Introduction

I will nail my colours to the mast immediately and

admit that I abhor clever, clever modern versions of operas that destroy

the spirit and intent of their original productions. The latest to incur

my wrath is this ARTHAUS production of Korngold’s Die tote Stadt

(The Dead City). Since this work is of great interest to visitors of

both MusicWeb and its sister site Film Music on the Web, I am including

contrasting reviews of both this DVD and the acclaimed 1975 RCA Erich

Leinsdorf world premiere audio recording to demonstrate the difference,

for this reviewer anyway, between the sublime and the ridiculous.

[Granted the original book, on which Die tote Stadt

was based, was colder and more horrific without the life-affirming ending

of Korngold’s opera. This might explain not only the Opéra National

du Rhin’s relentlessly down-beat and more brutal production but also

the concept behind other more recent ‘creative’ productions. One (Götz

Friedrich in Berlin) had Paul interpreted as a possible serial killer

with overtones of sado-masochism and in an American production, Marie

and Marietta respectively resembled Kim Basinger and Marilyn Monroe!

-- More on the Hollywood connection (and Marilyn) follows throughout

this article/review]

Background to the Opera and connections with

Wagner, Bernard Herrmann and Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo

Korngold 1919

Korngold 1919

Die tote Stadt was the most successful of Korngold’s

operas – an amazing achievement for a young man still not twenty when

he began its composition. It was simultaneously premiered in Hamburg

and Cologne on 4th December 1920. The premiere in Hamburg

was a sensation and it became one of the most popular operas in the

Hamburg repertory with well over fifty performances; in fact it was

one of the most frequently performed of all contemporary operas. It

appeared on more than 70 stages in Europe and America. ‘Marietta’s Lute

Song’ and the ‘Pierrotlied’ became smash hits and favourite encores

in their own right.

Die tote Stadt began life as a horror story,

a novella Bruges-la-Morte by the Belgian symbolist writer Georges

Rodenbach – a sort of free variation on the Celtic-derived myth Tristan

und Isolde.

[One might conjecture whether this story influenced

Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac in writing their novel D’Entre

les Morts on which Alfred Hitchcock based his celebrated thriller

Vertigo? The plot line of Vertigo shares many similarities

with that of Die tote Stadt. In fact Bernard Herrmann’s celebrated

score for this film, that has consistently entered the lists of best

film of all time, has been observed to reflect Wagner’s Tristan…

music, specifically the ‘Liebestod’ in Herrmann’s ‘Scène d’Amour’,

in which the hapless Judy Barton (Kim Novak) is made over by Scottie

(James Stewart) to look like his dead love, Madeleine. And Korngold’s

score for Die tote Stadt employs the Wagnerian leitmotif style

and there is more than a passing resemblance to Tristan… More

on this theme later.]

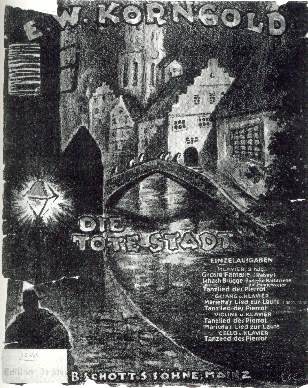

"This cover illustration of the Schott publication

of excerpts from Die tote Stadt, arranged for piano duet, depicts

very well the sort of atmosphere which Korngold sought to portray the

medieval city of Bruges with its dark streets, canals, processing nuns

and tolling church bells."

The story of Die tote Stadt is set in the ancient

Belgian town of Bruges, a dead-seeming city whose bells, still canal

waters, gloomy gothic churches and old decaying houses are for Paul,

the hero, constant reminders of death and impermanence. They are, for

him, the symbol of his saintly dead wife Marie, and the past that he

cannot forget. One room of his house has become a precious shrine to

her memory in which he preserves furniture, photographs and a lute and

above all a portrait of Marie and a braid of her golden hair. Paul lives

alone save for his devoted housekeeper, Brigitta. Then, one day he meets

a woman in the street. Her striking resemblance to his dead wife causes

him to be overcome with strong conflicting emotions. He impulsively

invites her home so that he might see the dead come to life…

Korngold uses a huge orchestra – the largest he ever

used with much exotic percussion, piano, celesta, church organ and a

harmonium for eerie effects, a wind machine, mandolin, sets of bells,

and stage bands as well as a large chorus, separate children’s chorus,

a chamber choir of 16 voices and eight additional female voices off-stage.

