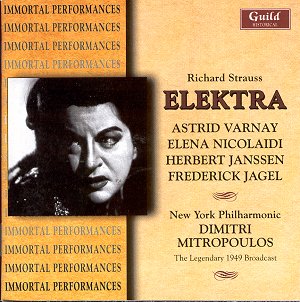

In the recorded history of Elektra, this set

would appear to represent something of a dream team, combining as it

does the talents of arguably the opera’s greatest protagonist and conductor

to date. Despite Birgit Nilsson’s subsequent ownership of the role for

a decade from the middle of the ’60s onwards many still regard Astrid

Varnay as the ultimate Elektra. This is with good reason, to judge from

the several recordings left to us: under Reiner in 1952, Richard Kraus

in 1953, William Steinberg in 1956 and Herbert von Karajan in 1964.

This set is now our earliest available documentation of Varnay in the

role, from a concert performance given on Christmas Day 15 years before

that Salzburg Festival appearance with Karajan. It’s worth noting the

technical infallibility and vocal stamina one would need to sing this

role over a period of 15 years, let alone to do so with such terrifying

confidence.

This broadcast is also the earliest account I know

of the score from Dmitri Mitropoulos; though I’m acquainted with performances

from Florence in 1951 (Anny Konetzni) and Vienna in 1957 (Inge Borkh),

I believe there to be several others. Messy ensemble for the opera’s

opening ‘Agamemnon’ motif doesn’t get the opera off to a promising start,

but Elektra’s opening monologue ‘Weh, ganz allein’ finds Varnay tempering

Mitropoulos’s tendency to press ahead with icily powerful blasts of

tone. This broadcast catches her in excellent voice, although in later

years her characterisation of the part would deepen. For Mitropoulos

too, impetuosity is the dominant feature here: the opening of Klytemnestra’s

scene is too fast for full menace to register. As Richard Caniell points

out in some notes that are nothing if not personal (‘the legendary 1949

broadcast… Varnay has never sung better than this, before or since…

Orestes is the name of her sanity’ are some of the more debatable pronouncements)

Elena Nikolaidi does better than many Klytemnestras in actually singing

the part rather than spitting it. Irene Jessner gets around the notes

but doesn’t invest them with the womanly allure offered by Karita Mattila

(in recent memory) or Leonie Rysanek for Kraus. Mind you, she doesn’t

get much chance to make an impact. There is a pause after Klytemnestra’s

scene, possibly occasioned by the demands of the radio broadcast or

a Christmas Day audience. It resumes with Elektra catching sight of

the shadow in the doorway which is eventually revealed as Orest. Poor

Chrysothemis’s second scene therefore is entirely cut and with it that

creepy passage where Elektra casts an insinuating eye over her sister’s

voluptuous body, ripe for motherhood, as Chrysothemis laments the lack

of boyfriend material around the house of Atreus (can you blame them?).

The other parts are fair, nothing more, though it’s a pity Guild couldn’t

find out who half of them were.

The sound and playing under Kraus in studio conditions

remain preferable. The WDR orchestra sounds far more amenable to the

score’s extravagant demands than the reportedly recalcitrant New York

Philharmonic, which in any case never took to Mitropoulos’s driven intensity.

Varnay doesn’t quite go for broke on her opening entry as she did in

1949, but she builds the role with a slow-burning vengefulness that

reaches its peak as Elektra scrabbles in the ground for the axe which

Orest will use to murder their mother. She frequently seems to enjoy

and benefit from Kraus’s more measured tempos with greater accuracy

of intonation and more surely drawn phrases. But no one quite pulls

the score round like Mitropoulos. Despite the fast tempos, his knowledge

of the score pays dividends at moments of otherwise bewildering complexity

like the arrival and departure of Klytemnestra where he is unmatched

at drawing out the music’s strands. He can also stretch the big moments

to realise perfectly the score’s unsettling combination (often simultaneous)

of lyricism and violence, notably at the gloriously OTT conclusion,

as Elektra dances herself to death. The Vienna performance from 1957

finds Mitropoulos in far more contemplative mood, dwelling on phrases

more and spotlighting motifs from within the orchestra. If only the

sound were not so crumbly this would be far more recommendable. The

Florence version is likewise sonically inferior, though the faults are

quite different; where the voices veer in and out of recession in Vienna,

the Florence version is in a disconcertingly vivid electronic stereo,

the focus of which wanders across the sound stage and makes me feel

seasick when listening on headphones. This is a pity, because the orchestra

is again extremely incisive and gutsy. Konetzni’s overcooked Elektra

also disappoints.

The bonuses on Guild (Varnay in Senta’s ballad, bits

and bobs from Boccanegra, Ballo and Herodiade inter alia) and Gala (substantial

chunks of an Act I of Rosenkavalier with Varnay as the Marschallin from

the Met with Reiner in 1953) are both appealing. Richard Tucker and

Leonard Warren partner her in the two extracts from Act I of Boccanegra

to especially thrilling effect, (and Weber’s Ozean, du Ungeheuer receives

as full-on a performance as I’ve ever heard). If a partial version of

Elektra doesn’t bother you, this set certainly offers a white-knuckle

90 minutes and a valuable chance to hear Varnay in full flight.

Peter Quantrill

See also review by Robert

Farr and Calvin Goodwin