Burrowing through the booklet, I chanced on the dreaded

word "serialism". On the instant, I switched from "booklet

burrowing" to "brow furrowing". Being a fan of the music

of Harry Partch, and therefore having singularly strong opinions about

the importance of tonality to the average set of human lug-holes, I

tend to (only "tend to", mind!) fight a bit shy of Dodecaphonism

(excuse me while I wash out my mouth with soap and water). But then,

at some point in my existence, I recall someone pointing out to me that

"Do - you-know-what" and Serialism are different animals,

and that you can be a Serial Composer without necessarily being, well,

one of those others. Into which camp does Lutoslawski

fall, I wondered (somewhat belatedly, having had his music in my record

collection for years)?

Well, as it happens, it’s not that simple! He only

got his compositional debut in by the skin of his teeth before the Second

World War got started. It is a curious fact that, having been taken

prisoner by the Nazis and having escaped, he didn’t make a beeline for

Switzerland or flee westwards, but returned to Warsaw where he teamed

up with Panufnik, performing "underground" recitals (presumably

for the "underground"?). After the war he was somewhat

constrained by the Stalinist regime, mostly to folk-song arrangements

and "nice" music for children - though this period also saw

the birth of his Concerto for Orchestra. It was only after Stalin

turned up his toes that Lutoslawski felt

free to flex his musical muscles.

Enter "serialism". But not for long. To be

a serialist you have to be a control freak, especially if you’re going

to keep up with them there "total serialists", who happened

also to be "you-know-whats”

and who produced music that was not only largely incomprehensible to

the average man in the street, but also (I suspect) fairly baffling

to the juries of their peers that probably made up most of their audiences.

Lutoslawski ducked. He decided to go in for aleatoricism

- the introduction of the element of chance, which was of course anathema

to dodecaphonic total serialists (ouch - mouth wash time again!), being

utterly incompatible with control-freakism.

The booklet note for this CD, a pretty enlightening

piece of prose by Richard Whitehouse, reminded me that from the mid-1970s

onwards there was "a new emphasis on melodic elaboration".

That means you should hear a distinct difference between the meat of

this CD - the Postludes and the Preludes and Fugue - and

the attendant course of occasional sweetmeats - the Mini-Overture,

Fanfares, and Prelude for GMSD. And, by ‘eck, you can!

Of course, the problem with aleatoric music is that you need to hear

several live performances before you can even begin to appreciate

what it’s about. Enshrined on a CD, aleatoricism suffers the ultimate

indignity, becoming indistinguishable from the old plain-Jane "play

the notes as written" music that the composer has sweated cobs

to break away from. Listening to a recording, you can only know that

chance is playing a part if you are told that it is!

Almost paradoxically aleatoricism,

even in Lutoslawski’s special “limited” version, by virtue of its inherent

tendency towards chaos can often result in the self-same feeling of

incomprehensibly dense argument produced by the control freaks. So,

am I about to kick Lutoslawski’s music into the rejects bin before I’ve

even commented on the CD in hand? You can bet your sweet life I’m not!

He has some superb redeeming features, not least of which must

be the same mathematical background that attracted him to the sense

of the statistical in music in the first place. This came, I reckon,

from the studies in mathematics at Warsaw University that he abandoned

in favour of studies in music at Warsaw Conservatory. The mathematically-minded,

even those of a statistical bent, have an overriding interest in making

things crystal-clear (hence, maybe, the difficulties he had with the

Postludes that Richard Whitehouse mentions).

Another feature is his interest, along with Ligeti

and Penderecki, in "texture" (another slant on "statistics").

The driving force here is the creation of fascinating sounds

as the central element of a composition. Fashioning fascinating forms

from musical marble may hardly be a recipe

for the greatest profundity, but the results can be immensely engaging

in that truly classical sense of “entertaining the intellect”. If you

couple that with Lutoslawski’s amazingly keen ear for musical “colour”

as we commonly understand it, there’s a lot to be said for this

angle - which lends a serious slant to Beecham’s (I think it was Beecham’s)

caustic comment about the English not liking music, but liking the noise

that it makes. Well, I rather do

like the noises that Lutoslawski’s music makes; I would guess

that (if he’s anything like on Arnold’s wavelength) that’s what matters

at rock bottom.

My first reaction to noting the performers was, "A-hah!

Polish performers playing Polish pieces - they should be well steeped

in the idiom". But then I remembered that this sort of reasoning

only really holds for music of an overtly nationalistic flavour. Shucks!

Never mind. Anyway, it doesn’t alter the question! What sort of a job

do they make of this music? Answer: not at all a bad one, as it happens.

Of the occasional pieces, the Mini Overture

for brass quintet is by far the longest - even at three minutes! Played

with cool relish and commendable light and shade, this jaunty little

number is quite closely recorded. Not to worry - that’s only a problem

for a few seconds - of "breathy" quiet trumpeting - just before

the smile-begetting little gesture that ends the piece.

