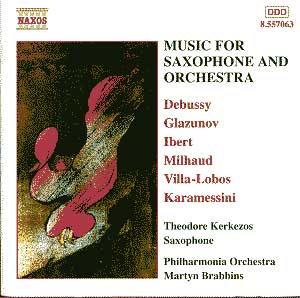

Toulouse-Lautrec’s Loie Fuller graces the cover

of this CD evoking a fin-de-siècle atmosphere most appropriate

for Debussy’s 1908 Rapsodie. Elsewhere we range from Milhaud’s

commedia dell’arte and Ibert’s bustling syncopation through Villa-Lobos’s

nocturnal reflection and Glazunov’s ripe romanticism to Karamessini’s

spanking new ceremonial drama. The saxophone, alto and soprano, takes

on many guises here; prankster and trickster, romantic and saturnine,

crepuscular, balletic, acrobatic, avuncular or Dionysian – there’s plenty

of ground to cover.

Debussy’s Rapsodie was written in 1908 but the

scoring was only undertaken after his death by Roger-Ducasse in 1919.

Its nocturne grows sultry, the saxophone embedded in the score, taking

a primus inter pares role for some of the time – note Debussy’s

explicit title - and flecking it with distinctive cries. Milhaud’s Scaramouche

is better known in its two piano version. Vivacious and vital, its rhythmic

élan is unstoppable; its samba finale with chugging rhythm two

and a half minutes of, as Milhaud writes in the movement heading, Brazileira.

Ibert’s Concertino was written for one of the leading players

of the day, Sigurd Rascher, for whom Glazunov wrote his concerto and

Eric Coates his Saxo-Rhapsody amongst a number of other composers

(Rascher’s superb performance of the Coates is on a Pearl CD). Written

in 1935 and contemporary with the Coates and Milhaud works it is vaguely

Ravelian with a busy, forward moving solo line. There’s a considerable

amount of syncopation and drive and I would agree that the Concertino

was influenced by the – considerable – amount of good Jazz to be found

in Paris in the 1920s and 30s – rather than being in any way explicitly

a jazz work. The Larghetto is pleasant – in the main slow movements

here are elegant without being deep – but the finale much sprightlier.

Its brisk, neo-classical motor threatens fugal overload but bustles

defiantly on to the end.

Villa-Lobos’ Fantasia was written for either

soprano or tenor saxophone though most players take the former option.

It was dedicated to the dean of French saxophonists Marcel Mule (an

album currently devoted to Mule is available entitled ‘Le Patron of

the Saxophone’ – Clarinet Classics CC0013 - and includes the Ibert Concertino

dedicated to Mule’s rival Rascher. Mule disapproved of the high notes

Ibert interpolated at Rascher’s request). Rhythmically diverse with

slight ritardandos to relax into brief moments of romantic expression

the brisk opening movement gives way to a nocturnal second movement

introduced by solo viola. The finale runs the gamut of fleet fingered

virtuosity – from quick runs to high octane trills – in an explosive

passage of spirited enjoyment. After these joyful games the Glazunov

seems as if written in another age - which in a sense it was. It carries

with it the whiff of his Violin Concerto and is lush, romantic, delightfully

scored and unashamed to allow the strings their moment of effulgent

romanticism at 6.50 of this one-movement, nearly fifteen minute work,

the longest of the six. I first heard it on Felix Slovácek’s

Supraphon disc of 1980 and its charm never stales. The occasionally

discursive but animated cadenza is excellently negotiated by Theodore

Kerkezos and that noble fugal ending incisively done as well. Finally

to the Karamessini. Greek born she holds a doctorate in Composition

from the University of Sussex having earlier graduated from Berklee

and has composed widely. Her taut but incident-packed work runs for

fourteen minutes. Inspired by the Dionysian and Apollonian spirits the

saxophone becomes part of the fabric of the argument assuming a "transfigurative"

role. The work has rather a ceremonial, hieratic feel. There is some

splendidly surly orchestral writing in the opening movement notable

for its lines for solo violin and "overblown" saxophone. Colourful

and affirmatory the second movement leads on to a dramatic and sonorous

brass capped conclusion, full of processional vigour.

Excellent performances here from the Philharmonia under

Martyn Brabbins and a soloist of considerable presence – and an enticing

programme as well. This is a well-filled infectious delight.

Jonathan Woolf