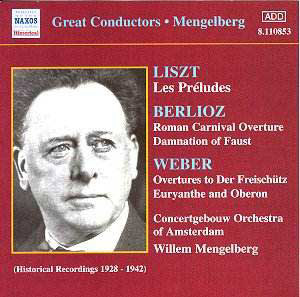

A well-chosen selection of concert overtures is the

spine of this latest installment on Naxos’ Great Conductors series.

The recordings cover the years 1928-42, though this means, specifically,

one Columbia session in 1928, another in 1929, and a final one in 1931

followed by the two Telefunkens of 1937 and 1942 (in both cases of Berlioz).

As ever with Mengelberg there is drama and theatricality in profusion,

colour and intense rubati, uniform portamenti and a highly individual

and personalized approach to form – all of which, needless to say, is

fascinating if not always, to the purist, convincing.

Der Freischütz has an elastic sense of narrative,

plentiful rubati and rich lower strings at 7.25 whilst in Euryanthe

Mengelberg conjures overlapping string lines and indulges little agogics,

intensely theatrical and dramatic. He demonstrates a real sense of paragraphal

conducting, encouraging a lighter weight of string tone and conjuring

up evocative pictorialism – basses of real amplitude and puncturing

brass. Naturally this approach involves departures from pulse and line

but it is intensely fresh and exciting. Oberon opens with an evocative

somnambulant air but there is a thrilling immediacy to his subsequent

fortissimi, well captured in the Concertgebouw in 1928, which defies

objection. His Scherzo from Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream

is superfine and astoundingly fast; it makes Toscanini’s contemporary

recording sound positively lumpy. You’ll love it or loathe it. In the

Carnival Romain Mengelberg achieves elegance rather than forceful

declamation; with strong rubati and mellow strings he is more pliant

than de Sabata and less conclusive than Beecham – a subtle reading,

not at all swashbuckling and self-aggrandizing though not without power

and excitement either.

For the excerpts from The Damnation of Faust he conjures

up a magnificently spectral atmosphere for the Will-o’-the-Wisps whilst

The Dance of the Sylphs are accompanied by a true galaxy of string slides

– most instructive to hear Mengelberg’s unashamed expressivity intact

in 1942 and in the Hungarian March his accelerandos are fearsome and

powerfully exact. Which leaves his incandescent Les Préludes

of 1929. The trumpet rings out thrillingly, cellos and violas play with

pliancy, the burning basses coruscate, the syntax of the work is certainly

stretched taut by Mengelberg but triumphantly so. This defiant and magnificent

1929 recording sounds ringingly triumphant in Naxos’s restoration; in

fact the whole disc does. Ian Julier’s notes strike his usual intelligent

balance between fact and judgement. Exciting, revivifying stuff.

Jonathan Woolf