Cycles of Messiaen’s organ works aren’t quite as much

like buses as this double review would imply. True, we’ve been waiting

ages for another one, especially one from Olivier Latry, but of the

two that have turned up at once we’ve had the chance to get to know

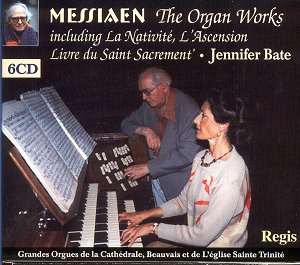

one already, for the Regis box is a repackaging of Bate’s pioneering

cycle for Unicorn-Kanchana. All the same, only those who already have

Bate’s complete cycle on CD can pass over this re-release, for it is

offered at the price of two Unicorn-Kanchana discs (say, containing

Livre du Saint Sacrement) and includes both Messiaen’s and Felix

Aprahamian’s well-worn notes. Those who are familiar with the music

are likely to be familiar with these too, so ubiquitous were they at

one stage for lack of competition, but Aprahamian’s plain-spoken erudition

and Messiaen’s curious prose, which manages to be at the same time brusquely

descriptive and evocatively colourful, are certainly worth re-reading.

While Paul Griffiths’s notes for the DG box are new, their lamentable

brevity means any one movement is lucky to get a sentence to itself.

As for so much else about the man and his music, Faber’s ‘Messiaen Companion’,

edited by Peter Hill, is simply invaluable for going behind the notes

and while some of Gillian Weir’s judgements on the aesthetic quality

of individual works are at least questionable (Livre d’Orgue

comes in for a bit of a pasting) her immense practical experience of

the works and insightful, musicianly writing ensures that you come away

much the wiser about what remains an extraordinarily varied corpus.

I’ll pre-empt anyone looking for a quick either-or

recommendation: both sets are outstandingly well played. Both also deal

with Messiaen’s different musical languages, periods and styles with

sensitivity and imagination. If you think a string quartet has to travel

a long way from the darting brilliance of Beethoven’s op.18 set to the

otherworldly sound and fury of op.135, how much further Bate and Latry

have to extend their sympathies and technique here. Messiaen’s earliest

published work, Le Banquet Céleste (1932), is a classic

of simple mysticism, slow-moving chords with the radiance shining from

added sixths and sharp-saturated key signatures; Livre d’Orgue

(1951) charts territory that sounds defiantly modernist even today with

its concluding Soixante-Quatre Durées, an infamous masterpiece

of rhythmic serialism; the apparently compendious nature of Livre

du Saint Sacrement (1984) hides what can still be identified as

a distinctive ‘late’ Messiaen style. The analogy also holds good for

the tripartite bundling of the cycles – op.95 and the Verset pour

la Fête de la Dédicace (1960) blur the boundaries slightly,

but the merits of and differences between Bate’s and Latry’s approaches

to the cycle are most evident when considering it in three chunks.

As the cycle most often played by organists who don’t

venture further into Messiaen’s music, La Nativité du Seigneur

(1935) receives performances that in both cases reveal the difference

between knowing a piece of music and knowing the composer who wrote

it (Simon Preston’s Argo recording used to be touted as definitive but

the passage of time now makes it seem little more than flashy). Bate

chooses consistently faster tempos that reveal the kinship between Messiaen’s

early style and other, more conservative giants of French organ writing;

Widor, Tournemire, Dupré. In this her approach is more similar

to other organists than Latry’s, whose interpretation consistently stresses

that although Messiaen’s music emerges from this world, its composer

was already possessed of a quite different pair of ears. The Indian

rhythms of the cycle’s still centre, La Verbe, meander more meditatively,

though no less precisely, in Latry’s hands. Dieu parmi nous closes

the cycle with an epic grandeur that to some ears will sound a mite

stolid after Bate’s more dramatic course. Sometimes you may choose to

hear the piece as a brilliant toccata firmly within the French tradition;

at others you may want to sense its reaching towards a more mystical,

modern way of translating religious sensibility into music. I can only

suggest you hear both.

If my taste inclines towards Latry in Nativité,

it swings to Bate in Les Corps Glorieux ((1939), principally

for her smoother narrative flow and surer handling of that work’s pivotal

movement, Combat de la Mort et de la Vie. As in La Verbe,

a fast, minatory opening section builds up tension, which is then cut

short and slowly dissipated by a long, luminous meditation. Latry’s

grandeur spills over into grandiosity as his leisurely tempo loses the

work’s pulse. This seems pretty crucial to me if for no other reason

than that its composer was so fanatical about a feeling for rhythm,

to be observed both in his works and his coaching of performers. His

own tempo for La Verbe is almost as slow as Latry’s, but the

pulse never disappears. Bate refuses to succumb to the meditation’s

possibilities for somnolence and the result seems to move and yet stand

still in just the right way. Likewise, the long phrases of ‘Prière

du Christ montant à son Père’ which concludes l’Ascension

(1933/4) must convey the sense of Christ, as it were, rising rather

than hovering tantalisingly in mid-air. Both Latry and (unexpectedly)

Boulez (in the work’s orchestral version) misjudge this while Bate’s

purposeful phrases spin effortlessly towards their inevitably serene

conclusion. (If you want to hear Christ not so much rising as zooming

towards his father, try Stokowski on Cala. Shockingly ardent: Messiaen

was reportedly and unsurprisingly disapproving).

