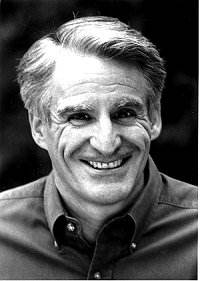

CRAIG SHEPPARD

An Interview by Rob Barnett

|

CRAIG SHEPPARD, LEEDS 1972, with SIR CHARLES GROVES

conducting the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra

photo credit: Judy Tapp |

RB: Craig, can you tell me something about your family

background?

CS: My family have been in the United States for the

most part for eight to ten generations. I am basically of Scots and

English lineage, with some Irish, German, and Polish blood as well.

My parents are both still living – my father is 85, my mother 83. I

will soon turn 55. I have two brothers, one older, one younger. Both

are businessmen.

What form did your early schooling take?

I did ‘normal’ schooling (in the USA, public schools)

through secondary school, whereupon I went to the Curtis Institute in

Philadelphia for three years and then on to the Juilliard School in

New York for another three, earning both Bachelors of Science and Masters

of Music at the latter institution.

Who were your music teachers?

At the Curtis, my teacher was Eleanor Sokoloff (now

88 years old). At Juilliard, it was Sascha Gorodnitzki. I worked privately

with Rudolf Serkin when I was at Marlboro. After my Juilliard years

I worked with Ilona Kabos in both London and New York and Sir Clifford

Curzon in London.

Are there any generic differences between music teaching

in the USA and in the UK or Europe. If so what are they and what do

you put these differences down to?

You know, there might have been differences many years

ago, but today, teachers in this country and all the European countries

are from so many different backgrounds and nationalities that I can’t

believe the differences in generic teaching styles to be that great

from country to country. The reason artists from a particular country

exhibit certain traits would have more to do, in my view, with the general

environment they’ve grown up in, and not their specific teachers.

Can you tell us more about your time with Curzon -

any special insights?

Clifford was obsessive over the most minute details

in a score. This could be exhilarating (as in the Schumann concerto)

or exasperating, as in the Schubert A flat Impromptu. I remember clearly

an entire half hour spent on the first eight bars, chord for chord,

the relationship of each note within the chord to the next, etc.. This

might well have been my most valuable lesson ever, but I begged Clifford

at the end of that half hour to please go on to something else!!

Do you play any other instruments apart from the piano?

I played the clarinet when I was a kid, but very poorly!

Now that being able to play the piano is not regarded

as a necessary social accomplishment amongst the generality of people

has Society lost out, what have we lost and have gained anything?

The environment I grew up in had nothing to do with

this side of things, so I can’t comment.

What were the circumstances of your public debut as

a pianist

The only ‘formal’ debut I ever made was at the Metropolitan

Museum in New York in January, 1972. I suppose one could say that my

debut as a performer went back to the age of 10 with a local orchestra

in the suburbs of Philadelphia (where I grew up). I played the ‘Capriccio

Brillante’ of Mendelssohn.

What was the first professional orchestra and who was

the first conductor you worked with?

When I was twelve, I won two auditions to play with

the Philadelphia Orchestra at their children’s concerts, one out of

doors and one in the Academy of Music in Philadelphia. The conductor

on both occasions was William Smith, for many years the Assistant Conductor

of that orchestra.

What do you consider to be the highlights of your career?

I’ve had many wonderful moments. Working with Aaron

Copland many years ago (doing his Piano Concerto) was certainly one.

We did this both in the United States and at the Proms in London. My

performances with Sir Georg Solti, either in Salzburg, different centres

in England, or Chicago, were other highlights. A wonderful moment was

when I did the Emperor Concerto with the Royal Phil at the Barbican,

conducted by Lord Menuhin. 'My recital at the Berlin Phil in 1999 was

certainly another wonderful moment. The public and the critics responded

most enthusiastically, particularly after the Goldberg Variations. Working

and performing with artists such as Ida Haendel and the Emerson Quartet

has greatly enriched me.

Have you worked with other soloists in chamber music?

In the 80s I played a number of times with Ida Haendel

– a great joy. Mayumi Fujikawa and I also had a duo for several years.

What are your favourite piano concertos and why?

