’s career, when he had all manner of problems

to contend with on the operatic front and the new genre of oratorio

looked likely to be a much better prospect for him, Deborah was

written (or rather put together) at an incredible pace, even by Handel’s

amazing standards: the whole project (from inception to public performance)

was despatched in a couple of months. I say ‘put together’ because the

score relies heavily on earlier compositions: Handel lovers will have

a field day tracking down three of the Chandos Anthems (most notably

O praise the Lord with one consent), parts of the solo cantata

Tu fedel? tu constante?, Dixit Dominus, the Brockes

Passion and Music for the Royal Fireworks, not to mention

‘borrowings’ from Tolomeo, Athalia, Israel in Egypt and Belshazzar.

Samuel Humphreys (who also provided texts for Esther and

Athalia) was responsible for the hastily-concocted libretto,

which makes a rather feeble drama out of the (skeletal, and hardly promising)

story of Deborah in Chapter 5 of the Book of Judges; and he does himself

no favours with his unintentionally humorous rhyming couplets.

As often as not, then, Deborah has been described

(or dismissed) as a pasticcio, with little musical or dramatic

integrity. But it’s nevertheless full to the brim of the grandest and

most memorable Handel: the sum of its parts may be nothing to shout

about, but many of its parts are fashioned from pure gold!

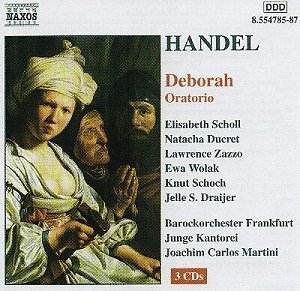

This Naxos team has already given us admirable versions

of Athalia and Il Trionfo del Tempo e della Veritè.

It’s very obviously recorded at a (single and more or less unedited?)

public performance: so you’ll have to forgive a certain amount of stage

and audience noise, one or two blemishes of ensemble – seldom serious,

it is true – and (in Part III especially) some strained and tired-sounding

voices, most especially in the chorus.

Joachim Carlos Martini is obviously a conscientious

and intelligent musician. Like Robert King before him (in the only other

recording currently available, on Hyperion CDA66841/2), he opts for

the overture used in the 1744 revival, as only a continuo part survives

of the original overture. Acknowledging that we cannot be certain of

what the first performance did or did not include, he also picks and

chooses items from the various editions and texts (among them Chrysander,

Bernd Baselt and Robert King himself) available to him.

Without exception, the soloists sing with conviction,

clarity and style. Scholl and Zazzo deserve a particular mention for

their presence and conviction: Schoch is marginally less secure, and

evidently less certain of his English pronunciation. The orchestra uses

original or copied instruments, and seem completely at home in this

music, playing as they do for the most part with polish and dexterity.

Only the chorus seem in any way tested or stretched by this music, but

their flair and obvious enjoyment go some way to making up for their

rough edges. And it has to be said that there is some exceptionally

elaborate music for them to sing here, including some complex eight-part

and antiphonal material in the very best Handelian choral tradition.

The sound is bright, weighty and spacious: despite

the reverberation, textures are mostly clear and words usually discernible.

The CDs are extensively indexed, and the booklet includes a full text.

If you’re a Messiah lover who’s curious about

Handel’s other oratorios, this might seem an odd choice for branching

out: but you’ll not be disappointed if you do so. The same goes for

serious collectors of Handel’s oratorios: buy this, and hear for yourself

just how good Handel’s ‘failures’ are!

Peter J Lawson

See also review by Roy

Brewer