In 1786 Mozart, hard at work on Le Nozze di Figaro,

took time off, without great enthusiasm, to write the music for a new

singspiel, Der Schauspieldirektor. The librettist was the same

who had provided the text for Die Entführung aus dem Serail,

Johann Gottlieb Stephanie the Younger, but this time the play was the

thing and Mozart’s music amounts to five pieces lasting, on their own,

little more than twenty minutes. Lack of enthusiasm for a project does

not seem to have acted as a block to Mozart’s inspiration – witness

the concertos for flute, an instrument he did not like – and these five

pieces, beginning with a well-worked out overture, have a good deal

more substance than the occasion strictly required.

Attempts have been made in the past to provide a minimum

narration to set the numbers in context (well, actually, in the mid-nineteenth

century someone tried to work it up as a full-scale opera with Mozart

himself among the characters); I daresay most people will be happy to

have just the music. The performance is a good one and the first recording

on original instruments. Listeners who are wary of these can be assured

that the Boston Baroque are beyond praise as regards tuning, nor do

they indulge in the exaggeratedly segmented phrasing some other period

groups go in for. In short, the pleasingly natural timbres of the instruments

can be enjoyed without any distractions, as can Pearlman’s vital but

not hard-driven interpretation.

The part for Madame Herz was intended for the same

singer as the Queen of the Night and calls for the same extended range.

Most of what Cyndia Sieden does is so splendidly confident as to raise

surprise – and the same comment applies to Sharon Baker too – when the

odd corner is awkwardly turned. Still, these moments are few, the small

male parts are well taken and in the last resort it is probably not

for this work that the disc will be bought.

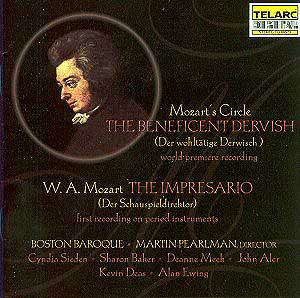

In 1998-9 the Boston Baroque hit the world headlines

with the first modern performance and recording of The Philosopher’s

Stone, a singspiel emanating from the circle of Emanuel Schikaneder

(the librettist of The Magic Flute) which was not unknown to

scholars, but for which evidence had recently come to light suggesting

that its anonymous composers included Mozart himself. No such evidence

– "no smoking gun" as Pearlman’s readable notes put it – has

been found regarding The Beneficent Dervish, but evidence has

been found that it was performed in March 1791, just before the composition

of The Magic Flute, rather than a couple of years after Mozart’s

death as had been previously believed. This obviously increases our

curiosity, making us want to check it out for possible influences on

Mozart’s masterpiece. And of course, one never knows …

Oh, but surely one does. Immortal, sublime Mozart!

How could we be for a moment in doubt? Or could we? All those wonderful

pieces that people listen to with tears in their eyes, swooning at their

spirituality, are you going to tell me that the same people would yawn

their way through the very same pieces if you told them the composer

was Salieri or his ilk? Or if you played them Salieri but fobbed it

off as Mozart, the waterworks would be turned on again? Or can we not

recognise the composer in some more objective way? For example, we are

told that cows produce more milk when they listen to Bach, so presumably

pieces of questionable authenticity could be put to the milk-yield test

(has anyone tried, though?) …

Well, joking apart, premonitions of The Magic Flute

mostly centre around a slightly Sarastro-like figure. To my ears, while

a lot of the music is in the lingua franca of Mozart’s Vienna

and does sound as if it could have been by him (but not by late

Mozart, surely?) there are also fairly frequent turns of phrase which

are distinctly un-Mozartian. All the same, and bearing in mind that

there is far less music in this singspiel than in The Magic Flute,

and also a much less serious subject, the music is usually a good deal

more than merely workmanlike and is well worth hearing. I was particularly

struck by the use of the piano in the orchestra in the second act, especially

in the Slave Women’s chorus. Did Beethoven know this and get some ideas

for his Choral Fantasy?

Again, the performance is mostly excellent. Alan Ewing’s

voice is not quite rich enough in its lower notes for the Dervish (this

would have been a part for Gottlob Frick, or even Boris Christoff) but

his singing as such is good and everyone else is fine.

The notes are in English and German, as is the libretto;

the translator had a lot of fun with the chorus "Vino pani".

"First-rate grubbo" for "Prima vesi" and "Muckymuck

you" for "Farscha tu" surely leave the originals standing.

The Impresario is well worth knowing and the

Dervish is quite interesting enough to strengthen, rather than

the reverse, the claims of the present version to be the preferred one.

Christopher Howell

![]() See

what else is on offer

See

what else is on offer