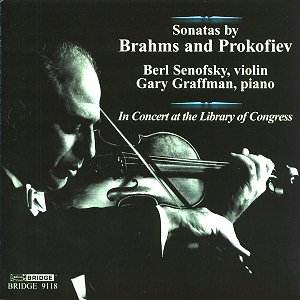

Berl Senofsky, who died very recently, was born in

Philadelphia in 1925. Of Russian émigré stock – his father

had studied with Leopold Auer – Senofsky studied with the dean of American

teachers, Louis Persinger, and subsequently with Ivan Galamian at Juilliard.

He came from a remarkable generation of American born players – his

contemporaries included Oscar Shumsky, Sidney Harth, Aaron Rosand, David

Nadien and the slightly younger Joseph Silverstein. Between 1950 and

1955 he was Assistant Concertmaster of the Cleveland Orchestra under

George Szell. Next to him in the leader’s chair sat Joseph Gingold.

Senofsky sensationally became the first American winner of the Queen

Elizabeth Violin Competition in Brussels – beating, in the terminology

of such things, no less than the superb Russian player Julian Sitkovetsky

as well as such well-known violinists as Viktor Pikaisen and Alberto

Lysy. He began to appear with leading orchestras, toured the Walton

Concerto with the composer conducting during an extensive Australasian

tour – a superbly deadpan colour photograph of the two men arm in arm,

encumbered with pipes, is reproduced in the booklet – and a strong career

beckoned. Somehow it never quite happened for Senofsky despite a few

discographic triumphs. The Brahms Concerto with the Vienna Symphony

under Moralt on Epic both underlined his solid position on the European

continent and ironically reflected the pattern of an earlier recording

of another leading American player, Albert Spalding, who had, towards

the end of his career, also recorded Brahms in Vienna.

With Graffman, his partner at this Library of Congress

recital and whom he’d met first in 1952, he set down the Brahms Op 87

Trio and Beethoven Kakadu Variations – with cellist Shirley Trepel –

in 1965, in addition to their earlier 1961 disc pairing the Debussy

Sonata of 1917 and the Fauré No 1. Elsewhere he appears but rarely

on disc, emphasising the importance of this 1975 survival. He did record

the Brahms No2 and Strauss - with Vanden Eynden on Phonic, as well as

sonatas by Branco and Goldman but these were on obscure labels and all

but invisible. Currently some CDs on the Cembal d’amour label are devoted

to off-air performances and a tape of his prize winning 1955 Queen Elizabeth

Debussy has circulated. In his later years he turned more and more to

chamber music and to teaching – he was at Peabody for many years and

a greatly admired figure.

For the Brahms Sonata, rather airlessly recorded, the

two men begin in appropriately interior fashion; their ensemble is good,

with Graffman perhaps a little too prominent in the balance. This is

a relaxed and unhurried interpretation with Serofsy’s trademark fast

vibrato prominent. In the first movement there are moments when he sounds

as if he is having some problems with his right arm and whilst his attacks

and accents are bold and strong they can also coarsen somewhat under

pressure. The second subject of the slow movement is very deliberately

phrased with Graffman italicising the piano writing rather too broadly

for my liking and Senofsky, though a tonalist of distinction, can be

rather portly and stolid in passagework. He certainly doesn’t convince

me at this somewhat distended tempo and whilst his lyric intensity can’t

be doubted the ardour is rather hobbled here. He commands a wide range

of shadings and colours even with his fast vibrato – an idiosyncratic

one not always easily suited to romantic music – and in the finale employs

some succulent intensification but whilst the depth of tone he elicits

is good there is a real lack of necessary momentum from both men that,

for me, sabotages the performance.

The Prokofiev is rather better. Graffman is idiomatic

and technically adroit infusing his part with manifold skill and insight.

The opening Andante assai sees Senofsky poised and vigorous with no

loss of subtlety. He is powerfully energised in the fiendish Allegro

brusco second movement, a few patchy moments apart – especially expressive

from 5.50 and in the slow movement Senofsky, muted, whilst hardly a

match for Oistrakh, exemplifies why he was so admired with some burnished

playing. Their ensemble, with those tempting, teasing accents and rhythmic

dislocations in the Allegrissimo, survives scrutiny – Graffman releasing

left hand accents with insouciant address. As the movement draws to

a close Senofsky’s vibrato becomes more problematically oscillatory

but it is attractively scaled and a worthy reminder of his art.

The disc concludes with a stage-announced performance

of Brahms’s Sonatensatz, a good performance. Altogether this is an admirable

tribute to a fine violinist. With Graffman he had a collaborator of

instinctual understanding and if neither of the major performances are

world shattering they still shed serious light on Senofsky’s artistic

profile and that is entirely right and proper.

Jonathan Woolf