I have many that I love. Contrary to many pianists,

I find the most difficult, and perhaps the most rewarding, to be Brahms

2. Many pianists find the Bartok 2 to be the sine qua non of difficult

concerti, but I do think the Brahms is more so, if only because everybody

knows it better and it’s more transparent in texture. I adore playing

any and all of the Mozart concerti, and the Beethovens certainly have

to be up there, too. It’s fun to play the Rach 3 from time to time –

I had my first successes in the United Kingdom with that piece – but

I can’t say it’s my favorite work.

You have mentioned Rachmaninov’s Third Piano Concerto.

What are your impressions of the First and the Fourth.

I adore the first concerto and played it frequently

when I was younger. Don’t forget that the first concerto was really

Opus 1/39b, having been revised just after the Opus 39 Études-Tableaux

were finished in Moscow in 1917, and immediately before Rachmaninov

went into permanent exile. I have learned the fourth but not performed

it. It has never been one of my favorites (many of my colleagues will

disagree). I think the Paganini Rhapsody is his greatest piano concerto,

without a doubt.

You also mentioned having studied with Serkin earlier

in this conversation. Do you know Serkin’s recordings of Brahms 2 with

the Cleveland and Szell. Any views. What were Serkin’s special qualities?

Yes I do know those, and I love them. In general, though,

I don’t feel Mr. Serkin recorded well. I think even he himself would

have admitted this, judging by a conversation I once had with him at

Marlboro. In concert, he was notoriously uneven. But when it came off,

when he hit the mark, it was truly unforgettable, magisterial, unbelievably

energising. And I think the most important lesson to have been learned

from him was his unrelenting attempt to remain true to the score and

somehow incorporate that larger-than-life personality of his into the

performance. It was really something to experience this struggle.

Do you suffer from nerves before a performance and

how do you handle this?

I don’t really suffer too often from nerves as such,

though I am most certainly geared up inside one way or the other. Otherwise

I couldn’t call myself a performer. And this is true for any venue,

whether it be London, Berlin, or a much more obscure place. But when

nerves have occurred, they can have a near-devastating effect. Perhaps

deep, sustained breathing exercises will help, if one is offstage

when the nerves become apparent. But if the nerves start acting up onstage,

or if one’s hands start shaking for any reason whilst performing (it

has happened), one just has to work through it. There is no easy solution.

It is said of some players that they use stimulants

to enhance their playing …

I often have a glass of wine with dinner, and once

or twice a month perhaps enjoy a scotch. But I never smoke.And I never

ever touch alcohol close to a performance. There are stories

in the profession of famous artists who would tipple before or even

during a concert, but it’s something I simply cannot conceive.

Name some conductors you prefer to work with and why?

Presumably you are speaking of living conductors! Michael

Tilson Thomas has more ideas coming out of him than anybody I know.

It’s always exciting to be with him and work with him. David Zinman

is a marvellous accompanist and musician. I remember many years ago

a wonderful experience working with Jimmy Levine. And I think Leonard

Slatkin is simply marvelous in every sphere.

OK those are the living conductors what about those

who are no longer alive.

Working with Erich Leinsdorf was a thrill. I was only

nineteen at the time and played the Brahms D minor with him and the

student orchestra at Tanglewood. Mr. Leinsdorf was very kind and enormously

patient with me! Solti had a profound influence, perhaps because I was

privileged to get to know him and his family for a period back in the

late ‘80s. I think his unbeatable work ethic is what sticks most in

my memory. Let me give two examples. My (now-ex) wife and I were vacationing

with the Solti’s in their summer house down in Italy and Sir Georg was

about to go off to Paris to do the Bartók Music for Strings,

Percussion and Celesta and Beethoven 3. When he would be studying

one score, I would borrow the other. I noticed that he had written down

in the front page of the Beethoven every single performance and recording

(there were at least three) he had made since giving his first performance

in, I believe, 1947. Yet there he was, out on the lawn with his score,

metronome in hand, making sure that his tempo for the Scherzo was unflinchingly

accurate. Let me tell you that Solti was the sort who could hear the

difference between a crochet at 130 and a crochet at 132 – he proved

this to me when I was preparing the K.491 to play with him and London

Philharmonic. Yet there was this great maestro, checking himself to

make sure that his own reactions to the score remained true and accurate.

