Both concertos date from around 1830, and how amazingly

unlike Beethovenís Emperor they are. Piano writing was advancing

in leaps and bounds, diversifying in all directions as the instrument

itself developed in terms of its technology. Chopinís two concertos,

together with the Andante Spianato and Grande Polonaise, have

a reputation for shallow sparkle and turgid orchestration but both descriptions

are wholly inappropriate, especially when they are in the hands of sensitive,

informed performers. They have an endless stream of inventive melody,

lyric emotion and lithe energy, while such devices as col legno

(using the wooden part of the bow to strike the violinsí strings rather

than the hair to draw the sound) must represent, along with Berlioz

in his Symphonie fantastique from exactly this same period of

1830, an early departure from the conventional approach. Then thereís

the Polish dance (the Krakowiak in the finale of the first concerto)

to catch the spirit and rhythm of Chopinís homeland, which he left for

good at this time.

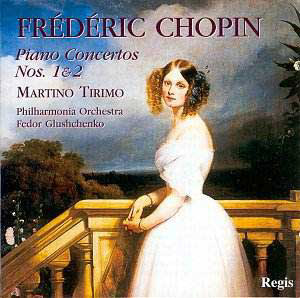

This is a very fine recording. Tirimo, who already

comes with an excellent reputation in Schubert playing, brings his translucent

technique to these vivid accounts. What particularly strikes one is

the partnership between soloist and orchestra in what are frankly purely

vehicles for a virtuoso to strut his or her stuff while the orchestra

takes on the role of an also-ran. Not so here. The Philharmonia are

in glowing form under Glushchenko, fabulous horn and bassoon solos,

warm string tone and immaculate accompaniment while Tirimo meanders

through the filigree forests of embellishment so typical of Chopinís

piano writing. Quite the finest playing since Vlado Perlemuter, whose

recently announced death at 98 robs us of one of the great Chopin exponents,

and definitely one for the shelves.

Christopher Fifield