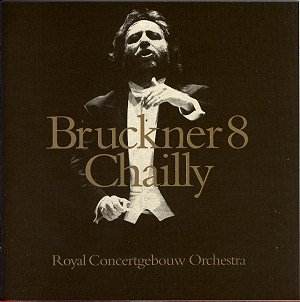

If a work can persuade me to take Bruckner completely seriously

as a composer, itís the 8th Symphony. Donít misunderstand me;

there is much that is great and beautiful in the other symphonies, but

the 8th seems a convincing totality, where the dimension and

character of the four movements balance and complement each other in a

way that doesnít seem to happen elsewhere in the same satisfying way (though

for obvious reasons, the 9th Symphony stands outside this discussion).

It does, though, make huge demands on conductor and

orchestra. The former needs the ability to deal securely with the myriad

ensemble problems that occur while still keeping an eye on the distant

goal and the big picture; the latter need an inner sense of unity that

is so secure that it makes the huge textures work like chamber music.

In the Concertgebouw Orchestra, we surely have that here; hearing them

this week at the Proms, I was struck, as ever, by the flawlessness of

the playing, but much more by the sheer musicality that they

display at all times; nothing narcissistic or superficially sensation-seeking,

just musical honesty at the highest level. That was in Mahlerís 3rd

Symphony, but this symphony calls for many of the same virtues, the

3rd being arguably Mahlerís most Brucknerian work.

Ricardo Chailly wasnít on the box that night, having

injured his shoulder; Eliahu Inbal deputised ably, and, given that he

arrived 25 minutes or so before the Prom started, and had no chance

for rehearsal with orchestra, soloist or choirs, the performance was

near-miraculous. However, I very much regretted Chaillyís absence, never

having seen and heard him conduct live. And he certainly shows here

that he has a real feeling for the music of Bruckner. The symphony is

full of wonderful touches of scoring; Bruckner is more attentive to

his woodwind than usual, and all the detail is heard with wondrous clarity.

The great first movement hangs together superbly, and the massive central

and culminating climaxes are built up with a secure dramatic as well

as structural sense. Here, though, the name of Karajan has to crop up,

indicating that this performance is to be judged by the highest of standards.

Where does Chailly fail, where Karajan succeeds? Well, to me itís not

a matter of failure but of degree; Karajan seems to create an even greater

sense of catastrophe and conflict. There is a tangible sense of evil

forces at work in both of his versions that I am familiar with. As the

trumpets are left repeating the main themeís rhythm near the end of

the movement, Karajan gets them to articulate the rhythm with such vicious

clarity, full of spite and menace. Chailly seems tame, polite even,

compared to this.

The Scherzo is done superbly here, with tingling

string tremolando, and tight yet swinging rhythms. The great Adagio

brings a point of interest at the very start; Bruckner sets up a

quietly throbbing string accompaniment in second violins, violas and

basses, over which he introduces his plangent main theme in the first

violins. The accompaniment figure is usually played so that the actual

rhythm is quite indistinct, acting as a mere carpet of sound on which

the melody can tread softly. Chailly, unusually, articulates the rhythm

with clarity and some weight. I found this wonderful, as it emphasises

the heavy-hearted emotions, and a sense of fatefulness too. Chailly

moves the music on, never lets it languish or over-indulge, with the

result that it moves inexorably toward the clinching climax at around

20:15 (track 3). It should be said that there is the one and only ragged

moment of ensemble here, where a couple of harp notes ring out awkwardly

at the sudden cut off. Maestro Chailly would probably point to the score

and say "Itís what he wrote!", to which I say "Fair enough;

but itís your job to make it work, and I donít think it quite does!"

The coda is sublime in its tranquillity, though a slight

engineering balance problem emerges here, which is more troubling still

in the finale, which is to say that the Concertgebouwís horn section

seems just slightly undermiked. We can here them quite clearly, but

they seem very Ďdeepí. In some passages in the finale, they seem slightly

at odds with the quartet of Wagner tubas, with whom they share some

gorgeous moments. An amateur musician friend commented that he thought

the horns and tubas were Ďout of tuneí at 2:48 (track 4). They arenít

in point of fact, but the perspective is all wrong, which creates much

the same net effect.

This is a very fine Bruckner 8; if not the best available

Ė that accolade probably belongs, according to taste, to one Karajan

and the VPO Ė this is certainly a highly impressive reading, with gloriously

confident and stylish orchestral playing.

Gwyn Parry-Jones