The music is approachable and melodic. Indeed in the context of his

operas, Korngold was dubbed the ‘Viennese Puccini’. The leading vocal

parts, Paul and Marie/Marietta, are extremely demanding.

The 1975 RCA CD Leinsdorf/ Munich Radio Chorus

and Orchestra review

From the brief opening opulent, exuberant orchestral

peroration, it is at once apparent that Leinsdorf is conducting large

forces in this 1975 RCA Victor recording. Alas, and this is a major

disappointment and serious omission, the accompanying booklet carries

just the story of the opera and the libretto in German and English.

There are no notes about the history and production of the opera or

about Korngold’s huge score. At that time this was particularly galling

since there was very little Korngold documentation available. Luckily

now, since the Korngold centenary year, 1997, two important new books

on Korngold by Jessica Duchen and Brendan G.Carroll have been published

that include a lot of detail about Die tote Stadt (see footnote

to this article/review for full details about these two publications).

We first meet Brigitta, Paul’s housekeeper (mezzo-soprano

Rose Wagemann) loyal and caring in her lovely, warm-hearted, supportive

aria ‘Was das leben ist weiss ich nicht…’ in which she extols "And

where love is, a woman like me can serve contented…" She is in

the room that is Paul’s temple to Marie with Paul’s friend Frank (baritone

Benjamin Luxon in fine voice recorded without any trace of the excessive

vibrato that spoiled so many of his later performances). Paul bursts

in, in great excitement after seeing Marietta who so resembles his deceased

wife Marie. In his first aria, ‘Nein, nein, sie lebt’, Paul reveals

his obsession with the dead Marie and his belief that she now lives

again in Marietta. At first exultant, then romantically yet morbidly

reflective this aria is a tour-de-force with Korngold’s brilliant

harmonies and eerie atmospheric orchestrations. René Kollo, so

brilliant in the role of Walther in the 1971 Karajan recording of Die

Meistersinger von Nürnberg, here again impresses with his ringing

ardent tones and sensitive musicianship. His Paul is a rounded character

defiant and manly as well as obsessive.

Frank, concerned for his friend’s welfare, offers a

warning and sensible advice in his expansive aria, "…Paul, you

are playing a dangerous game. You are a dreamer. You see ghosts and

phantoms – I see reality, I see women as they are…". But Paul will

not listen and Frank exits. Frank is right: Marietta is quite unlike

Marie. She is worldly and fun-loving. Korngold’s wonderfully rapt music

rises from the orchestra as Paul awaits her arrival in ever mounting

anticipation. But Marietta is annoyed by his apparent distraction -

she cannot comprehend Paul’s introspection and persistent dreaming of

Marie. Carol Neblett’s Marietta is exuberant and carefree as she says

she lives to sing and dance. The orchestral accompaniment switches between

the eerie ghostly world of Paul’s psyche and the lighter atmosphere

of Marietta’s worldly outlook. When Paul shows her the lute that Marie

played she sings the beautiful Lute Song ("Joy, sent from above…")

that was the hit of the opera from the very first. The Kollo and Neblett

duet that is a continuance of that aria is heart-rending indeed and

again the orchestration scintillates.

Marietta demonstrates her flirty nature and goes off

with her theatrical troupe friends with a lingering promise to the distracted

Paul "Those who love me know where to find me. And they can see

me dance at the opera." Act I ends as the opera’s action shifts

from reality to the beginning of Paul’s hallucinatory visions. The ghost

of Marie steps out of the picture (to eerily evocative music) to tell

Paul that he is with her forever, that her braid of hair will guard

him but that "Life comes to claim you, a new love beckons…".

The apparition disappears and is replaced by another of Marietta in

a hedonistic dance. Paul is ecstatic

.  "

"

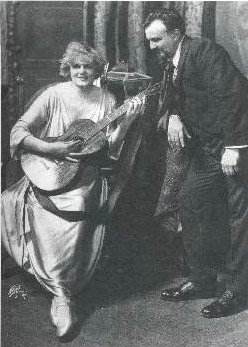

Maria Jeritza as Marietta and Orville Harrold as Paul

pictured during the dress rehearsal of the 1921 New York Metropolitan

Opera production of Die tote Stadt. Jeritza carries a guitar

that stood in for a lute (Metropolitan Opera Archives)."