On another occasion, we were with the Solti’s in Switzerland and Maestro

was to go off to Vienna a few days hence to record the second act of

Die Frau ohne Schatten. In order to be able to enjoy the

rest of the day with his family and friends, Sir Georg was up at his

desk and at work by six in the morning, cup of coffee in hand, while

the rest of us enjoyed our last moments of sleep. And don’t forget that

he was nearly 77 at the time! Such lessons are something everybody can

learn from.

Have you ever had any performances you now regret?

There have been a few, but luckily these were many

years ago, and I would prefer to forget them if I could! I can say that

they happened almost invariably because I allowed myself to be booked

with too much repertoire within too short a space of time. When one

is young, this is something one relies on a manager to sort out and

prevent, but in my experience, this rarely happens. The artist has to

learn early on how to stand up for him or herself and say ‘no’, even

if such a decision has overtly negative consequences for the immediate

future.

Have you ever taught your instrument to others, privately

or at music college/school and can you name any such pupils who have

'gone on to greater things'? where did you teach and when?

I’m glad you’ve asked this question, Ron, because until

now most of our discussion has been about my public professional life.

Teaching has always constituted a major portion of my time and energy

and focus, now more so than ever, and I’ve always had a large private

studio wherever I’ve lived, be it in Philadelphia, New York, London,

or Seattle. In London, I taught at the Guildhall from 1981 through 1986

and visited the Menuhin School frequently out in Surrey during a ten-year

period from 1978-88, to give master classes, private lessons, and even

a couple of benefit concerts. I also gave master classes at various

times during my twenty years in England at both Oxford and Cambridge

universities. Here in Seattle, I have been on the faculty at the University

of Washington since 1993 and have very gifted students from all over

the world – the Far East, the former Soviet Union, Europe, and South

America, in addition to those born and raised in this country. The nature

of a university is very different from that of a conservatory. The students

are offered a much more thorough intellectual education, which I think

bodes better for our profession in the long run. Incidentally, competition

winners and competitors come to us frequently to take the degree of

Doctor of Musical Arts – over half my students are DMA’s. In addition

to their recitals (there are four), one of the most challenging things

in this degree is the written dissertation at the very end, during which

time the learning curve for me is often as great as for the students.

It is very demanding work, but a lot of fun, too.

You ask about students who’ve gone on to greater things.

In Europe, Nigel Hutchison, Falko Steinbach, and Rachel Quinn have all

gone on to perform widely and to teach. I understand Rachel has just

given a very successful concert in her hometown of Dublin, and Falko

is now on the faculty of the University of New Mexico and has recently

returned from a successful tour in Germany. In this country, Sean Botkin,

who has worked with me privately, is doing big things, and I’m watching

a couple of my present DMA’s to see what will happen – two of them,

in particular, have really brilliant talents.

|

CRAIG SHEPPARD, 2002, SEATTLE

photo credit: Cynthia St Clair |

Any who you have marked down for greater things in

the future

Predicting the future is a dangerous business!

Any subsequent degrees, awards, etc:

My first, and most important award, of course, was

the Silver Medal at the Leeds Competition in 1972. I’m still proud of

this achievement.

What engagements were you offered immediately afterwards

Many things came my way, including the Royal Concert

at the Albert Hall (the only time I ever met the Queen Mum), and a BBC

Television recital.

Who were your co-competitors at Leeds and are you still

in touch with any of them?

Well, of course, the gold medal went to Murray Perahia

that year. Murray and I were good friends, particularly towards the

end of my twenty years in England, and we are still in contact with

each other from time to time. The Bronze medal went to Eugene Indjic,

who I believe still lives in Paris (I recently saw that he had recorded

all the Chopin Mazurkas). One other competitor that year was Mitsuko

Uchida. I remember hearing her Schönberg in the semi-final round

and being subsequently very surprised that she had not been a finalist.

Of course, she won the Silver Medal three years hence.

