|

|

Search MusicWeb Here |

|

|

||

|

Founder:

Len Mullenger (1942-2025) Editor

in Chief:John Quinn

|

|

|

Search MusicWeb Here |

|

|

||

|

Founder:

Len Mullenger (1942-2025) Editor

in Chief:John Quinn

|

|

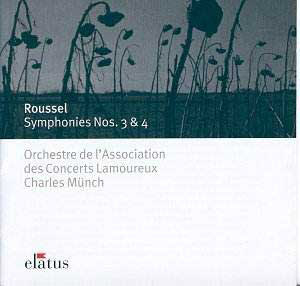

Albert ROUSSEL (1869-1937) |

|

|

|

This new budget Elatus release has two immediate things in its favour - the price, and Munch’s blazingly incandescent conducting. That said, there are down sides. The recording is reasonable, but certainly not in the top flight, with a rather boxy acoustic and congested climaxes. The orchestral playing is also suspect in many places, mainly due to Munch’s tempi, which are excitingly brisk but stretch the strings beyond their limits. The playing time is also miserly, even for budget price. At least one more substantial item could have been fitted in, if not a whole symphony then one of Roussel’s many individual orchestral pieces. I mention this because it does become an issue when weighing up the competition. One of this disc’s main rivals will undoubtedly be the super-budget twofer from Ultima, which features Charles Dutoit and the French National Orchestra performing all four symphonies in a neat package and digital sound. At full price from Chandos one can get Järvi and the Detroit Symphony giving us Symphonies 3 and 4, as well as Bacchus et Ariane Suite 2 and the Op.52 Sinfonietta, excellent value indeed. As regards individual symphony performances, the front-runners for me are Bernstein in No.3 and Karajan in No.4. The Third was commissioned by Bernstein’s mentor, Koussevitsky, and the New York recording from 1961 is justly famous. I actually prefer his mellower but no less exciting account from 1981, played by the French National Orchestra and coupled with a superb Franck D minor. Karajan’s pioneering mono account of the Fourth comes from 1949, marvellously played by the Philharmonia at their peak, and coupled with Balakirev’s First Symphony. It is some measure of the musicianship of Munch that this Elatus release can compare with these illustrious accounts in many ways and make one forget the shortcomings. |

|

Return to Index |