Act II is a continuation of Paul’s fevered dreaming.

He wonders disconsolately by a canal close to Marietta’s house. In an

extended orchestral interlude with brilliant orchestral effects (organ

and wind machine included): huge bells toll and an oppressive gothic

atmosphere hangs over all. The Bavarian players here, as they are throughout,

are superb and the sound engineering stunning. Paul in another extended

aria berates himself for prowling about after Marietta and "tasting

bitter pleasures". He recalls purer, more innocent times. Brigitta,

passing by, admonishes Paul for desecrating the memory of Marie and

goes off to church. Frank appears and berates Paul too saying, "You

are not right for her, you’re sharing death and life with her. She wants

complete fulfilment. We are Harlequins who adore her and she is Columbine

who seduces us and enslaves us." Paul’s jealousy is aroused when

he realises that Frank has succumbed to Marietta’s charms too and declares

that Frank is no longer his friend.

Marietta then approaches with her friends. They are

in boats on the canal. They flirt and sing waltz songs. One admirer

who Marietta has cast aside, Fritz, Marietta’s ‘Pierrot’, sings the

other big hit number from the opera, "Mein Sehen, mein Wähnen…"

(My dreaming, my yearning) in which he remembers young love and dancing

"by the Rhine in moon’s golden shine". Baritone, Hermann Prey,

I fear, is too solemn, too intense for this loveliest of waltz songs.

Marietta then suggests they rehearse Hélène’s

scene from Robert le Diable in the streets. The sounds of an

organ from a nearby cathedral, processing Beguine nuns and dark clouds

form an ominous background for this heavily ironic scene as Marietta,

acting as Hélène, rises from a coffin and dances seductively

towards one of her admirers. This is another powerful set piece with

horrifically evocative music from Korngold’s huge orchestra. Scandalised

and outraged, Paul rushes from out of the shadows to curse Marietta

and her friends. "You, a resurrected woman? Never?" Abashed

and embarrassed, Marietta’s friends depart but Paul continues to hurl

accusations at her and in doing so he reveals his suppressed emotions.

Marietta is deeply hurt but decides to take up the struggle against

her dead rival. She musters all her powers of persuasion and overcomes

his protestations. But when he suggests they go to her house she replies

"No, to yours, to her house". There she wishes to banish the

ghost of Marie forever… The act concludes with another dramatic love

duet.

Another ravishingly orchestrated Prelude opens Act

III that continues Paul’s hallucinations. Marietta has spent the night

with Paul in his house. In the early morning she enters Paul’s shrine

and confronts Marie’s portrait. In a bitter aria she rounds angrily

on the dead wife - "You, who are dead and buried; rest in peace

and slumber. Don’t haunt the living … leave us to revel in joy and pleasure

…" Marietta hears in the distance the purity of a children’s choir

and rejoices in their supplication a brief glimpse at another side of

Marietta’s complex personality.

Paul enters, suspicious of her presence in his ‘temple

to Marie’ and immediately puts Marietta on the defensive. She is even

more determined to dispel the ghost of Marie once and for all. Outside,

the enlarging religious procession draws closer. Paul is alarmed that

they will be seen together and pushes Marietta away from the window.

This makes her taunt him even more in a coquettish aria full of spite

in which she yearns for her carefree past with her admirers. She blasphemes

the procession outside – "You keep them, your pious masqueraders!"

The procession is right outside now and there is a tumultuous choral

and orchestral climax with Paul commenting wondrously on the holy statues

and banners. Marietta acquiesces to his mood and begs him to kiss her.

Paul shocked draws back. "Not here, not now". "Yes here,

now", she demands. Their subsequent quarrel becomes ever more heated

(both chewing the scenery over vicious orchestral chords) and in the

end Paul strangles Marietta with Marie’s braid of hair.