Can you remind us what you played at the various stages

at Leeds

I did Beethoven Opus 31 No.1, the F minor Chopin Ballade,

and the Étude Pour les arpèges composés

of Debussy in the first round. In the second round, I did both the Liszt

and Bartok sonatas. In the semi-final stage, I did both K.449 (with

the Liverpool Phil) and a recital of the Haydn C minor sonata and Petrushka.

In the finals, I did the Rach 3. The repertoire in those days was very

different from that which Fanny Waterman has now chosen.

What are your thoughts on the life of a travelling

international concert pianist.

I think the life of a travelling artist is not nearly

as glamorous as it must appear on the outside. Very frequently one finds

oneself in a strange city after a concert with nothing to do and nobody

to really talk to. This is mitigated to a certain extent by my love

of reading, but those hours after a concert are so important to wind

down properly, and it’s easier if one has friends and family to help

with this.

Does that life still hold attractions for you?

Indeed it does, and I still travel quite a bit. This

year, in fact, I’ve been to Japan, Taiwan, and on the European continent

to play. I love meeting interesting people and seeing new and interesting

places. This is something I’ll never grow tired of! Beyond that, though,

I am very much a home body and really love the home I’ve created here

in Seattle.

Did the Silver at Leeds really transform your career?

Yes it did, though I found the negative sides of things,

such as intrusive fans, to be almost more than I could bear at times.

How important is the public to you? Do you ever feel

that fan-dom undermines a genuine regard for music?

The collective energy from the public is extremely

important for all performers. I wouldn’t believe anyone who told me

otherwise!! But why and how this energy is important for me personally

has changed somewhat over the years. It will come as a surprise to many

who might have heard me when I was younger that I found it almost painful

to get up after a performance and take a bow. I would much rather have

simply walked offstage unnoticed!! Believe me, it is not false modesty,

but quite simply the way I often felt. You know, when one is fully ‘in’

a piece of music, to suddenly have to relate to the audience at the

work’s conclusion can be very daunting. On the other hand, today I have

a very different attitude, if only because I am very aware of my need

to interact with the audience’s energy, and the audience’s need to show

their appreciation for what I’ve been able to give them. If this sounds

like pie in the sky, then so be it. We are all sharing our gifts onstage,

whatever their merits. If we don’t want to share them, we have no right

to be there! With regard to hero-worship, this unfortunately exists

in every public profession, and I have had my share of it as well. I

don’t like it, but not liking it is not going to change it! Luckily,

I believe most of the audience really is responding to the music.

When and if it is well played, how can they not!

How do you respond to aggressive and negative reviews?

My reactions vary. If the criticism is unduly harsh,

I’m often mad, or hurt, or both. With time, either I realize that the

critic was an idiot, or that he or she was trying to tell me something

that I really needed to learn. There is always a grain of truth in any

criticism. By the same token, I think one should take complimentary

criticism with a bit of a grain of salt as well. What’s most important

is the work that one does before getting up onstage, not what happens

once one is there!

What are your hobbies and spare-time pursuits?

I read a great deal in a variety of mediums, and I

swim a few times a week when I’m in Seattle in an attempt to keep in

shape. I also find swimming enormously relaxing.

What do you consider the most demanding works you have

played and why are they so demanding?

Well, things such as the Rach 3 have a helluva lot

of notes, but I don’t think they are by any stretch of the imagination

the most demanding. As I’ve said before, I think Brahms 2 is the most

difficult concerto in the repertoire. People know every note of it,

and they all have their own conceptions of how they want to hear it.

This might be true of other works in the repertoire, but when you put

the sheer technical and musical difficulties of the Brahms on top of

it all, is makes for an almost impossible task. I remember once one

of my teachers, Rudolf Serkin, telling me that the ‘Hammerklavier’ wasn’t

difficult, it was impossible! Having played it many times, I think I

know what he means. Something, albeit perhaps very small, invariably

goes wrong, and it’s never when you think it’s going to happen! A work

which is terribly rewarding, yet terribly draining, is the Goldberg

Variations, which I’ve performed frequently. I’m sure I could find some

of the so-called virtuoso warhorses in the repertoire to talk about,

many of which I played when I was younger. At the moment my affections

are elsewhere, but I cannot rule out doing them in the future – in fact,

it’s a distinct possibility!

