With the passing of time, and the greater focus on

the feelings of the individual in the intellectual aftermath of the

French Revolution, the developing romantic impulse gave the composition

of lieder a greater priority. And in the longer term still, Schubert's

output of more than six hundred songs established both a repertoire

and an artistic frame of reference. Later composers built upon, and

sought to emulate, his achievement, though none has ever surpassed it:

Schumann, Brahms, Liszt, Wolf, Mahler, Strauss ...

Beyond the huge number of wonderful individual songs,

Schubert also confirmed a new genre that had begun just a few years

before with Beethoven's An die ferne Geliebte (1816): the song

cycle comprising a series of songs on a common poetic theme. Schubert's

two celebrated examples of the genre, Die schöne Müllerin

(1823) and Winterreise (1827), are based on the poetry of

Wilhelm Müller, Imperial Librarian in the Academy at Dessau. In

October 1815 the poet had written: 'Courage! A kindred soul may be found

who will hear the tunes behind the words of my poems, and give them

back to me.' That kindred soul was Schubert but, alas, Müller died

shortly before the completion of Winterreise.

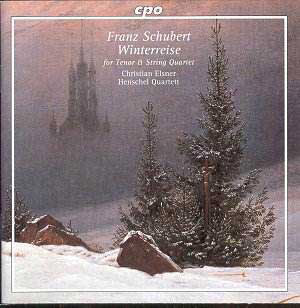

Winterreise was conceived, significantly, for

a duo combination of voice and piano. The present arrangement with string

quartet and tenor was the brainchild of the singer, Christian Elsner,

and there is no question of either his or the Henschel Quartet's commitment

to the cause. Nor is the arrangement by Jens Josef lacking in either

skill or taste. The recording is of excellent quality, so too the general

presentation by CPO. So far, so good. But can the disc be recommended?

The answer is a qualified 'no'. For the essence of

this music is so bound up with the original concept, the more so in

an extended cycle than an individual song, that to rearrange it is to

assault its special nature. Not that others have not previously tried,

including a well known mixed ensemble version by Hans Zender. But the

present release is more likely to be of interest and value to Schubert

aficionados; that is, to those who know and love the music already,

and want to explore other approaches to it.

Christian Elsner is a talented singer and his vocal

qualities do bring insights and satisfaction to this great work. But

the combination of voice and string quartet does not work anything like

so well as the combination of voice and piano. Too often the results

are bland, or pizzicati are forced to substitute for a clear rhythmic

impulse. To be sure, there are plenty of effective moments, for example

the rich toned cello beneath the ensemble in 'Erstarrung', the

muted timbres accompanying 'Rast' (perhaps the highlight of the

performance). However, these points of interest merely serve to underline

how wonderful is the piece in its original form as one of the greatest

achievements of Schubert's miraculous yet tragically short life.

Schubert's friend Josef von Spaun described the scene

late in 1827 when Schubert first presented Winterreise to his

friends and supporters: 'Schubert had been in a gloomy mood for some

time and seemed unwell. When I asked him what was wrong, he would only

say, 'Now you will all soon hear and understand. I shall sing you a

cycle of frightening songs, which have taken more out of me than ever

was the case before.' We were taken aback by the dark mood of these

songs, but Schubert said, 'I like these songs better than all the others

and you will like them too.' And he was right; we were soon enthusiastic

about the impression made by these melancholy songs, which Johann Vogl

sang in a masterly way.'

There is no question that Schubert's commitment to

this cycle of twenty-four songs had everything to do with his own personal

crisis, particularly the intensifying illness which would kill him the

following year at the age of just thirty-one. The project dominated

his artistic priorities, and its true rewards as a work of art remain

in the duo format that Schubert originally conceived. Imitations may

be interesting, but they do remain imitations. Why bother, when it is

possible to visit and revisit the real thing?

Terry Barfoot