I recall an evening in Portofino, twelve or more

years ago, with an Italian colleague who – after having hosted a fine

dinner – cleared the dishes, introduced me to several species of grappa,

and proceeded to give me a history lesson that proved the Genoese had

discovered, invented or sold absolutely everything before anybody else

got there. As the evening wore on, and the level in the grappa bottle

fell, the paper tablecloth was covered in scribbled maps, family trees,

descriptions of voyages of discovery and proof of the fact that Genoese

banking families (including my host’s own!) had funded most of the wars

in Europe’s medieval history.

The image of that restaurant table returned, unbidden,

in stark relief as I started to read the plot line of Simon Boccanegra,

which takes place in fourteenth century Genoa. Vengeance, feuds, parental

rejection, a kidnapped love child, tragic death, vile poisonings, incitement

to murder foul, mistaken identity, startling truths revealed and deathbed

reconciliation; this plot is as intricate as any in the genre. And yet,

in many ways, it is atypical Verdi.

OK – at two and a half hours it’s about average in

length. And there are some good tunes in it – albeit less well known

than they deserve. But there are some significant aspects that set this

opera apart. Unusually for Verdi, it opens with an aria rather than

a chorus (unlike 19 of his total 26 operas), and it closes quietly,

almost with a whimper, rather than a great choral explosion. Further,

it is not a typically ‘Verdi tenor’ opera. The tenor in Boccanegra

is relegated to only a couple of arias and – though central to much

of the action, doesn’t really shine in a solo role. The star here is

the eponymous hero, initially privateer and later Doge of Genoa, in

what must be one of the most technically and dramatically demanding

baritone roles in the entire repertoire. Finally, this is where Verdi

meets Stanley Kubrick – the characterisation is intensely dark, sombre

and brooding – great introspection and angst, which is reflected in

the music.

As originally premiered in Venice in 1857, with a libretto

by Francesco Maria Piave, Simon Boccanegra was one of Verdi’s

few flops. It was a quarter century later, however, before the composer

– with the aid of Arrigo Boito – revised the opera completely, with

a new libretto and an entirely new Council Chamber scene. Since Verdi

was at this point at the pinnacle of his artistic abilities, the opera

benefits enormously from this revision (and it is the revised version

which is staged here and almost everywhere else today) and deserves

a better reputation than its early failure has left it with.

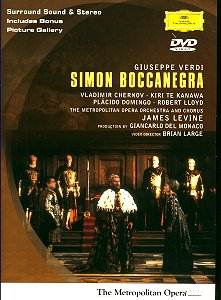

Perhaps the greatest complete recording on LP was the

Gobbi, Christoff, de los Angeles recording issued on Capitol, but I

can find no current CD issue of this, so the benchmark has to be the

Cappuccilli, Freni, Ghiaurov, Carreras 1977 recording under Abbado.

To compare a video presentation with a purely audio one is perhaps specious,

so I will limit comparisons to saying that I don’t think the Met production

comes up to the standard of the earlier one for pure performance characteristics,

but that the settings and production values contribute to an overall

very creditable and enjoyable production.

There are one or two instances in which the intrusion

of the video camera makes evident a hiatus that would probably escape

the live audience. Domingo, for example, spends a few moments transfixed

like a deer in headlights waiting for the chorus in the Council Chamber

to arrive at his cue and later in the second act is concentrating so

hard on injecting appropriate emotion into his singing that his lurching

progress across the stage takes on the character of a Quasimodo! Te

Kanawa also has a few momentary lapses, but overall the performances

are very fine. Of note, the tall, imposing Robert Lloyd as Fiesco demonstrates

why he is justly hailed as the greatest British bass of the late twentieth

century, giving a particularly powerful and stunning rendition of the

opera’s only reasonably well known aria, "il lacerato spirito".

But pride of place must go to Vladimir Chernov, who brings all the dark,

brooding introspection of Mussorgsky’s Godunov to Verdi’s music.

This is truly a stunning performance that should do much to bring this

lesser known work to wider prominence.

The staging at the Metropolitan Opera is quite brilliant.

The four separate sets are wonderfully constructed, the lighting evocative

and the costumes impressive, despite an anachronistic tendency towards

the high Renaissance rather than the mid-fourteenth century. Production

values that include a live fire in the hearth, a live falcon accompanying

Boccanegra’s first entry as Doge and a quite magnificent Council Chamber

setting, contribute to a fine recording. And in an era in which directorial

‘artistic license’ often changes the flow of what the composer probably

intended, this production is not interpretative at all, allowing the

viewer to focus on the music and the characterisation as it unfolds.

As a video production, this is a great example of what can (and, indeed,

in my view, what should) be done – no inappropriate angles, inexplicable

cutaways or interference with the performers for the sake of ‘the shot’.

The sound is very good throughout and the only minor complaint I have

is a lack of text in the notes, which would have added little to the

cost of their production, extensive as they already are.

Overall I loved every moment of the almost two and

a half hours of this recording. It appeals on many different levels

from the comic to the political. Verdi cannot resist inserting immensely

dramatic musical moments surrounding such phrases as "let my tomb

be the altar of Italian brotherhood", scarcely twenty years after

the Risorgimento. From the rounded beauty of the brief overture

to the quiet, contemplative ending, Simon Boccanegra is an opera

that deserves to be better known than it is and this video production

is one that could easily reach a deservedly wider audience, if well

promoted.

Tim Mahon