Do you prefer to perform in a live concert or a recording

studio and why?

I generally dislike studio recording. I need an audience

to respond to, and not a ‘dead’ microphone. My playing is always invariably

much better in a live situation.

What artistes do you admire and why?

There are too many to list.

There seems to be a yawning chasm between classical

music and ‘modern’ music. Where do you stand on this issue?

This is nonsensical. There is room for everybody. I

do think Bach is the greatest we’ve ever seen (or heard), but that doesn’t

preclude many great figures since that time, nor from this past century.

Quite to the contrary. Bartók’s music is considered in many circles

today to be almost classic. More contemporary composers will eventually

be better understood, and many will be forgotten, as has happened in

the past. Nothing will change in this regard, I feel.

What other well-known figures do you know or have you

met and how have they shaped your experience?

As I have mentioned earlier, both Sir Clifford Curzon

and Sir Georg Solti had a very profound influence on me when I lived

in London. I knew Sir Clifford well in his last years, and loved him

as an artist and as a human being. I also had the good fortune of working

with Solti on several occasions, and to have experienced that incredible

energy allied to an uncanny ear for anything, be it rhythm, colour,

pitch – you name it – is something that I will always be grateful for.

Do you have any political or religious convictions,

what and how keenly do you follow them?

I do have strong feelings politically, but prefer to

keep them within my four walls. I like to retain my friends! I also

have very deep religious feelings, but once again, they are not for

public consumption.

Which modern composers do you admire and why?

I love Luciano Berio. His wealth of invention is staggering.

I’ve always loved Messiaen, though I haven’t played a great deal, apart

from some chamber works. I have a secret admiration for Xenakis, probably

because I find his works impossibly difficult and yet unbearably exciting.

People sometimes write of music being either cerebral

or emotional. Your views?

How can you separate the two – what is cerebral must

by definition (in my book) also work along with the senses, and vice

versa.

As a performer, what criteria do you employ in playing

any work? How do you strike a balance between realising the composer's

intentions and self-expression?

This is a sticky issue. To be honest, the composer

is dead on that page of music until we, as performers, bring him or

her alive. Any performance of any piece of classical music has got to

be transformed through the performer’s personality in order to be heard.

To what extent we as performers interject ourselves is the real issue.

I see it as a balancing act. One must know and ‘be true to’ everything

which is on the page. Beyond that, one must try and sort out what the

composer was really trying to say at that moment. I know all

too well, having worked with many contemporary composers in the past

thirty-five years, that what they put on the page is more often than

not only a blueprint. More than once, if I’ve changed something, the

composer will say: ‘Yes, that’s fine, because you’ve approached the

‘argument’ (or thesis) of the work from a slightly different angle than

I conceived at the moment I was writing it. So your conclusion is not

only perfectly natural, but also justifiable.’ On other occasions, the

composers have been sticklers for the minutest of printed details.!

So it can work either way. The problem for us performers is with the

so-called ‘dead’ composers. More often than not, the music simply leaps

off the page at me, it speaks openly, strongly, and affirmatively to

me. But how many are the times that I wished I could have rung up Beethoven,

or Bach, or Mozart, or Schubert, and asked them what they meant by a

hair-pin, a sforzato, a pianissimo that seemed misplaced. Such moments

in music are the things that one loses a good night’s sleep over, and

I’m not exaggerating! Having lived with a work for a certain period,

though, I do feel that an honest and conscientious performer has the

right, and maybe even the duty, to change a few things in the score

if it allows that score to come alive in a better way.

Are there any composers that you do not readily respond

to?

I usually find something in every one of them that

I can relate to. Perhaps some better than others.

What things do you find irritating about other performers'

performances of works that you perform yourself?

Whether it be in works that I perform myself or not,

I find incredibly irritating the affected way of music making that is

making the rounds amongst many of today’s younger, and successful, generation.

What I mean by ‘irritating’ is the gross exaggeration of dynamics and

tempi, the sheer lack of regard towards simplicity of movement, thought

and feeling that is part and parcel of any truly great work. Luckily

for all of these great works in the piano literature, there are still

older, more established and more seasoned artists to lead the way. But

it seems that this is what the promoters and the managers think the

audiences really want to see and hear. I’m not so sure…

Who do you consider the greatest composers for your

instrument and why?

