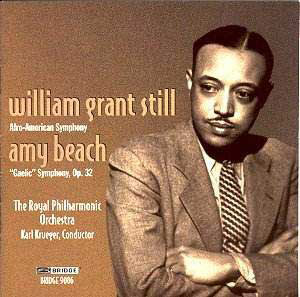

William Grant Still’s experiences in Memphis, writing

band arrangements for W C Handy’s orchestra and subsequently for Eubie

Blake (where he also played the oboe) seem to have been as formative

and formidably productive as his studies with Varèse and Chadwick.

Composed in 1930 whilst he was still involved in arranging and orchestrating,

the Afro-American Symphony is an immediately attractive and expressively

scored work in four movements.

Opening with tightly muted trumpets Still employs the

black vernacular of the Blues – or a species of it – imbedded in an

orchestral sound world which in the opening Modearto assai is spare,

rather impressionistic, with subsidiary harp passages adding a Gallic

taste to the musical argument. Still’s stated purpose was to show how

the Blues "could be elevated to the highest musical level";

to this end he introduces a variational section in the first movement

followed by an expressive theme played on his own instrument, the oboe,

in the form of a spiritual. The slow movement – superscription Sorrow

– is again in sonata form, once more with oboe lines prominent,

some Delian lines flecking the score, textures augmented by bass clarinet,

for which he writes well, harp and that oboe’s continuing sinuous progress

and by some massed bluesy strings. The short third movement – an animato

– is certainly a jaunty affair with its tenor banjo ringing out Showboat-style

and adding a rather Plantation Club feel to the affair. The movement

seems to play with musical stereotypes adding hints of raunchy syncopation

and the "Red Indian" motifs so beloved in the clubs and societies

of contemporary New Orleans. The finale, Aspiration, begins as

a harmonized gospel tune with deep cellos and harp arpeggios adding

more emphatically phrased material, out of which a sonority of twilit

nobility emerges, stripped of extraneous clutter (is that a spectral

vibraharp augmenting the string lines?) The plangent oboe and bass clarinet

still manage to "speak" their songs, as the music seems to

wind down before, suddenly, bursting into renewed life for the short

final section. This is a string-laced spiritual, lashed with cross currents

of brass and, relatively discreet, percussion.

If Still’s Symphony was, to an extent, the embodiment

of Dvořák’s dictum that America should

look to its plantation and minstrel songs, or at least to its black

American music, Amy Beach sought inspiration in the heritage of the

folk songs of Britain and Ireland. Her Gaelic Symphony,

written thirty-four years before Still’s is the Bardic Symphony to end

all Bardic Symphonies. It opens in heroic style, rich in chromaticism

and mountain top horn calls before the second movement introduces the

song The Little Field of Barley – a beautiful tune, simply voiced

by Beach, repeated on the oboe with delicate woodwind accompaniment.

The light brown strings lead to a pizzicato episode and skirling fiddles

that frolic over the tune’s increasing development. It’s the third movement

in which much of the greatest power of the symphony resides. Beginning

powerfully it relaxes into the slow tread of returning pizzicati to

uncover folk melodies anew. It rises to more romantic peaks in the central

panel of the movement with its nourishingly rich violin solos and ends

in a kind of twilight gloaming, underpinned by the percussive tap, burnished

strings, winding woodwind and final, dying violin notes. The finale

reveals its debt to the central European Romantics – Schumann principally

– and does so in a rather martial way, followed by free flowing romanticism

that builds up to a forceful peroration and ends the Symphony in some

powerful splendour.

The recordings are well over thirty years old and they

sound splendid. Notes are good, in English only, and the music of these

profoundly different composers makes for constructive parallel appreciation.

I enjoyed both immensely and all praise to Bridge for this reissue.

Jonathan Woolf