Potential buyers beware: these two issues may not be

exactly as they seem. The two disc set listed above is an extensive,

largely chronological survey of Scriabin’s solo piano music, including

two of the sonatas and with the addition of the early Piano Concerto,

whereas the single disc issue, as a glance at the contents will show,

is identical to the second disc of the two disc set, though with one

work less, the 2 Pièces, op. 59. In addition, it seems to be

the same recital as one issued on the Etcetera label in 1992. So if

you buy the two-disc set – and I most strongly advise you to do so –

check first to make sure you don’t have most of the second disc in your

collection already.

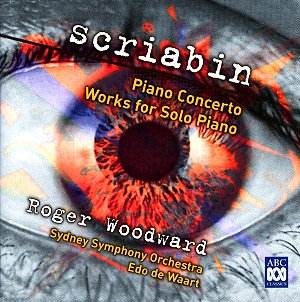

For many years Roger Woodward’s name was almost entirely

associated with the avant-garde, having had works composed especially

for him by many of the biggest names in twentieth-century music. But

his sympathies were always much wider than that, and it’s interesting,

after a long period when we didn’t hear much of him in Europe, to encounter

him now in Scriabin, and to note that he is just as successful in the

composer’s most youthful works as in the somewhat impenetrable music

of his maturity.

When talking about Scriabin, of course, maturity is

only a relative term: he died in 1915 at the age of only forty-three.

He composed extensively for orchestra and a large collection of piano

music, but virtually nothing for voices. This fascinating two disc set

allows us to trace his development as a composer. The very first piece

on the set, the first of 3 Pièces op. 2, is an affecting Etude

in C sharp minor, music whose sombre colours are all the more surprising

from a composer of only fifteen. The second, a Prélude, gives

a taste of things to come in its extreme brevity: at forty-five seconds

it is not the shortest piece on these two discs. The third is an Impromptu

whose melodic and harmonic style as well as the nature of the left hand

accompaniment could almost have been lifted from a page of Chopin. Several

of the earlier pieces show the influence of Tchaikovsky, and in the

more virtuoso pieces, of Liszt. There could scarcely be a greater contrast

between this music and the music from the end of the composer’s life.

From the early 1900s he began to be interested in matters divine and

mystic, and as these preoccupations found their way into the music so

the music became less immediately accessible, less melodic, and above

all, more chromatic and distant from traditional tonality. He began

to view the music he composed in the later years of his life as a sort

of preparation for some huge project which would bring together his

religious, mystic and musical philosophies. His death intervened, and

we can never know how his very particular thinking might have developed,

nor to what conclusions, musical or otherwise, he might eventually have

been led by it all. The music of this period is characterised by new

harmonies, often based on the interval of the fourth, and particular

"mystic" chords became associated with him. Whole pieces,

albeit short ones, might be based on a single chord and whatever melodic

strands he could pull from it. There is a kind of decadent richness

about this music, a kind of overstuffed impressionism, sometimes cloying,

claustrophobic, yet very compelling. Vers la flamme is typical

of this period as is the Tenth Sonata, sombre and lugubrious at one

moment, burning with a kind of diabolical energy at another.

The Piano Concerto was Scriabin’s first orchestral

score, and is most fascinatingly placed here in its chronological position

within the context of the solo works. It is a most beautiful and satisfying

piece. The first movement almost totally avoids any kind of bravura

display and is delicate and even reticent by turns, not at all what

we expect if we know only the later composer. The second movement is

a charming set of variations, and though the finale does contain a lot

of extremely taxing material for the soloist, there is no virtuosity

for its own sake. The end of this work, which has echoes of Rachmaninov

almost throughout, is most original and arresting.

No praise is too high for Roger Woodward’s playing

of this repertoire. He is fully equal to all the technical demands and

seems to have perfectly assimilated the composer’s complex, oblique

personality into his own. He is equally at home in the simpler expressive

world of the early works as he is in the later, more contemplative ones.

And where fire is called for he has it in plenty. More difficult to

define is his understanding of the architecture of this sometimes rather

diffuse music. He succeeds in making of each of the tiny little pieces

a significant and coherent whole, a complete statement in spite of the

brevity, and the longer structures hang together most convincingly in

his hands. He is ably supported in the concerto by the Sydney Symphony

Orchestra under Edo de Waart.

The Concerto was recorded in a different venue from

the rest and the recording dates vary between 1991 and 1999. The collection

is so well presented in its two disc format, however, that we are not

aware of its slightly piecemeal origins. I think most people are unlikely

to sit down and listen to the whole collection in one go – indeed, so

troubling is some of this music I think they would be ill advised to

do so – and so they won’t be perturbed by any changes in acoustic quality.

There are excellent notes, exactly what this music needs, by Ralph Lane

for the earlier music and Richard Toop for the later works.

Given the nature of the issue comparisons are not really

appropriate, but Konstantin Scherbakov on Naxos delivers a reading of

the Piano Concerto which is almost as poised and poetically charged

as Woodward’s and is coupled with Prometheus and a collection

of solo pieces. This would make a good buy for those who don’t want

to stretch to two discs, or you could opt for the single disc under

discussion here, but then you wouldn’t get the concerto, which would

be a real pity. Anyone seriously interested in investigating Scriabin’s

piano music couldn’t do better than invest in Roger Woodward’s marvellous

two disc set.

William Hedley