The stage darkens. Paul awakens from his dream. Brigitta

enters to say that the real life Marietta has returned. She finds Paul

silent and stunned by his dream. Thinking he is uninterested – she shrugs

and goes away. Frank enters, notices Marietta’s departure and sees that

the young dancer no longer fascinates Paul. This is the miracle he had

wished for his friend. Paul agrees that he will never see Marietta again

and that his nightmare had destroyed his dream of love, "The dead

send dreams like that to haunt us if we don’t let them find peace in

their slumber," he observes. Frank plans to leave Bruges and Paul

agrees to go with him to find a new happier life. Paul’s final aria

in which he pays a final farewell to Marie "Wait for me in heaven’s

plain…" is sung to the same glorious tune as Marietta’s Lute Song

of Act I.

"A scene from the original 1920 Hamburg production

of Die tote Stadt. From left to right: Walter Diehl (Graf Albert);

Josef Degler (Fritz) Anny Münchow (Marietta); Felix Rodemund (Gaston);

and Paul Schwartz (Victorin)."

The depth of this review is intended so that a more

effective comparison can be made between this conventional production

that Korngold would have envisioned and that of the Opéra National

du Rhin as presented on the ARTHAUS DVD ---

The 2001 DVD Video Opéra National du Rhin

production review

First of all it should be recalled that Korngold is

best remembered for his Warner Bros. film scores written in the 1930s

and 40s principally for Bette Davis and Errol Flynn. This Opéra

National du Rhin production team - Charles Edwards (set design and lighting)

and Magali Gerberon (Costumes) - has clearly borne Korngold’s Hollywood/film

connection in mind. And the close similarity between the stories of

Die tote Stadt and Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo has not

escaped them either. These influences pervade this production which

frankly repels (although some aspects of it have a perverse fascination,

especially in the second act). In many respects it goes against the

spirit of the original production that Korngold knew and as described

in the 1975 premiere CD recording reviewed above.

The Act I set showing Paul’s shrine to the memory of

Marie is seedy and run-down. Part of the set looks as though a bomb

has hit it. The treasured portrait of Marie leans against a wall rather

than hanging in pride of place. Paul’s housekeeper Brigitta (Brigitta

Svenden) is blonde, bespectacled and buttoned up in a high-collared

oriental-style suit. She looks something between Midge (Barbara Bel

Geddes), Scottie’s erstwhile girlfriend in Vertigo and Beatrice

Lilly as the cantankerous, kidnapping landlady, Mrs Meers, in Thoroughly

Modern Milly. Svenden, in her big aria in which she assures Frank

she is happy in a house with an atmosphere of love (even dead love)

is appealing but she is a little unsteady and in danger of being swamped

by Korngold’s effulgent orchestrations.

A little later she is required to bring roses into

the temple. She brings not live flowers but rose-decorated wallpaper.

There is worse madness to come, folks.]

Frank (Yuri Batukov) is sturdy and comforting.

Paul, a heavy-jowled Torsten Kerl, wears trousers at

half mast and has long blonde tresses that make him look like some demented

Little Lord Fauntleroy. As Marietta arrives he is seen clutching a doll-effigy

of Marie. He appears in front of Marietta looking like some miserable,

self-pitying girl’s blouse -- no wonder she is non-plussed! At one point

he even makes a quivering Stan Laurel look heroic. By the time he commits

suicide at the end of the opera (yes, suicide, more about this clanger

later), one has lost all patience and sympathy for him. Kerl’s voice

is powerful enough to project above Korngold’s heaviest music but it

lacks Kollo’s attractive timbre and his expressive subtlety.

Marietta has long wide curly blonde tresses and wears

a decorated white Columbine-like dress and inelegant black footwear

calculated to rile the fashion police. Angela Denoke’s acting is very

persuasive and her bright voice projects strongly. Pity she is let down

by the stage directions. One’s jaw drops in utter horror and disbelief

at what happens next. Marie’s lute that Paul shows her is cast aside

in favour of a piano accompaniment (played by some inexplicable character

unconnected with the opera who just strolls on to the stage) as she

sings Marietta’s Lute Song. As she sings Paul writhes on the floor,

and, horror of horrors, pulls out of from a trapdoor beneath him a skeleton

arm (belonging, one guesses to Marie) and proceeds to kiss it. Clearly

the effect of this lovely aria is totally crushed but so too is Marietta’s

joyful song a little later. Here she stands over a storm grating (in

the middle of a room?) while upward air currents billow out her skirts

like those of Marilyn Monroe in The Seven Year Itch (but Monroe

played an innocent concerned only with keeping cool in a New York heat

wave). Back to Vertigo: Saul Bass’s unsettling kaleidoscopic

spiral patterns that were used for the film’s opening titles are seen

here in a huge circle projected high to the right of the stage. This

pattern blends into a close up of part of Marie’s face as her apparition

informs Paul that a new love awaits him, as Act I ends.

