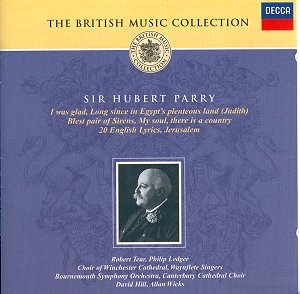

Well, I see the problem. Decca are ploughing their

back catalogue, often very ingeniously, to set up a "British Music

Collection" and today Parry and Stanford are, if not exactly standard

repertoire, no longer written off as Victorian/Edwardian gentlemen with

no relevance to the real world. They clearly had a place in the series

and the trouble is that Decca’s back catalogue is not exactly rich where

these composers are concerned. (Nor is that of any other major company,

though EMI did at least chalk up a symphony by each composer in the

LP era).

Basically this compilation derives from two discs.

One, made quite recently (1990), consisted of English Anthems with orchestral

accompaniments (the other composers were Stanford, Elgar, Hadley and

Bairstow) and was issued on the resuscitated Argo label. The other goes

back to 1977 (the CD booklet says "London 1979", I took the

information above from the LP sleeve, which I presume to be correct)

and also appeared on the Argo label. All twenty songs from that LP are

transferred here to form the centrepiece of a recital which places in

stark contrast the public and the private sides of Parry. The presence

of a Canterbury version of "My soul, there is a country",

not unwelcome in itself, causes one to wonder if Decca have forgotten

that the Argo catalogue also contained another of the few major Parry

recordings of the pre-CD era: the complete recording of the "Songs

of Farewell" by the Louis Halsey Singers, issued in 1978 (ZK 58)

and also containing some Stanford part-songs which have not been subsequently

available in these or other versions.

I confess I have always had a problem with "Blest

Pair" and "I was glad". The music has always seemed,

on paper, to have an electricity which doesn’t come across in performance

(didn’t someone describe Parry as a "fiery whirlwind of genius"?).

In "Blest Pair" there could be a reason for this. The marking

in the vocal score is "Allegro moderato, ma energico". But

in fact the "ma energico" part of the instructions (presumably

authentic) is not reproduced in the full score, which says only

"Allegro moderato", so many who conduct the work may have

seen only that. Way back at the time Boult’s EMI performance came out

I remember being distressed at finding it a very moderate allegro without

a trace of energy in sight. Yet that is how the work is always interpreted

– David Hill follows the tradition – and Boult’s memories went back

a long way, long enough to have known how it was performed at a very

early stage in its life. Yet I remain unconvinced. I have tried to appreciate

the dignity of the Boult way, and I must say that in this performance

Hill does make some response to the "Animandosi" and "Più

moto" directions (leading up to letter C), more perhaps (but I

speak from memory) than Boult himself, but I find the whole thing spineless

and soggy. Does not the undeniable resemblance of the opening to Wagner’s

"Die Meistersinger" overture offer a clue as to how it is

to be performed? Even the slowest interpretations of that piece have

more shot in the arm than this.

My feelings about "I was glad" are much the

same. I know it was written for a coronation and had to be terribly

dignified, but it was a king that was being crowned, not a dinosaur,

and while dinosaurs collapse under their own weight, there’s no reason

why kings should. I’m not proposing to jazz it up, just to move it forward

a little more purposefully and maybe let some light in on the mushy

textures if it could be done.

Still, good traditional performances if that’s how

you like the music to sound.

Many who have noted that Parry’s gorgeous and well-loved

hymn tune to "Dear Lord and Father of mankind" comes from

an oratorio called Judith must have wondered what the whole oratorio

is like. Alas, those who took the trouble actually to dust down the

score found that it is not by any means one of the Parry works that

cry out for revival. While the words of Whittier’s hymn are quite as

beautiful as the music (it was an inspiration on somebody’s part to

bring them together) the words in the oratorio are nothing in particular,

and the third verse is set to a variation on the theme that lacks the

sublime inspiration of the original. If it had been sung here by a great

contralto/mezzo in the Ferrier/Baker mould – as Parry surely intended

– all would have been worthwhile. Sung plainly and blandly by a boy

chorister it makes no impression - equal to that of singing it yourself

in church.

