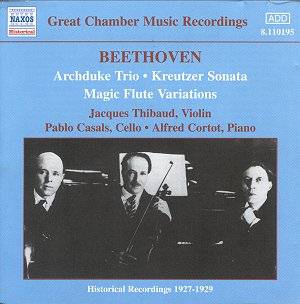

It’s a measure of the paucity of recordings of the Cortot-Thibaud-Casals

trio – itself a direct result of their deliberately limited repertoire

– that this latest release in Naxos’s series has only one performance

by the Trio itself. This all-Beethoven affair presents the Archduke Trio,

supported by Thibaud and Cortot’s Kreutzer and the only recording ever

made by Casals and Cortot as a duo, the Mozart Variations.

The disc begins with the Kreutzer Sonata, recorded

unusually in the Salle Chopin and Salle Pleyel in Paris – the

recording locations changed over the two-day period though there’s no

audible change in acoustic. It’s always been a matter of profound regret

that Thibaud never recorded either the Beethoven Concerto or the Mozart

Sinfonia Concertante – a performance with his superb colleague, the

violist Maurice Vieux, must now remain just a dream – but the Kreutzer

does indicate directions and priorities in Thibaud’s Beethoven playing

from which we may be able to draw reasonable conclusions. His playing,

light, sweet, somewhat small in scale, sits at a somewhat rarefied tangential

remove from the more explosive central European or Russian approaches.

His gorgeously equalized scale is as ever a thing of wonder as is the

faint whiff of raffiné phrasing in the first movement. The opening

statement, for instance, is decidedly withdrawn – there’s nothing of

Huberman’s almost coarse projection, little of Heifetz’s febrile theatricality,

or the gaunt sobriety of many German players. Instead Thibaud avoids

the disruptive implosions that others find in the music though he’s

never immune from the quicksilver changes of direction implicit in it.

There are very occasional intonational problems but Thibaud’s lyrical

impress is always marvellous but for all the manifold felicities – Thibaud’s

elfin and floated tone, Cortot’s tremendously animated left hand in

the Variations second movement, the clarity and purposefulness of the

concluding part of that movement - and for all that the work ends in

conclusive strength there is still something missing of elemental power

and projection.

The Mozart variations are charmingly done by Casals

and Cortot – no balance problems, no disruptive mannerisms, though there

are some scuffs audible in the generally good transfers. The Archduke

features the trio in a performance of almost symphonic breadth. When

Casals re-recorded the work, in 1951 at the Perpignan Festival, he and

his colleagues Alexander Schneider and Eugene Istomin, albeit that they

played the first movement recapitulation, added an extraordinary ten

minutes to the 1929 recording, which already clocked in at over 35’54

minutes – Naxos’ timings are completely wrong when they claim it lasts

29’28. As ever the tonal disparities between Thibaud and Casals are

abundantly and often constructively, creatively part of the special

alchemy that made their recordings so distinctive. As a performance

there are some ensemble lapses but here in 1929 Casals was far less

inclined to linger over phrases, as he was to become, and retains a

gruff and powerful expressivity throughout, with Thibaud’s gorgeous

liquidity and sweetness of tone and Cortot’s agile and decisive pianism

adding their own unique pleasures. It’s true that Casals experiences

small intonational problems in the opening movement but nothing eclipses

the nobility or the trio’s control of the long line, though the extent

of the rhapsodic slow movement is surely questionable. It’s not, in

the end, an unambiguously great performance – even a contemporary performance,

recorded two years earlier by the Anglo-Australian trio of Albert Sammons,

W H Squire and William Murdoch [on Pearl GEM 0044] yields comprehensively

more coherence and tonal congruity, tighter in tempo relationships and

structure. Nevertheless this is still a marvellous opportunity to hear

the Cortot-Thibaud-Casals trio individually and collectively as Beethovenians

of solid accomplishment.

Jonathan Woolf