Let me say right away that that reviewing the first batch of

three discs in the Somm New Horizons series has been a real pleasure.

Like EMI Classics with their Début series and Harmonia Mundi

with Les Nouveaux Interprètes, Somm are providing a forum

for new talent, young musicians whose stature is already proven but who

are still close to the beginning of their careers. Itís a more than worthwhile

exercise, as these three discs prove, as do many of the EMI and Harmonia

Mundi issues also. These are marvellous musicians who, as is the way nowadays,

have nothing to fear from their elders from the technical point of view,

and in most cases possess an extraordinary maturity and musical insight

to go with it.

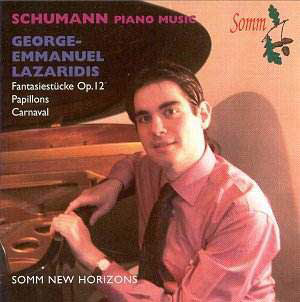

The Greek pianist George-Emmanuel Lazaridis is in his

early twenties and has studied extensively in London, notably at the

Royal College of Music, as well as with some of the most eminent pianists

such as Alfred Brendel. He is also a composer with many performances

and several commissions to his credit. The disc under review seems to

be his first commercial recording.

I imagine that the chief problem in launching a series

such as this is persuading the public to buy the discs when so much

material is available played by the giants of the past. How can a young

musician hope to compete? One approach is by judicious choice of repertoire.

For her superb disc on Les Nouveaux Interprètes the cellist

Emmanuelle Bertrand chose a programme of unaccompanied twentieth century

cello music, including works written specially for her, and thus there

is no reason to compare her playing to anyone elseís. George-Emmanuel

Lazaridis has chosen another path here: his recital of early Schumann

works is core repertoire, bringing him into direct comparison with some

of the greatest pianists of modern times. Whether there is any point

in comparing his Schumann to that of Rubinstein or Arrau, Brendel, Barenboim

or Ashkenazy, is another matter. I think people will do so, all the

same, which will be a pity, because the fact is that taken in its own

terms this is most satisfying playing, and I donít see how anyone buying

this disc could be disappointed.

Joseph Weingarten, writing about the interpretation

of Schumannís piano music, says that "early compositions such asÖPapillons,

CarnavalÖare all a series of miniatures strung together like

beads on a necklace to form a single chain". The difficulty of

interpreting such works lies in the fact that each single piece, short

though it is, is at once complete in itself and part of the larger structure

into which it must be convincingly integrated. This is certainly the

case in Papillons, where some of the pieces are very short indeed,

but even more so in Carnaval, a kaleidoscope of mood, feeling,

even scene or portrait painting, and often with literary references

thrown in. The work is inspired by a love affair: Schumann, only twenty-four

himself, had fallen in love with a girl several years his junior. She

came from the town of Asch, and much of the musical material of Carnaval

is based on the four notes Ė in their German form Ė whose letters make

up the townís name. An incurable romantic, one might say. The eight

pieces which make up the Fantasiestücke tend to be slightly

longer and more self-contained, and betraying in their character the

personal and musical maturity of the slightly older composer. Yet these

pieces too are strongly associated with, and dedicated to, a lady, though

yet another, Clara, later to become his wife, also figures in the complex

picture.

Lazaridisís view of Schumannís music tends more toward

the impulsive than the reflective. Listening to older pianists, Rubinstein

in Carnaval, for instance, or Kempff in Papillons, underlines

this, and some might find this element missing from time to time. They

might also sense a certain absence of grandeur. This is not to suggest

that the gentler episodes are neglected. On the contrary, they are beautifully

executed, especially perhaps in the Fantasiestücke. But

this is all young manís music, after all, and I find Lazaridisís impulsive

but not impatient approach both convincing and true to the music. And

he rises magnificently to every technical challenge.

The piano is satisfyingly present in a warm but not

too reverberant church acoustic. There are good introductory notes by

Christopher Morley, and indeed the whole product is well presented.

Somm do their young artists proud.

I hadnít heard of George-Emmanuel Lazaridis before,

but heís certainly someone to watch out for. Anyone wanting this particular

combination of works shouldnít hesitate.

William Hedley