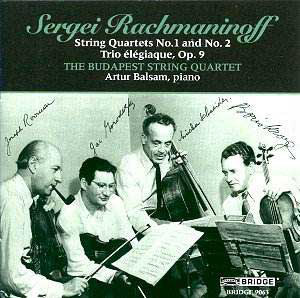

In their recital at the Coolidge Auditorium of The

Library of Congress on 4th April 1952 the Budapest Quartet

and Artur Balsam programmed an all Rachmaninoff programme. The Quartet

disinterred the two incomplete apprentice quartets – both in two movements

only, in the edition by Dobrokhotov and Kirkor – and added the Op 9

Trio with Balsam. All these are early works, the Quartets dating from

1889 and 1896 and the Trio from 1893, though it was substantially revised

in 1907 and again during 1917.

The 1952 line-up of the Quartet was Joseph Roisman,

Jac Gorodetzky, Boris Kroyt and Mischa Schneider. Gorodetzky, though

Russian like the others, came from a different musical background inasmuch

as he was from the Franco-Belgian school and had been the second violin

of the Guilet Quartet, distinguished exponents of the repertoire and

one of France’s best pre-War Quartets. As Alexander Schneider always

maintained, despite their Russian birth the Budapest considered themselves

essentially Germanically trained and so the French orientated Gorodetzky,

who replaced Edgar Ortenberg, contributed an admixture of lightness

and flexibility to the quartet’s texture.

The then seldom-performed Quartets (much less so even

than now) emerge well from these performances. The First opens replete

with more than a whiff of the Budapest’s occasional perfumed style and

Boris Kroyt, whose viola has a substantial and prominent place in the

ensemble, begins a little hoarsely, though this is exacerbated by the

rather clinical acoustic of the Coolidge Auditorium. The second movement,

a Scherzo, opens in boldly confident style, with a second subject pizzicato-led

and of moderate gravity, well-played and wittily done. All the works

on the disc owe a huge and unignorable debt to Tchaikovsky and this

one more than most. The Second Quartet shows a somewhat greater weight

of melodic inspiration, its slow second movement being especially intriguing.

It has a sepulchral Passacaglia like form which gains inexorably in

emotive power throughout its ten minute length and the eventual return

to the saturnine opening is well-judged by the players with just the

right weight of withdrawn tone.

The Trio features Joseph Roisman, Mischa Schneider

and Artur Balsam. I like the rise and fall of Balsam’s strong chording

in the first movement and even the rather slithery string playing at

5.00 – it’s excitingly done. Balsam plays the passage from 7.02 onwards

with true singing tone with underpinning by the strings and the playing

generally is marked by metrical flexibility. Roisman and Scheider exchange

phrases at 17.00 onwards with masterly understanding and tonal blend.

In the Quasi variazioni second movement, which are based on The Rock,

a flowing tempo is accompanied by an expressive profile – this is Rachmaninoff’s

tribute to Tchaikovsky who had been so impressed by The Rock that he

offered to conduct the first performance and in the avowed tradition

of Tchaikovsky’s own elegiac trio, itself dedicated to Nikolai Rubinstein.

In the finale Balsam is incendiary – even banging at 4.20, a feature

doubtless magnified by the dry recording – but his dynamics are good

and the string players though not always watertight of ensemble make

a fine showing especially in the explicitly Tchaikovskian draining away

ending to the work.

The lack of bloom of the Coolidge Auditorium is a simple

fact of acoustic life - admires of the Quartet won’t hesitate to acquire

these performances despite the unflattering nature of the sound – because

discographically these are tremendously interesting additions to the

Budapest’s corpus of surviving works. Notes are by the perceptive if

here slightly non-committal Harris Goldsmith.

Jonathan Woolf