Arturs Maskats studied at the Latvian Academy of Music,

graduating in 1982 when he was twenty-five. He spent the following sixteen

years as music director of the Daile theatre, composing music for over

ninety theatrical productions throughout his native country. He is now

artistic director of the Latvian National Opera and harbours two dreams

– to write a series of symphonies ("Symphonies are an impractical

genre but one should write at least four") and to investigate the

tango. I welcome the former heartily but hope he can be dissuaded from

the latter – the world is already suffering a pandemic of Piazzolla

inspired tangos.

If Vasks is Latvia’s most internationally known composer

Maskats is clearly imbued with something of the same inwardness of feeling

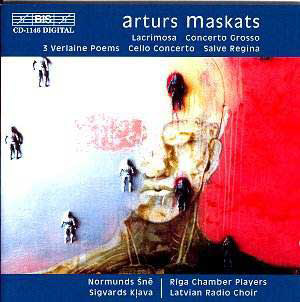

and the technical means by which to convey it. On this BIS disc, intelligent

programming and production as ever from this company, choral works begin

and close with a centerpiece vocal ensemble work around which sit two

big orchestral pieces. Lacrimosa was premiered on the first anniversary

of the sinking of the ferry Estonia, with eight hundred lives

lost. Opening with the choir almost inaudible it gains in amplitude

throughout its seven-minute length, ostinato violins and an increasingly

strident and interjectory organ adding their own discerning moments.

This leads to a clash of tonalities in the choir, produced by the increasingly

fractious and turbulent writing, before a reconciled peace slowly develops

– a memorial piece of depth and one that abjures simplicities. The five

movement, classically based Concerto grosso of 1996 opens with the obscure

plink of the percussion and then with Pärt like stasis but soon

violin, percussion and then cello become heated before a return to the

initial percussion notes and a musing violin. Lest this should conjure

up images of Holy Minimalism the composer I’m most reminded of in the

strong second movement allegro is none other than Brahms. There is a

strongly string based affinity with the Double Concerto in this Concerto

grosso and one that co-exists with moments of neo-classicism. A spectral

percussion (vibraharp?) haunts the slow movement over ominous pizzicati

– some beautiful string writing and playing here - whilst the fourth

movement allegro is one of the most convincing of all. There is a strong

sense of romantic dialogue here and a growing ferment over increasingly

acerbic orchestral background support – in the foreground the cello

holds onto a slithery harmony and the percussion whip cracks the movement

onwards. The cadenza here is an energetic and taxing late romantic,

Brahmsian affair. The last movement – an adagio – returns cyclically

to the material of the opening one, ending the piece with a musing somewhat

enigmatic profile. Don’t expect Tippett’s Corelli Variations. This is

a work that takes the bones of classical structure and clothes them

with a greater weight of romantic sensibility than is perhaps wise but

as Maskats himself says "do not be afraid of these things."

The Cello Concerto was premiered in France in 1992,

the year of its composition, and was inspired by the daughter of the

Latvian composer Jekabs Medinš. It’s elegiac in feeling, lasting seventeen

minutes, the five movements running seamlessly together. Maskats has

used elements or motifs from two of Medinš’s own cello concertos and

woven them into the syntax of his own work which is meditative without

being portentous. Whilst not initially compelling in thematic material

it has a kind of lateral depth that works on its own terms. The Verlaine

songs for choir, oboe and cello are well-crafted affairs. The first

has curling and yearning cello and oboe; the choir wittily intones Debout,

paresseux! (Get up, lazy ones) in the second whilst the third is

crepuscular with oboe and cello now coiled around each other. The disc

is completed by the Salve Regina, a predominately penitential setting,

with Antra Bigaca the eloquent mezzo.

Maskats is another strong voice in the Latvian musical

landscape. An avowed admirer of Vasks he is clearly also an absorber

of late Romanticism. Whilst he never puts it to as vividly creative

a use as, say, Arne Nordheim, this lends Maskats an immediacy that is

frequently affecting. Sound and documentation are all one has now come

to expect from BIS. Recommended.

Jonathan Woolf