What is a mezzo-soprano? This is a question

which has occupied a good many of my thoughts over the past year or

so since an Italian soprano with whom I do much work changed teacher,

was diagnosed as a mezzo-soprano and is now blossoming vocally in a

way hitherto unimaginable. I have therefore witnessed the transformation

stage by stage. But what are the signs? How can you tell what a singer’s

real voice is?

I suppose I had vaguely presumed up till that time

that a mezzo-soprano was a soprano voice pitched about a third down,

but it doesn’t seem quite that simple. For one thing, the category hasn’t

always been recognised, at least not explicitly. In Mozart’s C minor

Mass, for example, there are parts for two sopranos (however, according

to the edition you have, one of them may be labelled "mezzo-soprano").

But the big solo for the lower of the two, while it descends to a low

A, is not suitable for all mezzo-sopranos since its coloratura passages

lie fairly high, and it is sometimes taken by a "normal" soprano

who can "manage" the lower notes. But an ability to "manage"

the lower notes does not necessarily turn a soprano into a mezzo-soprano,

for the part of Fiordiligi in Così fan Tutte also descends to

a low A. But elsewhere a lot of the role goes extremely high and it

has never been suggested that a mezzo-soprano might take it (well, recently

there have been hints that Cecilia Bartoli might do so, but she is a

special case; more of this later). There are also Mozartian parts which

go neither particularly high nor particularly low (Cherubino, Dorabella)

and which can be taken by either, and there are also some leading parts

(Oktavian in Rosenkavalier, Rosina in Barbiere, Carmen) which have been

taken by one or the other; the choice regards the tone-colour one wants

to hear in the part (in the case of Rosina some of the decorations change

according to which voice sings). So, while the actual label "mezzo-soprano"

seems not to date back very far, there has always been a recognition

by composers that voices all had their individuality and the strict

definitions "soprano" and "contralto" ignored the

reality that many singers were not wholly one or the other.

If you hear any female singer rehearsing, you will

realise that women have a faculty which men do not have. When they sing

a phrase over, not projecting the voice but to themselves, maybe to

check word underlay or intonation, they mostly sing an octave down,

at tenor pitch. Even a high soprano can get remarkably low when not

singing "in voice". This of course has no practical application

in classical music since the sound reaches no great distance (in light

music, with a microphone, the technique is actually cultivated). Then

they take a deep breath and project the music in their singing voice,

which usually means an octave up. If the singer is a contralto then

she might sing at the same pitch since she will have rich, natural tones

which take her down to a G or even an F with little need to employ her

"chest voice". Even a soprano can project her voice

on these low notes, but she will have to use exclusively her chest voice.

Singers of light music (those with what we call a "smoky"

lower register) use this technique extensively and actually learn to

carry their chest voice up quite high (think of Shirley Bassey, for

example). Classical singers will tell you this hurts their voice and

they avoid doing it. Occasionally you will hear a soprano doing what

sounds like a Marlene Dietrich imitation as a stunt, by and large, though,

a singer has to train as one or the other and any attempt to run parallel

careers only ends in grief.

But there is also a way of catching some of the chest

resonance to enrich the lower notes. If you listen to a singer like

Christa Ludwig you will hear that even as high as the F above middle

C she catches this resonance which then gives fullness to her timbre

as she descends to her lower notes. This is a very different matter

from the throaty roar which we hear from Risë Stevens in her recording

of Gluck’s Orfeo – the effect there is not of enrichment, for there

is nothing to enrich, it sounds merely worn out and jaded. So, setting

aside what is just unpleasant singing, if you compare a pure contralto

like Ferrier and a mezzo like Ludwig singing the same music, you will

hear two quite distinct timbres, two different kinds of richness, equally

beautiful.

That’s one end of the voice. Then there’s the question

of the passaggio, or break, between the middle and upper registers.

