This was Pucciniís first opera, his hasty response

to the competition for a one-act opera announced in 1883 by the publisher

Sanzogno. Though he didnít get anywhere Ė the lucky composers were Guglielmo

Zuelli and Luigi Napelli Ė Puccini was already acquiring influential

friends, among them Arrigo Boito, who got up a subscription which enabled

the opera to be produced at the Teatro Dal Verme, Milan, in 1884. It

earned Puccini considerable success and a contract with the publisher

Ricordi. He expanded it into two acts, in which form it reached the

Turin Regio Theatre by the end of 1884 and La Scala the following year.

Further revisions were made in 1888 and 1892, but soon after this it

was overtaken by the masterpieces we all know and fell into oblivion.

It is easy to make fun of this story which opens with

the engagement of two childhood sweethearts in a Black Forest village;

he, Roberto, has just got a big inheritance and has to go off to Magonza

for a few days to get it. She, Anna, has premonitions (of course) that

heíll never come back and he (of course) assures her of his undying

love. So far so good and thatís the first Act (thereís also Guglielmo,

Annaís father, who pops up from time to time without really adding much

to the action). At this point a narrator is brought in to update us

on some bits of story that would not have been easy to show on stage;

Roberto has done the expected and betrayed Anna (of course) for a mermaid

(maybe you didnít guess that bit) who happened to be hanging around

Magonza while he was there and Anna has died (of course) of a broken

heart. There follows a lengthy but attractive orchestral interlude which

enshrines a chorus of women mourners Ė not quite a humming chorus but

something like one. Now the narrator explains that there is a legend

in the Black Forest of the Villi, the spirits of young girls who have

died of broken hearts, who await and avenge the traitor, killing him

in the press of their dance.

So Act 2 opens as Roberto, who has been sent packing

by his mermaid (of course), comes back home full of repentance (of course)

and hoping to find Anna still waiting for him. Anna, now one of the

Villi, does appear to him, but, she explains, she is no longer love

but vengeance. His vain attempt to escape the Villi is blocked by Anna

herself and he is trampled to death in fulfilment of the legend.

It is, as I say, easy to make fun of this. But the

work is an endearing one all the same and it is also easy to see Anna

as a proto-Butterfly figure and the feckless young Roberto as a proto-Pinkerton.

Puccini already showed a marked predilection for lyrical, melodic writing

and he has more orchestral know-how than we might have dared to hope.

He is also definitely a modernist Ė closer to Catalani than to Verdi.

If he cannot breathe life into Guglielmo and if Roberto hardly earns

our sympathy, Anna, particularly on the strength of her Act 1 aria "Se

come voi piccini", can take her place, within limits, among Puccini

heroines.

Lorin Maazelís Puccini cycle for CBS was comprehensive

enough to include Le Villi in 1988. With a cast headed by Scotto and

Domingo and with Tito Gobbi emerging from retirement to play the narrator

(a considerable coup, this), further recordings might seem superfluous.

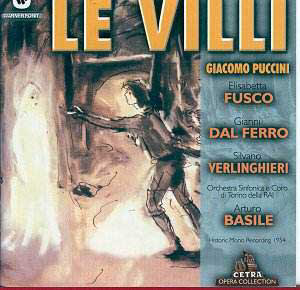

At the time it was made few even remembered its 1954 predecessor; Cetra

LPs were notoriously shrill (I speak in general, I havenít heard the

LPs of this particular recording) and their "Villi", unlike

many, didnít even have a great name in the cast to justify perseverance.

Nonetheless, it proves as modestly endearing as the

work itself. The sound now falls easily on the ear, restricted in the

bigger choral/orchestral moments but clear in the gentler ones and with

the voices producing well. I have already admired Basileís "Chénier"

and "Tosca" in this series; he is a natural Puccinian in the

grand Italian tradition, and he and the orchestra sound as if they have

known this rare score all their lives.

Elisabetta Fusco has a very attractive voice; small,

perhaps, but with real quality over most of its range. This quality

is sometimes carried up over the stave (there are some lovely piano

high As), but on other occasions, usually though not always when putting

more pressure on the tone, she seems uneasy. Obviously there were still

some problems to be sorted out. Even so, I would gladly hear the performance

again for her sincere, convincing portrayal. Dal Ferro is a typically

bright, ringing but not unsubtle Italianate tenor. In an evident attempt

not to be too bright and ringing, he rounds his vowels too consistently

into "o"s, singing "tíomo" instead of "tíamo"

and so on, with the risk that his voice seems at times swallowed back

in his throat. Still, the timbre is attractive. Puccini didnít help

Guglielmo by making him a high baritone rather than a real bass Ė there

is not enough difference between him and Roberto. It also doesnít help

that Verlinghieri, though a decent enough singer, lacks real weight

of utterance. His narration is effective but reminds us that Italian

ideas of elocution have changed as much in 50 years as have English

ones Ė think of the ringing tones of some of the old BBC announcers

in the immediate post-war period or, if you understand Italian, of Mascagniís

spoken introduction to his recording of "Cavalleria Rusticana";

nobody today would narrate it quite like this ("he sounds like

Mussolini" would be the euro-in-the-slot reaction).

Itís a pity that the booklet, while relating the history

of the work (in Italian and in reasonable English; the hilarious title

"The First Pucciniís Opera" cannot be the work of the translator

of the text itself) and giving the libretto (without translation), does

not tell us anything about these singers, though we do get photos of

them and the conductor. It is a matter for reflection that we have here

an opera by a young hopeful who made it, sung by three young hopefuls

who evidently didnít. Elisabetta Fusco has not passed without trace;

she sang Barberina in the famous Schwarzkopf/Giulini "Figaro"

and a small part in the Callas/Schwarzkopf "Turandot". A pirate

issue from La Fenice, Venice, in 1960, has her singing in Handelís "Alcina"

alongside Joan Sutherland. More recently she has been (is?) a voice

professor at Naples Conservatoire. I can find no traces of Gianni Dal

Ferro (who looks, from the photo, to have been rather older) but Silvano

Verlinghieri cropped up, usually in second casts, over the following

decade or so. He sang Escamillo to Simionatoís Carmen in Rome in 1959,

for example, and Amonasro under Serafin in Florence in 1963. The healthy

operatic life of a country (Italy still had a healthy operatic life

in the 1950s) depends on the availability of reliable, honest-to-goodness

practitioners such as these. An issue like this documents this everyday

operatic life, and it would be nice to have more information about those

that made it possible.

I suppose the Maazel (which I havenít heard) will be

the "natural choice" for Le Villi; but this was my introduction

to the music. If itís yours, too, I think youíll enjoy it.

Christopher Howell