Apparition de l’Eglise Eternelle (1932) has

the pulse written into the fabric of the movement, and with its ‘Très

lent’ indication this startling answer to Debussy’s La Cathédrale

Engloutie holds less possibility for getting it ‘wrong’. Bate and

Latry both grade the crescendo nicely and (more difficult) return to

the work’s original, gloomy piano at the end without too many clunky

registral changes. I happen to prefer Gillian Weir’s more legato phrasing

at the work’s C major midpoint; Latry is quite choppy here and whatever

Bate did is rounded away by the cavernous Beauvais acoustic.

In many ways, this is the nub of the matter. I could

compare individual movements until my keyboard cried for mercy, but

the very instrument used and the acoustic surrounding it do, in this

case, play a huge part in deciding preferences, especially when the

playing is so confident and (largely) accurate in both cases. Bate’s

Beauvais recordings were well known, when they originally appeared,

for their huge resonance and dynamic range (my LP player wasn’t having

any of Bate’s Dieu parmi nous, scored deeply into the vinyl,

and let me know this with hideous skippings and scrapings) and while

this redounded greatly to the recording producer Bob Auger’s credit,

I found myself wondering just how many notes I could discern amid the

Danien-Gonzalez clamour. CD remastering has improved matters, but I

still find listening to stretches of fast music on the Bate set frustrating

because of the lack of clarity. Les yeux dans les roues from

Livre d’Orgue is another toccata form but a world away from the

splendour of its formal forebears. The page is black with notes, and

the Isaiah quotation which precedes it makes clear that the piece should

engender a sense of breathless terror. Bate fails in this, not through

lack of virtuosity but simply because you can’t make out what’s going

on. The contrast with Latry couldn’t be clearer, especially as their

tempos are identical (the extra three seconds on Bate’s recording can

be attributed to the echo!). DG’s recording team in Notre Dame used

an unprecedented twelve microphones and must have spent an inordinate

length of time at the mixing desks, but their efforts have produced

a true sonic spectacular, full of depth and delicacy. It bears only

a resemblance to the Cavaillé-Coll instrument you hear when visiting

Notre Dame, as there is no place in the building from which you can

hear all the ranks with the transparency achieved here, but it reveals

the harmonic and rhythmic complexities of Messiaen’s music to a degree

only previously realised by the Collins’ engineers for Gillian Weir.

That was on a very different instrument (a Frobenius) in a very different

and much less resonant acoustic (Arhus cathedral) which gives much more

‘help’ to the engineers while reducing the perfume available to performers.

The Danien-Gonzalez in Beauvais naturally has more of that French perfume

(heart-melting voix célestes in the Prière après

la Communion from Livre du Saint-Sacrament) as well as a

pedal bassoon of impressive strength and quick response: the low Cs

which form the firmament of Apparition’s climax are just as clear

for Bate as they are for Latry, though one senses that the DG engineers

have done some tweaking to make it so.

The agility of the instrument’s response to the player

becomes even more vital in the middle-period works, when page after

page of abrupt registral changes and lightning-quick birdsong demand

fabulous virtuosity from both. Messe de la Pentecôte and

Livre d’Orgue form with the orchestral Chronochromie a

triptych of works central to Messiaen’s life, chronologically and musically.

They are his boldest and most imposing, containing few points of repose

or hooks on which an unfamiliar listener may hang an ear. By that same

token they also offer richer rewards to the adventurous listener than

almost anything else in Messiaen. The premiere of Livre d’Orgue

almost didn’t happen, so great was the crush of people trying to squeeze

into the church in Stuttgart where Pierre Boulez had organised the concert.

