The two biggest items on this well-filled disc are

the Piano Quartet and Violin Sonata. Both works have been

well served in the record catalogue, with one of the main rivals being

from Chandos’s Walton Edition, a disc that couples these very two works.

It features (among others) violinist Kenneth Sillito and pianist Hamish

Milne, and the performance has a warmth and intensity that are compelling.

There are also notable bargain issues of the Quartet from Naxos

(Peter Donohoe and the Maggini Quartet) and the Sonata from ASV

Quicksilver (Lorraine McAslan and John Blakely), both well worth seeking

out. Having said all that, I can’t help feeling that this superb Hyperion

disc will have great appeal both for the general collector and the Walton

specialist, given the commitment of the playing and the inclusion of

valuable fillers.

The youthful Piano Quartet, admittedly revised

in the ’70s but basically the product of a precocious 16 year-old, here

gets a performance that, to my ears, strikes the perfect balance between

dramatic incisiveness and lyrical warmth. That the young Walton was

already a pragmatic businessman there is no doubt; he was inspired by

the success of the Howells Piano Quartet of 1916, and the shadow

of the older composer is readily discernible in places (try 5.38 into

the first movement). There are also hints of Ravel (the String Quartet

and Piano Trio), as well as the rhythmic zest of Stravinsky.

This performance brings out all these qualities, as well as making us

equally aware that, even at this astonishingly young age, Walton was

very much his own man. The exuberant bite of the scherzo strikes me

as pure Walton, the sort of writing that was to become one of his hallmarks

in the famous later works. Though the players here are a real team,

special mention must be made of Ian Brown, whose superb musicianship,

which has served we collectors for so many years, is again very much

in evidence.

The Violin Sonata can seem a disjointed work

in the wrong hands, but here it emerges with delicious wit and spontaneity.

I have to admit to being an admirer of the ASV McAslan performance mentioned

above, but this is no less persuasive, and is in fact recorded in a

much more pleasant acoustic. The interval of the rising seventh, a real

Walton ‘thumbprint’, dominates the first movement. Marianne Thorsen’s

sweet-toned violin makes us at least as aware of the lyrical yearning

in this phrase, as well as the bitter-sweet pungency. The theme and

variations second movement has an angular chromatic quality that hints

at serialism, though it remains a mere hint. The players here display

real bravura, and the presto finale is truly thrilling.

Anon in Love, the wittily titled Elizabethan

conceit for guitar and tenor, is a setting of six anonymous sixteenth

and seventeenth century lyrics on the subject of love. It was originally

written for Pears and Bream, who also recorded it. John Mark Ainsley

has programmed it regularly, and has recorded it previously for Chandos’s

Walton Edition, with Carlos Bonnell on guitar. I am not familiar with

that recording, but I can’t imagine it being any better than the present

version. How Ainsley and Ogden enjoy themselves in such titles as I

gave her cakes and I gave her ale; there is maybe an unforeseen

allusion to Walton’s own notorious exploits in the delicious setting

of To couple is a custom, which is delivered in a way

that perfectly taps into the wit and point of the setting. The above-mentioned

Chandos disc also happens to include the piano arrangement of the Valse

from Façade, whose fiendish difficulties here stretch

Ian Brown’s technique to the full. He certainly conveys the charm and

’20s nonchalance with consummate skill and flair.

What a different world is evoked in the Passacaglia

for solo cello, written for Rostropovich (who else?) right at the end

of Walton’s life. The sombre theme and ten variations have great power

and eloquence, qualities that emerge in Paul Watkins’s excellent interpretation.

One may miss the sheer outsize personality of the Russian, but the unforced

restraint and control displayed by Watkins pay ample dividends. Walton

packs a lot of variety into a remarkably short (6 minute) span, and

Watkins’s sheer grip and concentration do not let the listener go until

the very end.

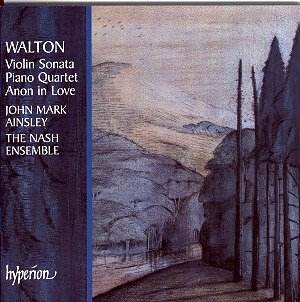

The booklet note by Andrew Burn is a model of its kind,

concise, helpful and very readable. The warmly resonant recording captures

the difficult combinations well, with no false highlighting. Even the

artwork reproduced on the booklet cover is appropriate, being by Paul

Nash. It becomes harder to criticise Hyperion issues, and this is no

exception. For generosity of playing time, thoughtfulness of programming,

and quality of playing and presentation, this is well nigh unbeatable.

Tony Haywood