I find Bach the greatest of all composers, living or

dead. To paraphrase those old Heineken ads from the ’80s. Bach reaches

the parts the other composers don’t reach!!

How far do you accept the suggestion of exclusively

male and female nature in music?

This I also find nonsense. There is a masculine and

feminine component in each and every human being on this globe. Simply

the mixture is different from person to person, and composer to composer.

One could give unending examples of femininity in the most masculine

of composers, and strength of character (if that be the opposite of

femininity, which it is not) in the most outwardly feminine. I find

that Chopin, in particular, has an iron will. In fact, I am told that

the town where he was born outside Warsaw, Zelazowa Wola, is a old form

of the term ‘iron will’ in Polish. What a coincidence!!

Have you ever found an accompanying conductor unsympathetic?

If they are dead you can name them as examples:

There are several, both dead and alive. I prefer not

giving names!

Do you ever receive unsolicited manuscripts of works

to perform? How do you react and have any been successful?

I have received many such works. I always read them

through, but don’t perform them too frequently, as much from a lack

of time as a lack of will.

How far is it true that if you don't like a piece you

will not perform it?

I have started out disliking a piece on several occasions,

particularly when I was younger, and ended up liking it. So I don’t

always trust my initial reactions!!

Have you written any books or articles?

Not yet.

Have you broadcast any talks?

I have had talks broadcast in England, Germany, France

and the United States, in each case in the language of the country in

question.

Discography:

EMI (Classics for Pleasure) reissued a few years back

an old LP of Liszt Operatic Transcriptions and Paraphrases that

I did back in the 70s. At present there are four CDs produced by Annette

Tangermann in Berlin (tel. 00 49 30 805 5558, fax 00 49 30 806 03063)

at-label@gmx.de. I do not believe

they are distributed in the UK. These include live performances of my

Goldberg Variations from the Berlin Phil (in 1999), as well as

the Beethoven Diabelli Variations coupled with the fifth Scriabin

sonata, the complete Chopin Preludes and the Scriabin Preludes of Opus

11, and some Scarlatti sonatas coupled with the Opus 39 Etudes-Tableaux

of Rachmaninov. The latter were all recorded in concerts I’ve given

over the past several years here in Seattle’s Meany Theatre. A fifth

and sixth CD will be coming out shortly, live performances of Schumann’s

complete Novelettes and Ravel’s Miroirs and Gaspard de la

Nuit.

Your favourite recording (your own playing) and why

The Diabelli is a performance I’ll always be

proud of. It was recently featured on Berlin’s favorite classical talk

show and compared very favourably to a number of recordings by great

artists, both past and present. I am about to launch on a series of

concerts devoted to the complete Beethoven sonatas, which will eventually

be released on both CD and video.

Please list your recordings and give details of how

to purchase them

I’ve listed Annette Tangermann’s phone number and fax

above. Should anyone wish to write to her instead, her address is: Friedenstrasse

16, 14109 Berlin, Germany.

Lessons for young pianists

For any young artist, I would advise to keep an open

and inquisitive mind, read omnivorously from many different sources,

go to a lot of concerts of fellow artists, and of course, practice and

learn new music continually. And be unflinchingly honest to your deeper

self, whatever it be. This is the hardest of all to accomplish.

Any words of wisdom for those who have won distinction

in piano competitions

Try not to allow feelings of a momentary accomplishment

to obscure the need to develop and grow.

What do you consider to be the role of competitions

and how significant are they

Competitions are significant, and can help to launch

a career if that career if ready to be launched (two cases in point

are those of Radu Lupu and Murray Perahia). Otherwise, I can’t see a

lot of merit in competitions and don’t really feel in the long run that

they have a great significance in ones overall growth or life’s path.

Your ten desert island recordings and why?

I would certainly have to take along Peter Pears and

Benjamin Britten doing their Winterreise from 1963. I think it’s

one of the all time great recordings. The Busch Quartet’s recording

of the Opus 130 Beethoven also made a very deep impression on me at

one point in my life. I would certainly have Barabara Hendricks and

Radu Lupu doing Schubert Lieder. And Murray Perahia’s Handel and Scarlatti

CD. And an early recording of Alfred Brendel’s Diabelli (1976).

