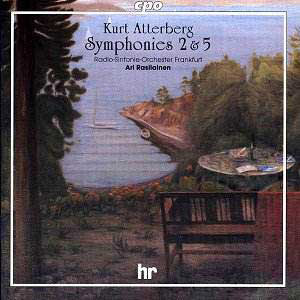

Ari Rasilainen’s impressive cycle of Atterberg symphonies continues

with these powerful readings of two of the composer’s most dramatic works.

Atterberg’s symphonies are immediately accessible, replete with strong

melodies and a language that appeals directly to the senses. As such it

is strange that his music is comparatively little known today particularly

since it was very popular in Germany and Sweden in the earlier decades

of the 20th century. Toscanini even championed his music with

his NBC Orchestra.

Atterberg’s substantial, 40-or-so-minute Symphony No.

2 was composed between 1911 and 1913. In its original form, as a two-movement

work, i.e. the first movement and another combining the slow movement

and scherzo, it was first performed in Gothenberg in 1912. In its revised

three-movement form, it was premiered in Sondershausen in July 1913.

It was performed by some of the leading conductors of the day including

Nikisch and Richard Strauss. A fast-flowing work in all three movements,

it is restless and heroic. One senses not only the turbulence of nature

but also of nationalistic ardour. There is a hint of Mahler but the

influence of Wagner is stronger: Tannhaüser and Siegfried

Idyll particularly reminiscent. Bax may come to mind too. There

is a touch of humour in the central movement and some material has its

origins in folk music.

The Fifth Symphony was composed between 1917 and 1922.

It was to prove highly successful in Germany such that it led to a contract

with the music publishers Breitkopf and Härtel who accepted three

of his symphonies. Possibly, in 1922, after the defeat of their aspirations

in the Great War, German audiences felt an empathy with the sentiments

of this rather darker tinged work? A German reviewer said it was, "…enveloped

in a dark-violet cloak over which black veils wave..." But this

is not a work full of gloom by any means, for here anxiety clashes with

angry defiance. Quiet, brooding and yearning is swept aside by music

that shakes an iron fist at fate. The central movement is elegiac and

has a melody that would have made Max Steiner jealous. But the most

interesting and the most substantial movement (at just over 15 minutes)

comes last. It includes remarkable use of dynamics, colour and shading.

It begins confidently with the music dashing forward. At one point,

there is material that is quasi-oriental. Then there is a starkly dramatic

passage for divided strings against brutal horn figures. Suddenly, the

music is overtaken by a grotesque sardonic waltz that suggests Teutonic

might rather than Ravelian subtlety. This tips over eventually into

resignation and a sad elegiac conclusion.

Virile, Late-Romantic music full of colour and excitement

given powerful, committed performances. Another jewel in Rasilainen’s

Atterberg symphonies cycle.

Ian Lace