Messiaen was unable to enter the church himself and had to find a side-door:

I wonder if the cycle will see similar enthusiasm ever again? Though

Latry and Bate take roughly the same time over both the Messe

and the Livre, I frequently found that Bate felt quicker because

she doesn’t articulate as clearly as Latry. Sometimes, as in the

Pièces en Trio of the Livre, it’s a matter of taking

the bizarre leaps and note values and apparent disjunction's at face

value and playing them absolutely straight, as Latry does. Sometimes,

as in the Tongues of Fire introit in the Messe, it’s a matter

of choosing varied enough registration that will make the different

lines stand out from each other (Thomas Trotter is particularly successful

at this in the Messe, helped by a forward Decca recording at the Cavaillé-Coll

of St Pierre de Douai). Like Soixante-quatre Durées which

ends the Livre, the short Verset pour la Fete de la Dédicace

may never yield up its enigmas to me; I simply enjoy the noises it makes,

and I enjoy Latry’s noises more than any other version, because he seems

to trust Messiaen the most.

The pendulum that has been swinging in terms of the

two players’ approach to the oeuvre is now past the midpoint, and it

is Bate who consistently takes more time in the two ‘late’ cycles, Méditations

sur le mystère de la Sainte Trinité (1969) and

Livre du Saint Sacrement. The Meditations feature (or seem

to) more birdsong than any other work (four of the nine movements end

with the plaintive song of the yellowhammer) and I find Latry more consistently

effective at giving wing (sorry) to what look on the page like endless

streams of unpredictable note clusters and phrasing them in a realistically

avian way. Notre Dame also offers more colours on the manual stops with

which he can distinguish the many different species featured. Bate scores

in the work’s sections of Gregorian chant, like the opening of no.2,

Dieu est Saint, where a spacious tempo feels essential for creating

the right sense of majesty: if I were singing the chants at the speeds

Latry sets I’d feel rushed, and he sometimes sounds as if he is embarrassed

by their inclusion. However Latry is far more relaxed (3’55" to

Bate’s 2’38") in no.3, La Relation réele en Dieu est

réellement identique a l’essence, which enables him to unravel

the convoluted three-voice counterpoint as though nothing could be easier

to play or to listen to.

Bate gave the premiere of Livre du Saint Sacrement

(the only organ work for which the composer did not do this for himself)

and her subsequent recording, the work’s first, lasts almost 130 minutes.

Hans-Ola Ericsson was also coached extensively by Messiaen in this work

and his two recordings (on Jade and BIS) take around two hours, suggesting

that he preferred spacious performances. Latry takes a little over 100

and rarely feels rushed and most performers in the last ten years have

agreed with him (Gillian Weir, Stephen Cleobury and Anne Page among

others). In these last two mighty cycles Messiaen adds to his compositional

armoury the technique of a langage communicable, whereby theological

concepts (and sometimes whole tracts of Aquinas) are literally spelt

out in the music using a system of notation. Important words like Dieu

are assigned their own phrase; all the letters of the alphabet are given

a pitch, duration, dynamic and registration. To say that this results

in composing by numbers would be grossly simplistic, but I think there

are legitimate concerns about the way that the composer used various

techniques or ‘found’ musical objects (the langage communicable,

birdsong, indian rhythms, plainsong) to, as it were, do a lot of the

creative work for him. Messiaen himself talked of the Livre du Saint

Sacrement as a summation of the experience he had gained from improvising

every Sunday at the Eglise de la Saint-Trinité where he was organist

for over 60 years until shortly before his death. This sense of taking

what was appropriate (the Gospel for the day, a bird he had recently

heard) and bending it to his uses with a carefully honed musical language

is a skill in itself, but it becomes more and more apparent in the works

he wrote after the completion of the monumental Saint François

d’Assise in 1982. He worried he would never compose again – and

yet the two hours of Livre were put together in a matter of months.

Whether Messiaen approved or not, the large-scale set

pieces which form the pillars of the cycle have a narrative that is

more evident in Latry’s (and Weir’s) recording. Even the obviously meditative

movements like Institution de la Eucharistie don’t need the time

that Bate lavishes upon them, though hers is a beautiful achievement

in its own right and benefits enormously from being recorded not in

Beauvais but in Saint-Trinité itself. Bate certainly makes something

gloriously imposing of the sequence of rainbow coloured chords which

flash across the keyboard in La Resurrection, but Latry discovers a

more impetuous joy with shorter phrase lengths.

If a further reason were needed to recommend Latry

above Bate, and indeed above the rest of the competition, it can be

found in his inclusion of two pieces only recently published and previously

unheard since their composition in the early 30s; and the Monodie

of 1963. None of these short works says anything not expressed elsewhere,

but the Offrande au Saint Sacrement is attractive and would make

a convenient standby for an organist when leafing through the library

for communion music. Newcomers to this body of music may fight shy of

committing themselves to the outlay required for Latry, and they will

gain many hours of pleasure and unfailingly sensitive playing from Jennifer

Bate. Those who invest in Olivier Latry’s set will gain all that plus

the thrill of the vivid recording and his dramatic instincts. This sets

the standard.

Peter Quantrill