At the other extreme, if I can call it that, is the

twenty-five seconds long Fanfare for CUBE

that Lutoslawski wrote for the brass quintet of Cambridge University,

by way of thanks for the honorary degree bestowed on him in 1987. For

Lutoslawski, it’s an alarmingly conventional gesture (hardly challenging

Brahms’ similarly-prompted Academic Festival Overture!),

dispatched with correspondingly conventional pomp. By way of contrast,

the twenty-eight seconds of the Fanfare for the University of Lancaster,

composed to mark a mere visit to a common-or-garden red-brick "uni",

employs a larger brass ensemble (plus snare-drum) with far more flair.

Or so it seems, until you hear the Fanfare for Louisville, which

is a veritable volcanic eruption of tumultuous roarings and shriekings,

blasted out with satisfyingly manic energy by the brass of the PNRSO.

The Prelude for GSMD (Guildhall School of Music

and Drama) is a laid-back orchestral andante, rolling amiably

along, accumulating faster-flowing overlays as it works its way almost

nonchalantly up to a final sonorous chord. In fact, as a prelude

it can sit quite nicely in front of the Three Postludes, should

you happen to feel like it.

Which brings us nicely to the meaty main courses, I

found the Three Postludes hugely enjoyable, though don’t ask

me why they’re called postludes - they don’t seem to come after anything

- except one another, which would anyway make the first one a prelude

(unless of course you adopt my suggestion from the previous paragraph)!

The first two feature some spectacular fusillades of antiphonally-arrayed

percussion. At the start of No. 1, the spacious ambience of the

recording is immediately apparent in the slowly rotating mists of hushed

strings, against which are set clusters of parti-coloured sparks. Layered

brass crescendi and pounding drums build a climax of towering menace,

which at its height disintegrates in a whirring cascade of strings,

leaving the original textures to fade slowly. No. 2 is a contrastedly

hyperactive prestissimo, fizzing around the orchestra like a

blustery snowstorm caught in headlights and - as if heard through a

windscreen - never penetrating much above a subdued mezzo-forte.

To my ears, it all seems to be played and recorded with a gratifying

combination of clarity and atmosphere. No. 3 is different again,

by turns vigorous, strident, muted, uneasy, its episodes are commanded

by a recurring, abrupt loud chord (something of a whip-cracking ringmaster).

Lashing all the "acts" into submission, this bully gradually

takes over the whole show before creeping off into the shadows. Read

into that what you will!

Lutoslawski, the note

informs me, explains in the score that the Preludes and Fugue

for 13 Solo Strings may be "performed whole or in various shortened

versions". Apparently, if the work is performed entire the sequence

of the preludes must be as written. If performed in an abridged version,

the order of the (selected) preludes is up to the performers, the composer

having craftily engineered their extremities to neatly dovetail together.

Guess what? I’ve tried it, and by golly it works! To be fair, it works

best if you copy the selection to MD, to eliminate the gaps where the

CD player is repositioning itself. Moreover, this explains why the track

divisions on the CD don’t seem to correspond to the points where the

continuity of the music sensibly changes (I’d have saved myself a lot

of puzzlement if I’d read the notes before I listened to the music!).

This is the one work on the disc where I felt that

the music could be better played, largely on account of my having an

old LP where this very music is better played (Warsaw Philharmonic

CO/Composer, Aurora AUR 5059). However, don’t be put off by that: this

is tough and challenging music for players as well as listeners, and

the 13 soli of the PNRSO make a more than creditable stab at it. Along

with the likes of Bartok, Penderecki and Ligeti,

Lutoslawski takes full advantage of the mind-boggling menu of timbre

and attack offered by the violin family, and this inevitably stretches

string players (as well as their strings!) to the limit.

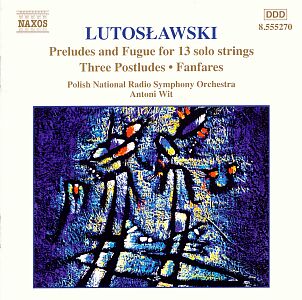

This disc is Volume 7 of Naxos’ cycle of the orchestral

works of Lutoslawski. Regardless of volumes 1 to 6, it constitutes a

pretty fair sample of the composer’s later music, both “serious” and

“occasional”, and a really decent introduction to anyone remotely interested

in the work of one of Poland’s “all-time greats". In this

context certainly, Antoni Wit and the PNRSO are admirable advocates.

They may not have the body and bloom of the top-flight "internationals",

but they make up for that (assuming that it’s even necessary) with bags

of character and enthusiasm.

Overall, and other than the minor quibbles I have otherwise

mentioned, the recording is very good. The brass pieces and the string

work combine warmth and brilliance by virtue of the ensembles being

placed forward on the "platform", but stopping short of sitting

in your lap. In the works for full orchestra, the acoustic is spacious

without muddying the waters. Moreover, the perspective is comfortingly

consistent, the smaller groups simply occupying the "soloists’

spot" in the same acoustic space as the full orchestra.

I will confess that I’d seen two reviews of this CD

before sitting down to write this one, but I’ve studiously ignored them

right down the line. However, one of them did suggest that the sound

was "quite studio-bound". As you can gather,

I don’t agree, any more than I can agree with another suggestion, that

the mature composer had perhaps misjudged the density of sound of which

13 solo strings are capable. If Lutoslawski erected an impenetrable

wall of noise, then I reckon that’s exactly what he meant to

do. Whether impenetrable or limpid, this CD provides some wonderful

sounds to savour.

Paul Serotsky