As I said above, the Canterbury "My soul, there

is a country" is not unwelcome, indeed it is finely sung and interpreted.

However, this is not really church music (not that there’s any harm

in using it as an anthem) and Halsey’s mixed choir shaves some of the

Anglican atmosphere from it. He also builds up more tension in the final

stages and his adult singers have bigger lungs to encompass the long

lines of "One who never changes". Further, recourse to the

Halsey record need not have restricted choice to this piece (it is the

first of a cycle of six) and I would certainly have traded the Judith

excerpt for "Never weather-beaten sail" or "There is

an old belief".

I was partly disappointed in the Tear LP when it appeared

and have not heard it for many years. Rehearing it, my old reservations

remain, but seem rather less acute. For one thing, Tear had an attractive,

evenly and easily produced voice right through his range and crystal

clear diction, and somehow these are things we took more for granted

in those days. And it does get off to a good start. I found and find

"Bright Star" lacking in repose, particularly from the pianist,

but I can fit in with this view more easily now. With "When comes

my Gwen", alas, certain things are all too much as I remember them.

The piano introduction seems to want to inflate it into a "Blest

pair of Sirens" style. I can’t call this Allegro. Then the left

hand octaves are decidedly staccato when they are supposed to be legato

– hence the lumpy effect. And Ledger adds an F to the top of his last

chord of the introduction, changing the melodic line (and repeats this

later). Why? The song goes better after Tear has entered though I still

question the basic tempo, which replaces Parry’s excitement with something

closer to a serenade.

"O mistress mine" is a little heavy-handed

from the pianist and hardly competes with the classic Baker/Moore version,

but "Blow, blow" is finely done, as are other Shakespeare

and Elizabethan songs later in the programme, "When icicles hang

by the wall", "Take, O take those lips away", "No

longer mourn for me" (but this is a curiously unsuitable and undistinguished

setting) and "And yet I love her till I die". A very famous

song of this type – a Ferrier speciality this time – is "Love is

a bable". It is excellently done except for one point. Where is

Parry’s "dolce" at "Love is a wonder"? Is this not

the point where the thing goes serious for a moment?

The "Welsh Lullaby" is very beautiful indeed.

I get the impression that the piano has been unduly close-miked (to

minimise the effects of a church acoustic?) and some of the impressions

of heavy-handedness on the part of the pianist may be due to that rather

than his actual playing.

"When lovers meet" is well done from both.

Tear was one of the first serious singers to revive Victorian/Edwardian

ballads and he tends to be most at home with the songs which approximate

to that style, maybe overdoing the portamentos and certain other tricks

of the ballad-singer’s trade, but presenting a view which is valid from

its own point of view. Other songs in this category are "When we

two parted", "Thine eyes still shine for me" (well, this

one perhaps is nothing more than a popular ballad, frankly) and, as

interpreted here, "There be none of beauty’s daughters", of

which a more amply phrased interpretation can be imagined.

I should say at this point that, when the record came

out, my ears were very full of a selection of the songs, several repeated

here, that I had taped off Radio 3 sung by Wendy Eathorne (soprano)

and John Barrow (baritone). I felt they both presented their songs with

more genuine feeling. I haven’t looked out that tape, since few if any

readers will have access to these performances, but I do remember that

Wendy Eathorne took a wide range of tempi in "On a time",

interpreting it very freely and, it seemed to me, magically. Be that

as it may, I now have to admit that the light-hearted, tripping interpretation

Tear and Ledger give us does seem to be what Parry wrote. In the same

vein, they give "Marian" a delightful lilt.

"Weep you no more" – a gorgeous setting –

is one that I appreciated more for having distanced myself from other

interpretations. Mellifluous and satisfying as sheer singing and playing.