Act II sets are equally bizarre, but fascinating, in

keeping with Paul’s nightmare visions. The circle with Marie’s face

fades and ghostly images of Bruges take their place with figures in

medieval dress moving about the stage through the Prelude. Then a huge

bell descends and a depressed Paul tries to hang himself from its rope

but is dissuaded by passers-by. The bell lowers to the ground and turns

over so that the audience is looking deep inside its dark circle. From

inside, the image of Brigitta appears to disparage Paul. Then Frank

appears on stage with a bushy red tail, red hair and horns – now clearly

a devilish apparition. When Paul discerns that he has designs on Marietta

too he kills Frank in a radical departure from the original opera story

line. The Harlequinade that follows seems as though it is set in Las

Vegas with neon lights and brassy bars. Marietta’s friends in garish

costumes look as though they are fugitives from some Fellini film. Nuns

tear off their habits and are seen in skirts resembling the Stars and

Stripes. On the credit side, however, Fritz’s (Pierrot’s) aria sung

by a lighter voiced Stephan Genz is spellbinding and much more moving

than Hermann Prey is on the Leinsdorf CD.

Act III brings yet more visual horrors. The religious

procession, in garish costumes and ghoulish make-up, seems to emanate

from beneath the earth. Paul demonstrates his religious fervour and

guilt by clinging, in a posture just short of blasphemy, to a large

cross. This cross is tugged between an incensed Marietta and himself

who taunts him so much that he kills her not with Marie’s braid of hair

but a knife.

In this outrageous production one wonders if Paul ever

awakes from his nightmare. Frank as a ghostly apparition appears still

in his scarlet tail and horns to give him the knife which Paul uses

on himself as he sings that final aria then falls in his death throes

and blooded against a door marked NO EXIT. This ending of course runs

totally contrary to the original opera’s life-affirming ending and purpose

of Paul’s visions. It is all very sad because there is some fine singing

and Jan Latham-Koenig, although not in the same class as Leinsdorf,

delivers fine dramatic and atmospheric music from what I perceived to

be rather smaller forces than in the RCA recording.

Conclusions

First this bizarre production prompts one to wonder

how Korngold would have scored Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo had

he survived into the 1950s and presuming, of course, that the master

of suspense would have hired him. Not wishing to disparage Bernard Herrmann’s

excellent score in any way, my guess is that the story would have fascinated

Korngold and that he would not have been able to resist it. I think

he would have brought a deeper insight into the predicaments of the

characters of Scottie and Madeline/Judy Barton.

But to a final assessment of the two recordings.

The RCA premiere recording released in 1975 is unhesitatingly

recommended. The lead roles (René Kollo and Carol Neblett) are

sung with passion and conviction and the expanded Munich Radio Orchestra,

recorded in spectacular sound, sounds magnificently opulent.

The new Arthaus DVD is, in comparison, weighed down

with ridiculous, garish sets, costumes and effects (although there is

no denying that sometimes they have a powerful fascination). Angela

Denoke shines as Marietta/Marie despite everything that happens around

her, and there is a memorable cameo from Stephan Benz as Fritz the Pierrot

in one of the opera’s great hit numbers. But Torsten Kerl cannot match

René Kollo in voice and his gross over-acting disappoints.

If you must watch the DVD just hire it from a library

and buy the Leinsdorf recording to treasure.

Ian Lace

Footnote

Further details about Die tote Stadt and the life and music of

Erich Wolfgang Korngold may be found in the following two books:

The Last Prodigy – A biography

of Erich Wolfgang Korngold

By Brendan G. Carroll

Published by Amadeus Press ISBN I–57467–029–8

Erich Wolfgang Korngold

By Jessica Duchen

Published in Phaidon Press’s 20th Century Composers series

ISBN 0-7148-3155-7