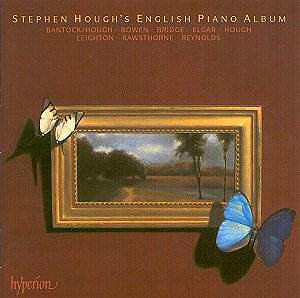

Stephen Hough is one of our finest pianists. He has

an extensive repertoire embracing much that is outside the well-trodden

paths of many recitalists. Unlike so many performers these days – on

whatever instrument – he also tries his hand at composing (and arranging)

for his instrument.

This very attractive Hyperion release is representative

of his skills and is of especial interest to lovers of British music.

Few of the items thereon will be widely known, apart from Alan Rawsthorne’s

Bagatelles, which express so much in such a brief compass, and

the colourful and thoroughly characteristic In Smyrna which has

been swept up in the Elgarian revival of the past 40 years. (It may

be more popular now than in Elgar’s lifetime). The gossamer–like Bridge

miniatures are post–1918 but are in his pre-Great War lighter vein which

yielded so much for our delight.

York Bowen’s large output may work against his popularity

as it does in the case of others among music’s big producers. I had

previously heard none of these three pieces which form a rewardingly

varied group: Reverie d’Amour’s lushness contrasting well with

the wistful Serious Dance and the happy-sounding, if restrained,

Way to Polden (Polden is thought to be in Somerset).

Stephen Reynolds, born in 1947, is a new name to me

as a composer (he has achieved distinction as a pianist). These four

Poems are lighter interludes in a more "serious" compositional

output. Delius and Fauré are two of his favourite composers and

the Poems are attempts to write in their respective styles. I

could detect little that was Delian in the brief and charming Rustic

Idyll but considerably more in the much longer Serenade and Dance

of Spring. The Fauré Poems are most enjoyable, too,

their fluency arguing that Fauré the song composer was their

primary influence.

Mr Hough figures as a composer in the Valses Enigmatiques,

enchantingly light in texture and apparently full of personal allusions’

which (like Elgar’s Enigma Variations) need not concern the average

listener. I liked, too, his sensitive and affectionate arrangement of

Bantocks Song to the Seals.

Most of this repertoire can reasonably be dubbed light

piano music, of which British composers have written a huge amount and

which I suspect has given enormous, if largely untold, pleasure down

the years. The exception is Kenneth Leighton’s Studies, which

are much more craggy and astringent than anything else here, but whose

rhythmic imaginations, culminating in a very rapid and excitingly percussive

finale, repay the closest listening. Their superb piano writing reminds

us that Leighton was a fine pianist. Mr Hough clearly values them highly

and this may well be the definitive performance.

Good recording; I am happy to recommend this disc strongly.

Philip Scowcroft

![]() See

what else is on offer

See

what else is on offer