"Looking backwards" is more of a problem. For Tear and Ledger

this would seem another of the Victorian/Edward ballad-type songs. Memory

insists that John Barrow demonstrated that a good deal more genuine

emotion is to be extracted from this, one of Parry’s most heartfelt

utterances. Indeed, when the melodic line becomes broken at such moments

as "And heaven is bare, for God is far away. Canst thou not come

and touch my hand again", an interpretation which depends on vocal

elegance, lacking in the sense of sheer desperation which words and

music imply, has little sense. This song is one of the very few compositions

Parry dedicated to his wife. Written in 1907, it uses a text by Parry’s

friend Julian Sturgis which remembers a long lost child love and surely

offers a bitter commentary upon a relationship which had long fallen

into the rut of bare tolerance. For details of Parry’s marital relationship

(and for a generally penetrating study of the composer), readers are

referred to Jeremy Dibble’s "C. Hubert H. Parry: His Life and Music"

(Oxford 1992).

"From a City Window" is another of Parry’s

very greatest creations, and finds Tear and Ledger uncertain what to

do with it, exaggerating the difference between the tempi of the outer

and middle sections and finding more elegance than emotion in the heartfelt

central cry. And how extraordinary that Tear’s cutting of a whole beat

at "A bird troubles the night" was not thought worth a retake.

The final song, "There", is another whose mystic and profound

qualities are resolved with vocal elegance and clear diction. By and

large, one gets the feeling that, while Tear no doubt realised that

these songs were more important than the ballads on his best-selling

"Owl and the Dicky-Bird" album, he was reluctant to recognise

how great Parry could be. Where charm and elegance is enough, he produced

interpretations that will not be easily surpassed, but the full range

of Parry’s writing is short-changed. The disc was made at a time when

Parry was still almost universally derided, and perhaps reflects this.

The original LP was criticised for not supplying the

texts; things haven’t changed. This reissue does not even name the poets

of the songs, which would have enabled those with a reasonable poetry

bookshelf to assemble about three-quarters of them. The clarity of Tear’s

diction helps, but I won’t let up on this one. Records of songs need

the texts.

The programme ends with "Jerusalem", a piece

you can hardly go wrong with.

If this is intended to introduce new listeners to Parry

in the round, then I feel it will give a lopsided impression; it could

perhaps have been entitled "Songs, Anthems and Motets". The

fact that two out of four works with orchestra have orchestrations by

other hands will not dispel the old legend that Parry couldn’t write

for orchestra, especially when the orchestration of the other two is

pretty drab (but these are early works; Parry later learnt to do much

better). A note by Raymond McGill seems to have been written about twenty

years ago, blandly justifying the choice of repertoire with the comment

that "there are few opportunities to hear any of his orchestral

works". And none at all relying on the Decca back-catalogue. That’s

the problem, as I stated at the outset. Still, admirers of British song

will be glad to have the Tear recordings back in circulation.

Postscript: curiosity did lead me to look out the taped

broadcast I referred to above. 8 songs were recorded by Wendy Eathorne

with Geoffrey Pratley and broadcast on 3rd July 1976, and

a further 8 by John Barrow with Wilfred Parry followed on 7th

August of the same year. My memory was not at fault. In "On a time"

Wendy Eathorne opens up a whole range of interpretation which Tear’s

simple run-through does not attempt, and reveals a far finer song. The

gains are marginal in Barrow’s "Weep you no more" but "Looking

backward" and "From a city window" have a passionately

lived-in quality which shows these songs as the visionary creations

they are. One wonders what happened to these singers. I remember the

name of Wendy Eathorne cropped up from time to time in the 1970s but

I never heard John Barrow mentioned in any other context. I reheard

both with pleasure, particularly Eathorne, the best kind of British

light soprano, clear and true in timbre and a genuine interpreter of

what she sang.

Christopher Howell

see also review by Jonathan

Woolf