Again, you might think that a mezzo-soprano would have this about a

third below the soprano and the contralto lower still, but actually

it seems to be in roughly the same place for all women, around the F

on the top line of the stave. A contralto will probably stop here, a

light soprano will be as happy as a lark singing above it. Between these

extremes each singer finds the area where she is happiest, and also,

one hopes, that in which she can exhibit what is most individual in

her own timbre of voice. So a mezzo-soprano may have all the top notes

of a soprano, yet feel she is giving the best of herself in her middle

register. A light soprano could presumably develop her chest register

to descend as low as a mezzo, but will have chosen not to do so, probably

on the basis that her upper register is where she feels happiest and

where her voice appears to best advantage. There is at least some degree

of choice in the matter, since for psychological reasons a singer may

feel she is expressing herself best up on high or down in the depths.

And the voice itself may shift up or down with the passing of time.

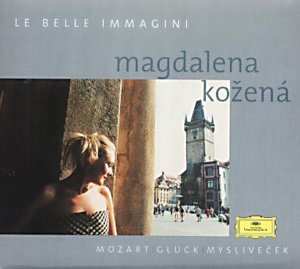

Magdalena Kozena – to get down to brass tacks at last – has told how

she used to sing Gluck’s Orfeo but now finds the role too low for her.

My query – which formed itself in my mind before I saw the interview

in question – is how long she is going to remain a mezzo-soprano at

all.

The test piece is the Lucio Silla aria. This goes down

to a low A, and she resolves it with a weakish chest-note. Any soprano

could manage this. The bulk of the aria is pretty high, with a top C

in the cadenza which does not seem to trouble her (but we don’t know

how easily she can hold this note for a long time). She seems entirely

happy – as she had already shown in Myslivicek’s Antigona aria – to

rattle off coloratura around and above her break. From her middle register

up to her highest notes her voice has a natural, fairly light, golden

sound. Her vibrato is, shall we say, inclined towards the maximum acceptable,

but for the moment it is a voice you can just sit back and drink in

for its own sake.

One pleasing aspect of mezzo-sopranos (whether they

really are that or not) is their willingness to look out new repertoire,

presumably a reflection of the fact that standard operatic pieces don’t

quite fit them. Recently Cecilia Bartoli had a tear-away success with

a disc of pre-reform Gluck (Decca 467 248-2 – see my review

of this). One of the Clemenza di Tito arias turns up again in Kozena’s

collection of fairly rare Mozart (a swift but actually rather gentle

"Voi che sapete" being the exception), rarer Gluck and even

rarer Myslivicek. The obvious point when comparing the two versions

of Gluck’s "Se mai senti spirarti" is that Bartoli sings it

a tone higher (so what was the original key?), carrying her up to a

high B which she resolves with celestial ease. Her tempo is also much

slower (involving considerable feats of breath control) and time seems

to stand still as her almost disembodied tones float languidly on the

orchestra. Kozena’s estimable version seems plain beside this. So if

Kozena is hardly a mezzo-soprano, what is Bartoli? Well, she could sing

as a soprano, but her lower register assumes a contralto-like richness,

which she can carry right down without undue use of chest tones. So

yes, I think she is a mezzo, if one with a rather exceptional range.

Leaving aside the technical questions, what matters

is that Kozena has a lovely, fresh-timbred voice, whether you regard

it as a mezzo or not. Her manner of interpretation is more straightforward

than Bartoli but her commitment is not in doubt. She does her compatriot

Myslivicek proud (Gluck was a compatriot too, of course). Mozart always

retains his special qualities but she makes out a case for Myslivicek

being on a level with the lesser-known works of Gluck: He emerges as

a little more traditional, more inclined to take at face value the florid

traditions of opera as he found it, while Gluck moved towards reforming

them. There is a bitterness in the text of "Dunque Licida ingrato"

which I don’t find in the music (and I don’t think this is any failing

of Kozena’s) but the music is otherwise vital, soundly composed, never

banal and a fine vehicle for the voice. With good support from orchestra

and conductor this is a disc which should be bought even by those who

resist hype on principle.

From a mezzo-soprano who may not be a mezzo-soprano

I next move to the other end of the scale to consider the case of a

singer who is billed as a mezzo-contralto, Rebecca De Pont Davies (Fleurs

Jetées: Songs by French Women Composers, LORELT LNT109: to

be reviewed shortly).

Christopher Howell