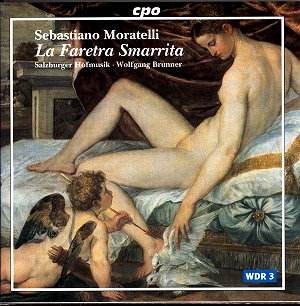

This is a novelty.

Little is known about the Italian musician Sebastiano

Moratelli.

He was born in Vicenza in 1640 and went to Austria

in the late 1650s and was employed in the Court of Arch-duchess Anna

Maria Josepha. On her marriage to the prince elector, Johann Wilhelm,

Moratelli became a member of the Court in Dusseldorf eventually becoming

Music Director. He retired to Heidelberg and died there in 1706. He

wrote operas and serenades (serenatas) often to libretti by Johann Wilhelm's

secretary Giorgio Maria Rapporini. It was thought that all of his music

was lost until the score of La Faretra Smarrita was discovered

in the library of the Counts of Toerring-Jettenbach.

A serenata is a cross between a cantata and

an opera. The plot is trivial.

Mercurio, the messenger of the gods, has lost his golden

quiver with its golden arrows of graces (one is actually called grace

and there are others called majesty, beauty and innocence).

He tells the god Amor who demands to known how this happened. Mercurio

says that he laid the quiver down by a stream in order to 'have sport'

with the beautiful nymphs and it was stolen. Amor and Mercurio travel

throughout the world to try to find this quiver and, as the characters

suggest, they visit Africa and America and then Europe. Here, when Amor

asks about the quiver, there is an echo mentioning the names of Anna

and Arno. Amor comes to the conclusion that a beautiful woman stole

the quiver which has made the thief the personification of love and

therefore worthy of universal praise.

Totally absurd.

This serenata was composed around 1690 and consists

of a brief prelude and 28 short arias and recitatives.

The work is contemporary with fellow Italians, Corelli

and Alessandro Scarlatti and with that great French composer, Rameau.

In England his contemporaries would be John Blow and Purcell. And yet

to my ears his music is so different, Let me quote two main reasons:

namely the absence of fussy ornamentation and the use of a trombone!

While the precursor of the trombone, the sackbut, was known in the sixteenth

century the trombone, as such, was not familiar until the end of the

eighteenth century. Its appearance in this serenata is therefore

strange but somewhat effective.

The music is very polished and, as far as I can judge,

very well performed. There is some excellent singing although I have

to say that the work is not stunning! But there is an airy, out of doors

feel which is welcome. On the other hand this piece is far more attractive

than some secular vocal works by Handel, for example.

I must confess that this work has a strange charm.

I wonder if any more of Moratelli's work will be discovered.

For lovers of early music this is well worth investigating.

The accompanying booklet is a handsome production.

David Wright