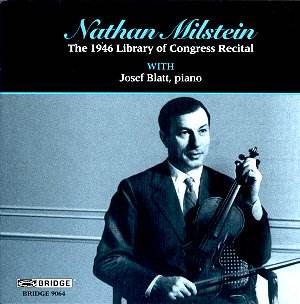

Two Milstein recitals from The Library of Congress

have been issued by Bridge, documents of value and significance. This,

the earlier, dates from 1946 and is a programme of the Old School with

the Vitali Chaconne and a Milstein speciality, solo Bach, sharing space

with a piano accompanied Mendelssohn Concerto and some scintillating

morceaux. The later 1953 recital is a standard post-War Sonata programme

– Beethoven op 24 and Brahms op 108 along with the Bach Partita in D

Minor. In a sense then this brace of recordings documents the changing

patina of the violin recital as it moved from the predictable but still

relatively elastic traditions of Baroque opener, Romantic Concerto and

lighter sweetmeats to the heavyweight three Sonata line-up.

The 1946 recital found Milstein in his early forties

and approaching his peak. Though his longevity – almost unique amongst

violinists in retaining sovereign technical command into his eighties

– has served to elongate and extend his career the forties saw his real

emergence into a position of international eminence. Nominally an Auer

pupil, he had first studied with Oistrakh’s teacher, Stolyarsky, but

Milstein was characteristically contemptuous of his teachers and seems

to have been, to a degree, self-taught. A mutual antipathy also bedevilled

some of his Concerto engagements in which Milstein could duel unceremoniously

with a conductor he despised, a trait he shared with Heifetz. As his

colleague and admirer Piatigorsky remarked Milstein’s natural metier

was solo Bach and after that a Sonata recital with an alert pianist.

In 1946 Milstein was partnered by Joseph Blatt, Viennese born in 1906

and Milstein’s junior by a few years. Composer, conductor, administrator

and pianist Blatt is too distantly recorded and has too little to do

to prove his musical value; he provides staunch if not especially imaginative

or quicksilver support.

The recital begins with the Vitali. There are some

scuffs on the discs but the sound here is generally good. Milstein is

attentive to dynamics but unusually for this stellar musician small

patches of poor intonation intrude. Blatt is lumpy as well and the performance

rather limps along, not yet fully warmed up, with the violinist cool,

pressing ahead somewhat unflinchingly, and to be frank, sounding only

superficially engaged. Low-level rumble/hum afflicts the Bach but if

you can listen past that – and it’s quite possible – you will be rewarded

with a performance that gains in stature the more it develops. He is

a little stiff still in the second movement fugue but the Siciliano

has all the expected Milstein virtues and the presto finale is magnificently

accomplished. His own outrageous and disgraceful Paganiniana is enormously

entertaining and boldly delineated with some slashing attacks whereas

his lyric persuasiveness is exemplified by another of his arrangements,

this time the Chopin C Sharp Minor. The Wieniawski demonstrates a cast

iron technique and an invincible musicality. The piano-accompanied Mendelssohn

Concerto sits at the heart of the recital. As I said this is an example

of days when the Concerto literature was routinely presented in this

way by soloists to audiences, many of whom would never otherwise have

heard them; indeed by soloists who may never otherwise have found many

opportunities to play them with an orchestra. In the opening movement

we can appreciate Milstein’s subtle bowing and rubato, his limited but

expressive portamanti – though I think it would have been better if

Bridge had edited out the audience applause, vigorous and enthusiastic,

after the movement’s end. The slow movement sounds rather unrelieved

however, finger intensity from the violinist aside, and whilst it is

again more than instructive to hear the nature and complexity of his

vibrato usage and how he transmits lyric intensity through dynamic shadings,

there is still rather too much insistence not helped by Blatt’s rather

leaden contribution. The finale goes reasonably well but it’s not a

performance commensurate with the best of Milstein’s admittedly outstanding

Mendelssohn.

Whilst uneven interpretatively and in inconsistent

sound – hums, rumbles, scuffs, bumps, nothing majorly problematic though

– these are performances that both expand and reflect upon Milstein’s

existing commercial discography. At their best they show us how, of

all the Auer or putative Auer pupils, he was the leading Bach player

and quite probably the most complete and impressive chamber player.

As such this disc, and its companion, Bridge 9066, is full of enlightenment

and interest.

Jonathan Woolf