And Pollini’s Davidsbündlertänze. And Clifford Curzon’s

K.595. Or Edwin Fischer’s K.491. Not to mention all of my old recordings

of Cortot and Rachmaninov. Must I really be limited to only ten?!

Not so very long ago Philips launched a ‘Great Pianists

of the Century’ series. What do you think of such concepts and who would

you nominate as the ten greatest dead pianists?

I think the concept was a good one, though in my view

it wasn’t entirely successful. An arbitrary list of candidates strikes

me as frighteningly difficult. Among the great dead pianists would have

to be Hofmann and Rachmaninov and Cortot and Ignaz Friedmann and Rubinstein

and Horowitz. Going back in time, what about Liszt and Thalberg, or

even Brahms? Or Hummel?

What do you consider to be the advantages of an era

in which recorded sound in classical music has secured the ascendancy?

I think that listeners can become better acquainted

with the music before coming to the concert hall. And in some cases,

particularly with live recordings, they can access again and again a

performance that has really meant something to them.

What are the demerits of that ascendancy?

The demerits are many. People are putting out ‘live’

recordings today that have little bearing on the concerts they actually

performed. So a certain honesty has been lost. I feel that recording

over the past thirty-odd years has caused the listener to want to hear

a generic performance of a given work, with little latitude in ones

imagination for real differences in artistry.

And the greatest living pianists

There are a number whom I regard very very highly,

some of whom are friends. I prefer not mentioning them, for fear of

omitting one or the other.

Have you ever been tempted to write music and if not

why was this?

I have written music, mostly very badly! And the odd

cadenza to a Mozart concerto, with varying results.

For how many days each day do you practise? Is there

a pattern or routine?

My practise routine is usually to try and do three

or four hours every morning. I teach at the university in the afternoon.

One maddening, but necessary, part of university life is all the committees

one must sit on, and these occasionally muck up my morning’s practise!

Do you object to your recordings being listened to

casually, perhaps in the car or while doing the housework?

Not at all. In fact, I’m afraid to admit that I listen

to most of my CDs in the car, if only because that’s the only time I

can be alone and really listen properly. If I lose a bit of the detail

or the clarity, which I don’t think is the case, then so be it. I don’t

ever have music in the background, though – this is one of my bêtes

noires, and I hate it when I am subjected to it in other places. For

example, if I am invited someplace and that person has on a recording

of anything, no matter whether it be classical music or another medium,

my ears are simply trained to go out and listen to it. And God forbid

that this be one of my own recordings!! That puts a strain on the conversation,

and I always ask the person to turn the music off. This has made me

unpopular on more than one occasion!

How do you feel about pirate recordings of your concert

broadcasts?

I have nothing whatsoever against this practise. At

least people are listening to classical music – to me that is far more

important than whether I am getting a royalty or not.

Do you have recordings made of your concerts now and

in the past

I have plenty of cassette tapes and old reel-to-reel

tapes, some of which I’ve had put onto CD for my personal use. I’m not

sure I’d want many of them out there on public display, though! The

best of the most recent performances have been issued by Annette Tangermann

in Berlin, as mentioned previously.

Do you have recordings of your Leeds concerts.

Yes I do, excepting a full recording of the 3rd

Rachmaninov, which I did in the finals. There I only have the video

of the last movement, which is what the BBC aired the night after the

final round.

If time permitted which concertos would you like to

work up for concert performance.

A number of years ago, I learnt both the Schönberg

concerto and the Berg Kammerkonzert (for 13 Winds and Piano).

I love both of these works, particularly the Berg, but have never had

the opportunity to perform them.

What do you want to be remembered for? What do you

think is your greatest contribution to music?

It’s too early to say yet! And I’m not sure that one

ever knows the real impression one is leaving with other people. That’s

for the future to decide.

