|

|

Search MusicWeb Here |

|

|

||

|

Founder:

Len Mullenger (1942-2025) Editor

in Chief:John Quinn

|

|

|

Search MusicWeb Here |

|

|

||

|

Founder:

Len Mullenger (1942-2025) Editor

in Chief:John Quinn

|

|

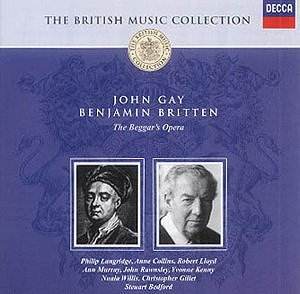

John GAY (1685-1732) Benjamin

BRITTEN (1913-1976) |

|

AmazonUK AmazonUS |

|

Decca’s reissue of the Gay-Britten Beggar’s Opera has dispensed with the valuable notes that accompanied its original appearance and instead gives us just the bare synopsis of the plot. This shouldn’t deter those who have yet to experience this arrangement first performed by the English Opera Group in 1948. Performances since have been sparse and other realisations have taken their place on disc to dilute interest in Britten’s genuinely fruitful exploration of the theatrical life of the Beggar’s Opera, and one which can rightfully now be seen to take an assured place in Britten’s musical development and not, as was once the case, as some kind of kitsch jeux d’esprit. As for those other performances the unvarnished "original" Beggar’s Opera comes from Jeremy Barlow on Hyperion; Richard Bonynge, also on Decca, has a stellar cast. But this first recording, directed by Steuart Bedford receives in almost all respects a performance of vigour, intelligence and wit. Britten’s technique keeps the ear constantly engaged, spicing the work with piquant turns of phrase and intriguing sonorities; the sheer variety of means available to him to spice the score is considerable, whether harmonic or rhythmic and the joy is that so much is so alive and endearing. |

|

Return to Index |