This disc will come as somewhat of a culture shock

to those who, like myself, have only previously encountered Theodorakis,

Zorba's Dance aside, in his rather overblown Ode to Zeus,

on John Williams' (the film composer) 1996 Olympic disc, nestling alongside

(and completely outshone by!) Michael Torke's glorious Javelin,

and in miniatures championed by the likes of John Williams (the Australian

guitarist) and Sharon Isbin.

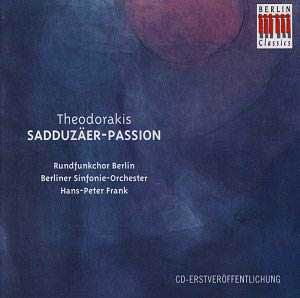

In complete contrast, Sadduzäer-Passion

is a complex allegorical work, based ostensibly on the history of the

ancient Jewish sect but written as an elegy to the Greek political left,

in which Theodorakis was heavily involved (and subsequently jailed for)

around the time of the "Colonelsí Coup". It is also sung in German (no

translations included) though based on the words of his friend Michalis

Katsaros.

Anyway, what about the music, you are probably asking.

If it is a masterpiece, and at least two of its seven sections at least

approximate to that description, then it is probably a flawed one, as

is the performance, if only by the nature of it being a live take, pops,

clicks and all (it has been digitally remastered however). One of the

main reservations, and one that would strike the casual or uncommitted

listener immediately, is the (excessively?) forceful delivery of the

speaker whose recitation has unnerving echoes, given the language, of

the Nuremberg rallies (maybe this was what Theodorakis intended, given

the subject matter). Still, the music is, without exception, interesting

and often very moving, and reminds me, variously, of Wagner (unsurprisingly),

Lili Boulanger, Koechlin (Law of the Jungle), Berg, the Ropartz

of St. Nicolas and the Martinů

of The Epic of Gilgamesh (even, in places, of Messiaen

or the recent work of someone like Haukur Tomasson). Despite this the

piece holds together very well as a whole and I am probably doing Theodorakis

a disservice by implying that it is so polystylistic, because it actually

isn't!

The first section, Form meines Ego (Form of

my Ego), is upbeat and fairly light in mood, lulling you into

a sense of false security, quickly dispersed by the almost Bergian angst

of the first part of the second movement Blinde Zeit (Blind Time).

The heart of the piece is, at least to my mind, located in the fifth

and sixth sections (Im Toten Wald and Blonder Jüngling),

where Theodorakis's Greek roots are displayed to their full in some

wonderfully potent, archaic modality (the only direct parallels I can

recollect are in some of the movements of John Foulds' brilliant Hellas

suite and, maybe, in something like Pour les Funérailles d'un

Soldat by the aforementioned Lili Boulanger). The finale starts

off promisingly and, despite a long (overlong?) section with the speaker

to the fore, ends with a remarkably powerful climax, a transfiguration

of the insistent percussive and vocal rhythms of the germinative first

movement into something more sinister, "a warning for the future" as

the highly informative booklet notes would have it.

This score continues to fascinate me and I would recommend

anyone at all interested in twentieth century music to hear it at least

once. The recording is not flawless but the intensity of feeling, conveyed

across 19 years, via CD, from this performance, remains undiminished.

As much as I love the English pastoral and American "outdoor" traditions,

a work like this demands to be heard and, in my case, reheard, irrespective

of its independence from those or any other obvious idioms.

Neil Horner

![]() See

what else is on offer

See

what else is on offer