© Craig Sheppard

30 August 2002

NOTE

As I write this, a friend over in Berlin is building

a website for me that is attached to her agency. It can be accessed

under www.conductor.de . Within

a few weeks, people will be able to access not only the site, but also

listen to snippets of my CDs. CS

………………………………………………………………………………

OUTLINE BIOGRAPHY

CRAIG SHEPPARD gave a series of concerts and

lectures in Japan in June, 2002. He will present the complete Beethoven

piano sonatas in a seven-concert cycle starting the latter part of the

2002-03 Season in Seattle at the Meany Theater. Recently, Sheppard

stepped in on three hours' notice to perform the Mozart C minor

Piano Concerto, K. 491, with Gerard Schwarz and the Seattle Symphony

at Benaroya Hall. In April, 1999, he gave his long-awaited recital début

at the Berlin Philharmonic to great critical acclaim. In 1999, he was

also presented by the Seattle Symphony in a highly acclaimed series

of lecture/recitals at the Benaroya Hall. He appeared with the Seattle

Symphony in 1998 in their inaugural season at Benaroya, and was also

previously featured with the orchestra in the opening concerts of the

1996-97 season at the Opera House, along with the violinist, Midori.

Sheppard has had a high profile in recent summers at the Seattle

Chamber Music Festival, playing the world première of Richard

Danielpour's Songs of the Night among many works from

the standard chamber music repertoire. He also performs regularly at

the Park City (Utah) International Festival, and both teaches and performs

every Summer at the Heifetz International Music Institute in Wolfeboro,

New Hampshire (formerly Annapolis, Maryland).

Craig Sheppard was born and raised in Philadelphia,

and graduated from both the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia and the

Juilliard School in New York. Sheppard's teachers included Eleanor

Sokoloff, Sascha Gorodnitzki, Ilona Kabos, and Sir Clifford Curzon.

He also worked with Rudolf Serkin and Pablo Casals at the Marlboro Festival.

Following a highly successful New York début

at the Metropolitan Museum in 1972, Sheppard won the silver medal

that year at the Leeds International Pianoforte Competition in England.

Moving to London the following year, he quickly established himself

through recording and frequent appearances on BBC radio and television

as one of the preeminent pianists of his generation, giving cycles of

Bach's Klavierübung and the complete solo works of Brahms

in London and other musical centers. During the twenty years he lived

in England, he also taught at Lancaster University, the Yehudi Menuhin

School, and the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, in addition to

giving master classes at both Oxford and Cambridge universities.

Sheppard has performed with all the major orchestras

in Great Britain, as well as those of Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago,

San Francisco, Atlanta, Dallas, Seattle, Buffalo and Rochester, among

others in the United States, and with such conductors as Sir Georg Solti,

James Levine, Leonard Slatkin, Michael Tilson Thomas, Sir Andrew Davis,

Lord Yehudi Menuhin, Erich Leinsdorf, Kurt Sanderling, Neeme Järvi,

Hans Vonk, Aaron Copland, David Zinman, Gerard Schwarz and Peter Erös.

Sheppard's repertoire is extensive, encompassing

over forty solo recital programs and sixty concerti. In the past several

seasons, his recitals have included the complete Études of Chopin,

Rachmaninoff, and Débussy, and Beethoven's 'Hammerklavier' and

Opus 111 sonatas. His work with singers such as Victoria de los Angeles,

José Carreras, and Irina Arkhipova; trumpeter Wynton Marsalis;

and ensembles such as the Cleveland, Bartok, and Emerson string quartets,

has constituted an important element in his musical life.

Sheppard has recorded on the EMI (Classics for

Pleasure), Polygram (Philips), Sony, Chandos and Cirrus labels. Four

CDs, all of live performances - including his Berlin performance

of the Goldberg Variations, Beethoven's Diabelli Variations

plus the Scriabin Fifth Sonata, Chopin and Scriabin Préludes,

and Scarlatti Sonatas coupled with the Opus 39 Études-Tableaux

of Rachmaninoff - have recently been issued on the label AT (Annette

Tangermann)/Berlin.

Sheppard has appeared on numerous national and

international piano competition juries. He is well known for his broad

academic interests, particularly foreign languages. He is presently

Associate Professor of Piano at the School of Music of the University

of Washington in Seattle.

see conductors web-site

run by Isolde E Ruck

see also CD review