Florence Foster Jenkins has something like cult

status among those who revere her wartime recordings. When I was a student

her performance of the Valentine Aria would often be played at

the close of a dinner party in the hope it might inspire us. For very

few did it actually inspire anything. Like the port throwing that went

on at the monthly meetings of the Hilaire Belloc Society it was always,

I thought, a wasted opportunity. What better way could there be to seduce

a beautiful young woman (or man, for that matter) than to be inspired

by one of the most extraordinary soprano voices in history?

Listeners familiar with either the LP or the RCA disc

of Florence Foster Jenkins singing Mozart (which includes a hell

raising Queen of the Night Aria) and lesser songs will know what I mean;

for those who have never encountered this phenomenon (no other word

quite sums up the mystery of her appeal) then you are in for a treat.

Here, in its own peculiar way, is a voice as memorable as any to have

made its way onto record.

Foster Jenkins famously avoided public concerts, preferring

instead to give recitals to a select few at the Ritz-Carlton in New

York, and only then on an annual basis. Tickets were rumoured to be

amongst the most sought after in the city, partly inspired by a critical

backlash which left musical commentators struggling to find words adequate

to describe the experience to which they were unwitting witnesses. A

taxicab crash in 1943 left her with the ability to sing a "higher

F than ever before". It was never established at the time whether

the attempts to curtail her career were deliberate or accidental, but

rather than sue she instead sent a box of cigars to the company. An

increase in her pitch, she thought, was priceless and deserved payment

in the kindest way possible. In 1944 she made her debut at Carnegie

Hall (sold out, of course) and promptly died exactly a month later.

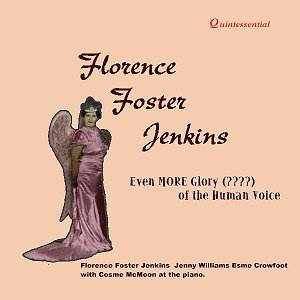

It is fitting that this newly discovered disc (coming

from private archive recordings made during the height of the Second

World War) of some of the greatest music for the soprano voice ever

written includes Verdi. Her Verdi Club was something of an extravaganza

and a particular passion of the ageing diva, and always it seems a scene

of lavishness befitting any Queen of the Nile. There is, perhaps regrettably,

no Aida on this disc, but we do have one of Verdi’s most searing

arias, Pace Pace! Searing is not the quite the right word to

use in describing Foster Jenkins’ performance of it here since the voice

never quite reaches a top C at the close of the aria. Dimenuendos are

a shade of heavy black at the opening (more dirge-like than evocative

of peace), and the serenity of the high notes is more reminiscent of

a shrieking lark than the human voice, albeit one of a 70 plus year

old soprano. It is certainly a full blooded reading, as appetising as

Steak Tartar on a winter’s day. The Willow Song is bleak indeed, the

most monotonic performance I have ever encountered. What should drip

in colour here sags like peeling paint. Verdi originally thought the

aria should produce three voices from the soprano; with Foster Jenkins

we get not a single voice but a thousand cracked notes.

Turn to Wagner and you might think we are in more natural

territory. Foster Jenkins at least probably looked the part (she had

a Wagnerian ugliness, a Valkyrian demeanour) but Isolde’s Transfiguration

is somehow massacred. Had she ever had the ability to sing the role

on stage her Tristan would long ago have died before we ever reached

the Liebestod. As it is, the Liebestod sees Isolde singing of spiritual

union and she dies herself experiencing it in glorious song. In Foster

Jenkins’ reading we have to forget the great recordings of the past

by Flägstad and others and instead think of something more earthbound

(almost subterranean). The voice never convincingly rises much above

the stave, and where notes should be floated they have a gale force

choppiness. The voice rises and falls like a millennium of empires,

and with as much noise and bloodshed it should be said. Lines such as

‘in mich dringet, auf sich schwinget’ crack as loudly as the splitting

hull of the Titanic.

But I have left the best until last – a reading of

the Trio from Der Rosenkavalier with one of Foster Jenkins’ regular

recitalists Jenny Williams and the by then almost unknown cabaret singer,

Esme Crowfoot, who was rumoured to have never recovered from the experience

of singing with Florence. One of the most sheerly beautiful and intense

of all opera excerpts the Trio is as sublime as it is possible to get

– think of Fleming, Graham and Bonney with the Vienna Philharmonic.

Hear this performance and things will never be the same again. Foster

Jenkins as the Marschallin is more akin to Field Marshall Kitchener

so hectoring is her tone. The music becomes a call to arms rather than

an elegy to lost love and the loss of time. The lyricism of the music

is disbanded in favour of something entirely inappropriate. Radiance

at the top of the register is replaced by ritual wailing, the warmth

of tone expected in the middle of the register is soaked in a wobbling

shrillness and the richness of tone below the stave is instead reminiscent

of thunder, with the occasional cannon-ball thrown in for good measure.

It is a travesty – even by the standards of Florence Foster Jenkins.

At the age of 76 Foster Jenkins is the oldest Marschallin

in history, but then neither her Isolde nor her Leonora are much younger,

and by today’s standards are decidedly geriatric. This disc is a timely

reminder of the sanctity of music; one wonders whether Charlotte Church,

once the voice has truly cracked from its rotten nut, will sound like

this. As this disc shows one Florence Foster Jenkins is quite enough.

Marc Bridle